Mohamed I. Trunji

Friday October 19, 2018

By late 1960s, signs of growing tensions came to the surface in Somalia becoming a lot more evident between 1967 and 1969. Much of the hope with which Somalis greeted independence in July 1960 had evaporated: too little had changed for the better. Successive Somali governments focused their attention on the conflict with neighbouring countries, relegating social and economic problems to the bottom of their priorities list. Somalia’s major foreign policy was to unite under its flag the million Somali speaking people living in Ethiopia, Kenya and French Somaliland. This policy provoked years of costly guerrilla activities and savage retaliation.

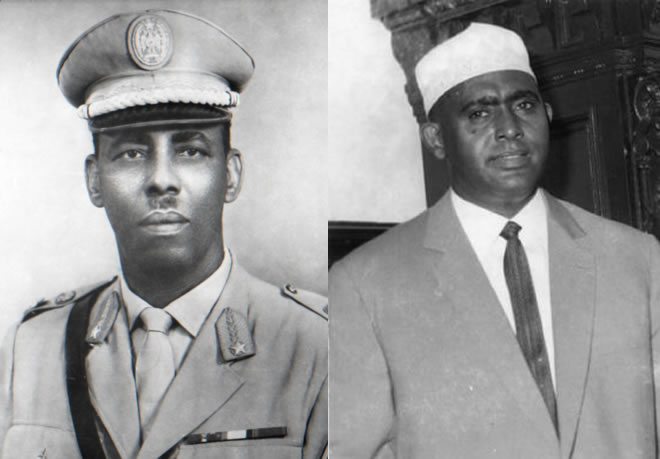

The presidential election of June 1967 brought about the appointment as Prime Minister, Mohamed Haji Ibrahim Egal, a thirty-eight years old hailing from the former Protectorate of Somaliland, a politician with the reputation of pragmatism who believed that the interest of Somalia was better served by his own brand of detent with the neighbouring countries.

The 1969 political elections, the third and last elections in the country, were held in March of that year for 123 National Assembly seats. Rivalries between clans caused the fragmentation of political parties into smaller and smaller units. This explains why over 60 political parties contended in the elections. Whatever Somali voters may have wanted, it was axiomatic that the Lega party did not lose elections. So, gross irregularities in the 1969 election should come as no surprise. Rumours of a military coup were widely circulating, but the government seemed not showing sign of alarm. The opposition remained largely divided without a common programme, fragmented, as had always been the case, along tribal lines. The question that arose was whether a polls victory obtained by unethical means would enable the ruling elite to govern until the end of the legislature, set to end in 1974, or throw the country back into tribal enmities and chaos. The election fraud was only one of the fuses that could detonate an explosion at any moment. Discontent was exacerbated when the Supreme Court, rejected on procedural grounds, all petitions and complaints filed by political parties against decisions taken by local authorities.

It was in the field of foreign policy that Egal chiefly broke new ground. He did in fact appear to have good foreign policy advisors, but for domestic affairs he heavily relied on bad advisors who pushed him to make fatal mistakes which eventually brought his premature downfall in 1969. Mohamed Haji Ibrahim Egal could have gone down in history either as a leader who guided Somalia towards stability, or as the man who scotched its chances of better future. Sadly he displayed some of his southern brothers’ ugly traits. But, while the southern political classes were experts in electoral fraud and had been in that ‘business’ since 1954, Egal seemed to be a complete novice in domestic affairs, and as such, he handled the elections clumsily by just blindly following in the footsteps of his southern big brothers..

The Assassination of President Shermarke

A frenetic search for a successor

All over suddenly, on October 15, 1969, Radio Mogadiscio gave the shocking news that the President of the Republic had been shot dead at about 12:45 in Las Anod by a rogue policeman. The readers might perhaps be interested to learn that, a year earlier, the President had survived an assassination attempt narrowly avoiding a grenade attack while being driven from the airport to Villa Somalia. It soon emerged that the earlier assailant was a close relative of the rogue soldier who gunned down the President in October 1969.

The President was visiting the northern provinces of the country that had been hit by famine and drought which has devastated the entire Migiurtinia (now Puntland) province, and the districts of Burao, Las Anod, Erigavo, Garadag and Las Koreh.

A sense of void of State authority was felt in the first hours following the death of the President, particularly when rumours started circulating that it had proven impossible to even send news of the tragic event to the Prime Minister, who was on state visit in the USA. After the official visit, the Prime Minister appears to have taken some days off at Las Vegas, as a guest of the American Hollywood film star, William Holden. “The Somali Embassy in Washington took the trouble to seek the FBI’s assistance in order to locate the whereabouts of our Prime Minister” (Mohamed Aden Sheikh, 2010) .When the ‘missing’ Premier was eventually located and informed of what had happened, he hastily returned to Mogadiscio. Soon after his arrival, he and his party’s leadership started the selection process for a presidential candidate. The choice finally fell on Haji Mussa Bogor, a consummate politician and close associate of the slain President.

A brief profile of the prospective candidate for the presidency is in order. Haji Mussa was the son of Boqor Osman, the last King of Northeastern Migiurtinia Kingdom. He was one of the most prominent members of the Lega party and one of the five members of the Territorial Council of the party during the initial period of the Italian trusteeship administration (1951-1955). Between 1956 and 1959 he served as Minister of the Interior in the two governments under the premiership of Abdullahi Issa, but serious differences with the Prime Minister, led to his dramatic resignation in 1959. From 1959 he represented uninterruptedly the Alula constituency, the coastal town in the northern east Migiurtinia (now Puntland) province.

The public, still in shock after the brutal murder of their beloved President, also had to come to terms with an ugly hiccup in the burial arrangements when local tribesmen, claiming traditional title to the burial site, demanded payment in exchange for permission to perform the burial rituals. Left with no choice, the government succumbed to the tribesmen’s challenge, “The government, wanting to avoid confrontation, decided to yield to their pressure and paid them astronomical amount of money,30,000 Somali Shilling, for the public land” (Abdirazak Haji Hussein 2017, p, 292)

The presidential election was set to take place in compliance with article 74 of the Constitution in the following day on October 21, 1969. But, on that date, no election took place, and the National Assembly did not meet as planned, because, “When, at a late-night meeting at the party HQs on October 20, the party caucus reached agreement to present this nominee as their official candidate, thus virtually ensuring his election as President and Mohamed Haji Ibrahim Egal’s re-appointment as Premier, those army officers who were closely watching development decided to act” (I.M. Lewis, 2002) Twenty-four hours after the state funeral of the slain President, a self-styled military victory revolutionary council seized power without bloodshed.

The critical three months preceding the military take over, was characterized by length and repeated absence of both the President and the Prime Minister from Mogadiscio. In fact, official records show that the President and the Minister of Interior went on friendly visit to Egypt on 10th July. At the end of the official visit in Egypt, both the President and the Minister proceeded to Italy on private visit. The President came back to Mogadiscio on 1 August while the Minister of Interior returned home on 19 August, i, e, 38 days after he left Mogadiscio in July. The Prime Minister left Mogadiscio on September 5 for Addis Abeba to attend the African Union Summit. On September 19, the President, together with the Speaker of the National Assembly, left for Rabat, Morocco, to attend an Islamic Conference and came back on September 28. Three days later, on October 1, the Prime Minister left, via Rome, for the United States of America, accompanied by a number of cabinet Ministers. A week later, on October 7, Abdirashid, together with the President of the Parliament, left Mogadiscio for an extensive tour to the draught-stricken areas of the country. The military had obviously exploited these circumstances to stage the coup, which most probably would not have taken place had the three top State authorities not been absent from the capital. “There could have been no better situation for the army and its Soviet advisors to hatch a coup d’état,” (Mohamed Diriye Abdullahi, 2001).

Barely six months since the elections were held the entire political scene was suddenly thrown into turmoil by the military, and Egal and his fellow party members had little time to enjoy their stolen victory. This military takeover was quickly dubbed a ‘revolution’. Explaining the difference between revolutionary movements and military takeover, Bernard Lewis wrote: “The word ‘revolution’ has been much misused in the modern Middle East, being applied to, or claimed for, many events which would more appropriately be designated by the French coup d’état, or the Italian colpo di Stato. […] Interestingly, the English language does not provide an equivalent term.” (Bernard Lewis, 2003)

The new military regime suspended the Constitution and the other constitutional organs (judiciary, parliament, political parties, freedom of speech and association). The country’s name was immediately changed into “Somali Democratic Republic”, a formulation that in Africa usually, albeit not always, signifies an intention to move to the left.

At a time when almost all African States had experienced some sort of a military coup or plot, Somali civilian leaders seemed not to have given much thought to that danger, choosing instead to believe that a military take over was not a method of changing the government of their country. The military takeover was welcomed with open arms by the public at large, not because the army looked best, but because the population was sick of the corrupt and inept civilian administrations led by the Lega dei Giovani Somali party since 1956. Many had lived off the patronage of the civilian-led government when it was in power, but no group or individuals lifted a finger to defend it; or even stage a protest; everyone melted away into the mass of people who, incognizant of the danger, welcomed the military

The military ruled the country for over 20 years, in the course of which, except perhaps in the first few years, their celebrated merits were few and very modest in the face of dramatic failures in foreign and domestic policy coupled with military adventure against Ethiopia which proved to be a fatal miscalculation. Like the civilian regime they ousted in 1969, the military too soon ran out of ideology and sense of direction. At the end, the night between 26 and 27 January, 1991, Jaalle Siad, abandoned and betrayed by his once loyal Red Helmet Presidential Guard, fled the capital, undercover of darkness, en voyage towards Kisimayo, bringing thus to a dramatic end a long and authoritarian military regime. The rest is history.

The trial of Askari Abdulkadir Abdi Mohamed

Meanwhile, the trial of Askari Abdulkadir Abdi Mohamed, regimental roll (matricola) 4745, later identified as Said Yusuf Ismail, which was pending before the Regional Court of Burao, territorially competent to hear the case, was transferred, for security reasons, to the National Security Court in Mogadiscio.

In the absence of reliable evidence, the tragic event had generated a jumble of contradictory accounts on the motives behind the killing of the President. Among these, the one linking the criminal act to alleged election rigging in Migiurtinia province, had gained the widest currency. According to this account, the killer appeared to have acted in reaction to the political violence which had caused the death of dozens of people, including some of his close relatives, in the electoral district of Iskushuban (Migiurtinia). However, the defendant denied acting on grounds of personal grudges towards the former President, admitting instead that he had acted in the “general interest of the country and the people”. (National Security Court ruling no. 37/70 Reg. Sent. no. 63/70 Reg. Gen., pp 20-22) The accused was found guilty of willful murder under article 434 of the Somali Penal Code (SPC) and sentenced to death on October 8, 1970, just less than one year since the tragic event at Las Anod. His five co-defendants were acquitted. However, for many, the conclusion that the murderer was alone in the preparation of the criminal plan to kill the President remains until today utterly simplistic to be convincing. The story seems to be missing a chapter, and many questions remain to date unanswered: what is the real story of the assassin’s time in the police force; why was he moved to Las Anod shortly before he shot the President; what role might have been played by possible instigators, widely rumoured at the time to be among the President’s rival politicians. These and other questions remain still unanswered

M. Trunji

E-mail: [email protected]