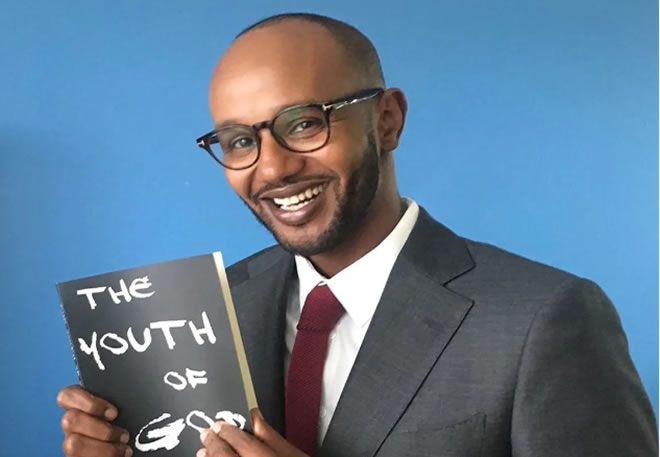

by Abukar Sanei

Wednesday January 25, 2023

The setting of The

Youth of God is in Toronto, Canada, and the main message of the novel is to

narrate the living condition that the Somali immigrants in Canada are going

through. However, before getting further into the themes and details of the

novel, it is important to provide some background information about why Somalis

immigrated to Canada. The answer of this question goes back to the “push and

pull” factors that theorize why people leave their country. In 1991, Somali

state collapsed after clan militias overthrew the government of Mohamed Siad

Barre, a socialist leader who has been in power since October 1969. After the

overthrow of the government, civil war between clans ensued in the country as

many people lost their lives and others fled the country to seek refuge in

neighboring countries, such as Kenya, Ethiopia and Djibouti. Furthermore, in

1992, a severe drought hit the country, and caused malnutrition in vulnerable

groups, such as women, children and elders. The UN Peacekeeping Office reports

that as of the early November 1992, 3000 people were dying on a daily basis due

to the famine, and the total estimated number of those who died was 300,000

people (UN Peacekeeping Office, n.d). Insecurity due to the civil war and

famine that was the result of the drought led many Somalis to leave the country

as they became refugees in many parts of the western Europe and the two main

north American countries, the United States and Canada. In Canada, Berns-McGown

(2007) reports that Somalis began arriving in Toronto, and other western cities

in significant numbers in the early 1990s [as] the vast majority arrived as

refugees (p. 234). With that brief background in mind, however, The Youth of

God brings three themes. These themes are loss of identity, belonging and

nostalgia.

The main

fictional character of The Youth of God is a young boy called Nuur who

embodies a loss of identity even though he is a first generation of a Somali

descent in Toronto, Canada. There are two more characters that are closely associated

with Nuur as they try to influence him to regain some sort of identity. These

two characters are Mr. Elmi, who is Nuur’s biology teacher at his high school and

imam Yusuf who is based in a local mosque in Toronto. Religion could be where

Nuur is looking for his identity as he is depicted very religious in the novel.

In his school experience, Nuur is very bright, but he is routinely bullied by

his classmates, specially James Calhoun and two other students. He is bullied

mainly for four reasons: first, he is Muslim; second, unlike any other typical

high school student, Nuur has a big beard; third, he wears qamiis, a long

garment that covers the entire body worn by men in the Middle East, and fourth,

he makes his ablution, or wudu ( a cleaning of the palm, face, hands and feet that

is done before the prayer) in the bathroom sink, which is only meant for

washing hands after the use of the bathroom.

Qamiis, as the

Somalis call it, is a cultural clothing for the Middle Eastern and North African

men, and it does not have any religious meaning, but the Somali people see that

dress code as a “religious” dress, because religious scholars wear it. However,

as Nuur wears it to school, he is called “Osama” or “Bin Laden” or “Al-Qaeda

Boy” (p. 4) by his bullies. This is one example of loss of identity that the

young Somali men in the diaspora are facing where some of them are not

embracing the new culture that adopts them as they are not also well versed the

Somali culture background that they came from. The religiosity of Nuur is also

very visible in his dealing with his own brother, Ayuub as he takes his

concerns to imam Yusuf. “What do you do when someone you love is on the wrong

path? The wrong path, the imam repeated. Yes, the wrong path, Nuur said, the

path to hellfire” (p. 22). This line refers to when Nuur saw his brother

sleeping with a white Canadian girl that he is not married to. Throughout the

novel, it is clear that Mr. Elmi tries to establish a very good connection with

Nuur as he sees that there is a potential in him. As a teacher, Mr. Elmi

understands that the young man needs someone who can provide mentorship and a

sense of identity. “I want to give you something before class, Mr. Elmi said. It

is just a book. Thank you, Nuur said and read the title mouthing the words

slowly as if considering their meaning, “I didn’t realize Descartes made an

error,” (p. 76). In his interaction with Nuur, Mr. Elmi puts emphasis on the

well-known five words that are attributed to Descartes: I think, therefore I

am. As wearing qamiis might be an issue for Mr. Elmi, by giving Descartes

philosophy, he is indirectly telling this young man, “be yourself and don’t

imitate anyone blindly.”

On the other

hand, imam Yusuf has an interrupted access to Nuur as he tries to sway him from

“this worldly life” For imam Yusuf, “serving God’s path is the ultimate goal in

this life; school is not important. “The loss of faith” he tells Nuur, “is what

put Muslims where they are today” (p. 77). Imam Yusuf continues his indirect

recruitment of the young boy to radicalism as he even questions the faith of

Mr. Elmi. Imam Yusuf tries his best to gain the full ownership of Nuur. The

brightness of Nuur in school, and his ambitious to enroll in the University of

Toronto is not an issue for imam Yusuf. He tells Nuur that so many of Muslim

men of your age have no such desire. They are more concerned with going to

university and getting jobs and buying nice things. But as you and I know, for

a true Muslim man, his house is not in this dunya (this worldly life). A true

Muslim seeks a home in paradise (p. 114). As Mr. Elmi wants Nuur to go to

university, imam Yusuf attempts to tarnish the credibility of Mr. Elmi by asking

Nuur, “does he come to your Friday Khutba? How much does he know about Islam?”

(p. 115). As any extremist or recruiter would do, imam Yusuf shows Nuur his

rejection of democracy all forms of secular governance. “Their democracy, this

thing they want to infect us with, is not a simple case of choosing a president

or prime minister. What they want from us, no, what they demand from us is

nothing short of the removal of the word of Allah from all public life (p.

118). As Nuur was expelled from school because of a fight and his father kicked

him out from home, imam Yusuf puts Nuur in “The House,” which is a

recruiting home for those who will be deployed to Somalia to join al-Shabaab.

As the recruitment completes, imam Yusuf arranges all the process of Nuur’s traveling

from Canada to Somalia through Kenya.

Belonging is the

second theme that is narrated in the novel. Even though Nuur was born in

Canada, his attitude and behavior do not portray that he belongs there. Of

course, there is nothing wrong with being a practicing Muslim and a Canadian at

the same time, but Nuur isolates himself in an extreme way. In the entire novel,

there is no single paragraph about Nuur having friends either Canadians or even

Somali-Canadians of his age. The only two people that Nuur is associated with

are Mr. Elmi and imam Yusuf. Moreover, Khadija, Mr. Elmi’s wife, reveals that

Canada is not where she belongs. Ghedi narrates that for months after their

wedding, Mr. Elmi had felt shut out of his wife’s interior world, as though she

were punishing him for taking her so far away from the only place and people

she had ever known and loved (p. 96). The issue of belonging could be a

phenomenon that Somali immigrants face in the diaspora, and one of those young

men who was recruited from the United Kingdom to join in the ranks of

al-Shabaab expresses his feeling about the isolation that he has witnessed. “I

was directionless, unhappy, and of no use to me or anyone else…I was unemployed

and treated like a second-class citizen in [my] own so-called country. The

kafir (infidels) talk that talk about multiculturalism and all the rubbish, but

they don’t walk the walk, do they? But I warn you, my young Muslim brothers,

don’t believe their lies. Their land will never be our land, yah” (p. 175).

Nostalgia is

another theme that Ghedi narrates in the novel via Mr. Elmi. In the depiction

that Ghedi portrays, Mr. Elmi can be considered as an integrated person in his

life in Canada. However, after a short visit to Somalia, he comes back to

Canada and he was invited to a symposium by a Nigerian friend and former

classmate. The topic that he will address in the symposium is entitled,

“Unravelling Somalia: Interrogating the Politics of Diasporic Identity.” In a

story telling manner, in the novel, Mr. Elmi starts his address when the

airplane that was carrying him started descending into Mogadishu airport. “I

looked out the window of the plane” Mr. Elmi tells his audience, “and I saw the

shore of the Indian Ocean. The blue water and white sand dunes looked exactly

as I had left them. A warm welcome feeling of home enveloped me” (p. 58). In another recollection, Mr. Elmi reimagines

his past, “I closed my eyes, and saw myself as a boy, swimming at Liido,

Mogadishu’s famous beach. It was a Friday afternoon, and I was spending the day

at the beach with my family” (p. 59). This is an imagination that Mr. Elmi is

trying to recapture his childhood memory as he reconnects with the “good old

days” where everything was normal.

Mr. Elmi recounts

that the aroma of Somali tea, a concoction of loose-leaf tea, ginger, and

cinnamon steeped in boiling water and served with milk and sugar, was a delicious,

Proustian experience transporting me back to a lost time. A time that will

never be regained (p. 60). If this was the old life that Mr. Elmi lived in his

early life in Mogadishu, what are the changes that he is witnessing during his

revisit of his country of origin? Through the personification of Mr. Elmi,

Ghedi narrates that nothing is normal in a city that was ruined by a civil war with

clan warlords in the early 1990s in one hand, and by the extremist group

al-Shabaab that has been in a constant fight with the government of Somalia

since 2007 on the other. The theme of nostalgia is very visible in the

narrative when Mr. Elmi visits his “childhood home near the famous Bakaare

Market” (p. 61). On his way, he passes by the “dilapidated National Theatre,

and asks the driver to stop so that he could take a few pictures as he felt

guilty to just drive by the place where he saw his first play at the age of

thirteen (p. 61).

The Youth of God clearly

narrates the themes of identity loss, belonging and nostalgia as they are part

of the experiences that Somali immigrants in Canada in general and in Toronto

specifically are going through. As Nuur, the main protagonist of the novel

reveals, loss of identity makes him so vulnerable as it leads him to be easily recruited

for al-Shabaab agenda. Mr. Elmi and the parents failed to detect the

vulnerability of Nuur to become a victim for radicalism. However, as The

Youth of God fictionally depicts the scenario of radicalism and

recruitment, and there are some possibilities that it might happen in real

cases, there is no way to assume that all religious centers/mosque are places

for recruitment. The young Somali-Canadians yearn to find where they can

belong, and this is where the authorities, local leaders and parents should pay

attention to by providing opportunities that can protect the youth to become a

prey for radicalism and jihadism objectives. Finally, as Mr. Elmi is portrayed

as someone with nostalgia in the novel, it is a condition that the old

generation in the Somali diaspora lives with as those who can get the

opportunity to do so may wish to visit the country and see the memorable places

that they had spent time in their childhood.

Abukar Sanei is

a Ph. D. Candidate at the Scripps College of Communication from Ohio

University, Athens, Ohio. His research focus is media and migration and the

diaspora communities. He can be reached at [email protected]