Friday August 30, 2024

The fundamental cause of Africa’s recurring crises and calamities are corrupt elites who transform cultural identities into divisive political wedges between communities.

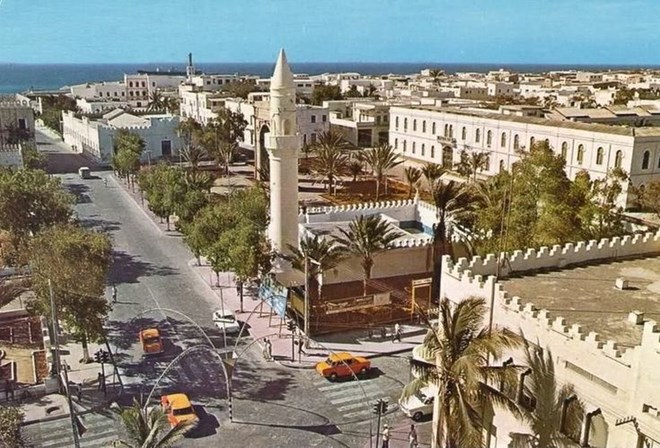

A nostalgic view of Mogadishu in its prime, reflecting the city's once-thriving urban landscape before the turmoil that reshaped Somalia's political and social fabric.

A nostalgic view of Mogadishu in its prime, reflecting the city's once-thriving urban landscape before the turmoil that reshaped Somalia's political and social fabric. Somalia had postcolonial Africa’s first democratic change of government in 1967 and enacted the first comprehensive civil service reform two years earlier. The late Zambian president, Dr Kenneth Kaunda, visited Somalia in 1968 and declared that “Somali democracy should be a model for other African countries”.

This remarkable progressive record did not last very long. A military dictatorship took over the reins of power in 1969. After nearly two decades of autocratic rule, the regime plunged the country into a vicious civil war from which it has yet to recover.

Somalia’s early success and the nature of its prolonged catastrophe have powerful political lessons for Africa. A discerning reader would ask: exactly what caused such a radical change of fortune and how can the rest of Africa avoid such a catastrophe?

The rise and fall of Somali democracy

There were two critical historical factors that shaped Somalia’s political journey and which it shares with many countries on the continent.

First, the Italian and British colonial regimes that ruled Somali territories turned a native’s cultural pedigree (male genealogy) into a political identity (political tribalism) in order to segregate Somalis into friendlies and terrorists.

Second, as a result of that strategy, the nationalist liberation movement was split into two groups: one that espoused civic-based liberation politics, while the other connived with the colonialists and harboured tribal-based political identity.

Fortunately, through mass mobilisation, the civic-minded parties won the struggle and led Somalia to independence. Meanwhile, the sectarians deployed tribal favouritism and corruption to gain power in democratic Somalia.

For the first seven years of independence (1960-67), the civic leaders of the republic remained faithful to the liberation ethos and the constitution. They enhanced the population’s civic commonalities by building the democratic foundation of the new nation.

State agencies had some of the lowest corruption on the continent during this time and children from all communities had equal but limited access to schools. Graduates from such schools competed fairly for job opportunities in the public service regardless of their genealogical background or region of origin.

In addition, people could move to any part of the country and settle there as equal citizens. Despite such progress in national integration, the country remained poor and underdeveloped.

Seven years after emancipation, sectarian parliamentarians deployed corruption and political tribalism to defeat the founding president of the republic and his reformist prime minister in the presidential election of 1967. As President Aden Osman relinquished power, he warned the new authority and the public that “without democracy nothing good can happen”.

The new regime failed to heed the wisdom of the elder statesman, with tragic consequences. They immediately dropped the anti-corruption agenda of the former government and then enrolled traditional leaders in the parliamentary election of 1969.

This move reintroduced the colonial strategy of inscribing ethnic differences as political differences among Somalis. That scheme led to the creation of 63 political parties, the vast majority of whom represented single candidates for parliament.

Once the dust settled, all successful single-party candidates joined the ruling party in the hope of either gaining ministerial posts or money. The political rot at the very top alienated most citizens, which led them to welcome the military coup of 1969.

Sensing the public’s hunger for a clean government, the military embarked on what appeared to be a progressive agenda to legitimise itself. The honeymoon lasted for several years before the dictator and his collaborators fully tribalised all government institutions, including the military.

Sectarian opposition groups took a leaf from the regime’s toolkit and organised armed opposition groups along tribal lines. The regime collapsed in 1991, and the country fell into the hands of competing tribalist factions and warlords.

Somalia became the first failed state in the world, resulting in the death of nearly a million citizens and millions of others were displaced.

But the most tragic and enduring outcome of the catastrophe has been the loss of the people’s civic commonalities and national character. Without such identity, Somalis have been unable to rebuild their lives and country.

Fifteen years after the collapse, a group of Muslim clerks, known as the Union of Islamic Courts (UICs), mobilised Mogadishu’s residents and successfully defeated the warlords in 2006.

Rashly, the American government and its African allies undermined this grassroots uprising, labelled the UICs as terrorists, and endorsed a tribalist Somali government formed in Nairobi, Kenya.

Further, America supported the Ethiopian invasion of Somalia in 2006 under the pretext of fighting terrorists. This marked the birth of al-Shabaab.

Reinforcing the cage of corruption and political tribalism

Twenty years after the Somali Federal Government and provinces were set up, the cancer of corruption and political tribalism continues to erode the last vestiges of civic life.

Ever since 2000, Somalis have been segregated into tribal political camps. Similarly, the regions have effectively become “Bantustans” for particular genealogical groups and each is under a tyrant.

As a result, MPs and political leaders at all levels of government “represent” particular tribal groups without any common civic vision for the country. Further, ministries and other public offices have become corruption havens for tribal political elites.

Such structures have transformed government operations into sectarian corruption fiefdoms. Under the tutelage of the deeply opportunistic leadership at all levels of government, those seeking services from the state are forced to become clients.

What is more frightening is the fact that young people, who constitute nearly 75% of the population, have never experienced a democratic government where citizens have equal rights and where political ideas do not have a tribal hue. Consequently, the vast majority of the population have little understanding of the notion of civic belonging.

The public school system that would have nurtured common citizenship has been in tatters since the state collapsed in 1991. Today, most of the schools and universities in the country are privately owned and do not offer any kind of civic education, nor do they teach the country’s history.

Thus, there do not exist any type of formal or informal institutions where civic ideas and identities are nurtured.

The tragic consequence of such an environment is that the most salient identity of an individual is one’s tribe. As such, the young have internalised tribal political identity and appear incapable of imagining a more progressive way of being a Somali.

The “naturalisation” of such “culture” further strengthens the power of the crooked and tribalistic elite. These are the forces that have transformed the country from being a model of democratic practice to a paradigmatic disaster. Yet, there is a growing sentiment among some of the youth for a civic and inclusive future.

The warning for Africa

If Africa’s culturally most homogenous country fell prey to sectarian and self-indulgent elites, no other country can possibly be immune from the scourge of corruption and tribal politics. As a result, four types of countries exist on the continent.

First, there are the countries that have collapsed, best exemplified by Somalia, Libya and Sudan.

Second, others that are on the edge of the precipice include South Sudan and the Central African Republic.

A third group of countries that are in worrisome conditions includes Ethiopia, Chad, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Gabon and Mozambique.

Finally, troubling signs are on the horizon even for some of the so-called African democracies like Kenya and South Africa.

The fundamental cause of Africa’s recurring crises and calamities are corrupt elites who undermine the collective civic commonalities of their nationals. They do so by transforming cultural identities into divisive political wedges between communities.

The elites’ myopic agenda is to prolong their tenure in power in order to loot whatever resources their countries possess.

The suffering of our people in many parts of the continent is biblical. As an African academic, a senator in the Somali parliament and a member of the Pan-African Parliament, I have seen up close the markers of deep decay in African politics and leadership, and the subsequent suffering of our people.

The cause of the Somali political calamity appears to be everywhere, with some exceptions. Elite malfeasance is a flashing red light that the rest of Africa can ill afford to ignore any longer.

Abdi Ismail Samatar is a senator in the Federal Parliament of Somalia, an extraordinary professor in the Department of Political Science at the University of Pretoria and professor of Geography at the University of Minnesota. He is the author of the recent book, Framing Somalia: Beyond Africa's Merchants of Misery (Red Sea Press, 2022).