by Mohamed I. Trunji

Monday, May 15, 2017

In the wake of the defeat of the Italian fascist regime, the Somalis were unexpectedly ushered into a new era of political consciousness as they had never experienced in the past. They had actively witnessed and taken part in the devastating war between two European colonial powers. Italy, whilst initially having the upper hand in the armed conflict in the Horn of Africa, had lost out to Britain in the end. Like many other Africans involved in a war which was not theirs, the Somalis derived from exposure to the conflict’s dynamics a dramatic and lasting psychological effects: a sort of eye-opener which left them with the conviction that their European rulers were not invincible, but weak and vulnerable, like any other human being.

Through the powerful British propaganda tools, the Somalis were aware of the establishment of the United Nations in 1945 and of its programme calling for the independence of peoples under colonial rule. No political parties existed in Somalia other than the Fascist Party to which only Italians were associated. The British Military Administration (BMA) favoured free expression of political opinion in the territory, subject only to certain safeguards to ensure the preservation of law and order. The activities of the parties were regulated under a BMA proclamation, the primary purpose of which was to establish adequate control over these associations during the period of military administration.

The proclamation required any group wishing to establish itself as an organization to obtain the consent of the district civil affairs officer. His consent was also required in order to organize processions and gatherings, to issue orders to the population, publish any notices or collect any subscriptions other than those provided for in the by-laws. Propaganda for, or against any other organization or part of the population which might create public alarm or lead to a breach of the peace, was prohibited.

The associations or clubs that existed before 1947 were more social and charitable than political in character. The parties began to multiply and design political programmes in an effort to prove to the Four Powers Commission that each of them represented the will of the majority. The activities of the political movements were, however, confined to the urban areas, outside of which, as might be expected, there was little interest in political parties. Of the numerous political movements which came into existence shortly before the Four Powers’ mission to Somalia, only two, the Lega dei Giovani Somali and the Hizbia Dighil Mirifle, reached a high level of political development and had a clear political agenda on how to run the territory after independence.

The Somali Youth Club

As we have seen, the impact of a national idea on a people in the throes of violent social changes brought about by war produced the first beginnings of a Somali awakening and a Somali national movement aimed at the creation of an independent State. The first modern Somali social organization, the Somali Youth Club (SYC), was founded in Mogadiscio on May 15, 1943, but did not really become active until early 1946 when its membership began to increase. In the beginning, the SYC was primarily actively engaged in promoting social and welfare education and health programmes, targeting particularly the less privileged segments among its affiliates. However, it would be wrong to believe that the promotion of the social welfare of members of the Club could entirely be divorced from political matters. To help improve the new club, the British allowed the better educated police and civil servants to join, thus relaxing Britain’s traditional policy of separating the civil service from political parties “because the new movement was progressive, co-operated with the government, and was anti-Italian.” The SYC expanded rapidly and began to open offices not only in the British Protectorate of Somaliland, but also in Ethiopia’s Ogaden.

Two differing narratives explain the genesis of the Club. One explanation suggests that in early 1943, when the Italian community in Somalia was permitted to organize political associations, a host of Italian organizations of varying ideologies sprang up with a view to challenge British rule, and agitate, sometimes violently, for the return of the colony to Italy. Faced with growing Italian political pressure inimical to continued British tenure, British colonial officials encouraged the Somalis to organize politically. The movement spread like wildfire and became very powerful in areas as far apart as Ogaden and British Somaliland. Paradoxically, however, whilst the British administration in Somalia was favourably disposed towards the Lega, the Kenyan colonial authorities proscribed the Kipsingis Central Association and the Garissa branch of the Lega dei Giovani Somali throughout the country on July 13, 1948, deeming them “dangerous to the good of government of the Colony.” On June 4, 1948, the Garissa branch of the Lega was declared to be an unlawful society by the Governor; consequently, leaders of the party were exiled to the Turkana Province and not released until 1960.

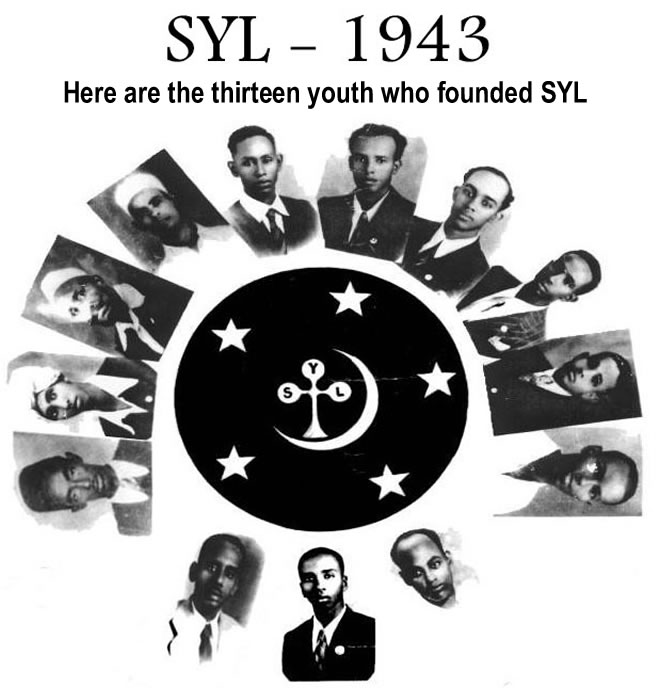

The second explanation of how the Lega came about, which received wide currency, indicates that the idea of establishing the party itself was the brainchild of a group of 13 little-known young urban Somalis. Somali historians place great importance on the date of 15 May 1943, the day when these 13 young Somalis came together, in a small one-room office in Via Cardinale Massaia in Mogadiscio and founded a club they called Somali Youth Club (SYC). The 13 youngsters have since been remembered as the precursors of the Somali independence movement. The group included elements representing the main Somali clans. Today there is no consensus among Somalis regarding which person in the group should be considered to have provided the main inspiration. Controversy over this very much debated issue seems to be fuelled by factionalism and devoid of any objectivity. Some maintain that much of the inspiration came from Yassin Haji Osman Sharmarke, the most erudite element in the group by Somali standards of the time. However, this notion is strongly contested by others who attribute credit to Abdulkadir Sakawa-din and Haji Mohamed Hussein, both prominent religious figures of ethnic Benadir. Yassin was an ethnic Majerten who served the Italian colonial administration as a clerk. He received a modest level of education at the ‘Scuola per figli di Capi’, a special school for children of Somali paramount chiefs during the fascist regime. Though lacking formal education, he was nevertheless a brilliant man, with sound political awareness. To implement his ideas, he needed two things: a vibrant membership of the Club and a programme which could be incorporated in a statute. He had no difficulty in co-opting 12 persons, selected at random and including his own brother, Dahir Haji Osman ‘Dhega-weyne’, to become the Club’s first members, representing the broader spectrum of Somali clan families. In Somalia, tribalism must be at the heart of everything, and Yassin was well aware of this reality, which he found hard to ignore. The majority of the co-opted members were semi-literate; they earned their livelihood doing menial jobs as shopkeepers, office cleaners, gate-keepers, etc, and none of them had ever been outside Somalia or come into contact with Western culture and civilization. As for the second requirement, it is widely believed, although there is no hard evidence, that Yassin received benevolent support from little known Italian communist elements in Mogadiscio in drawing up the Statute of the Club. Abdulkadir Sheikh Sakawa-din, grandson of the much venerated religious leader, Sheikh Aweys Al-Qadiria, was elected President of the SYC; Dahir Haji Osman Sharmarke was nominated as its Secretary and Mohamed Hersi Nour and Mohamed Osman were members. The Club’s constitution did not refer clearly to the political future of the country. The Club’s political aims were limited to two objectives : firstly, to unite all Somalis, particularly the youth, by eradicating harmful prejudices likely to lead to and frequently cause communal and tribal frictions; and secondly, to educate the youth in modern ideas and civilization through cultural circles and through the establishment and expansion of a formal education system based on schools..

The Club becomes a political party: its rise, decline and fall

In April 1947, the Club became a fully-fledged political party; its name was changed from Somali Youth Club (SYC) to Somali Youth League (SYL). In spite of the adoption of a new name, people continued to refer to the League as ‘Kulub’, a corrupted and shortened reference to the Youth Club. The official newspaper of the time, The Somalia Courier, reported the momentous event in its article heralding the changes. It wrote: “On the 1st April 1947 a new era started for the Somali Youth League. In fact, it may be said that childhood was over and manhood was reached. On that date the name was changed from Somali Youth Club to Somali Youth League, the latter being more suitable for the widening interests and development. The foundation date of this League is still considered to be the 15th May 1943 but the 1st April is the date that marks the renaming of the Club, the passing of a new constitution and framing of a wider programme. This will be an important date in the history of Somalia.” The new party adopted two additional objectives and appended them to its amended constitution. The first was the elimination of any situation prejudicial to Somali interests and the second was the adoption of Somali as the national language, using an existing script known as ‘Osmania’, invented by Yassin Osman Kenadid, a Somali nationalist, in 1920, as the national script.

Party membership was open to any Somali over the age of 15. It would appear, however, that membership was initially open to men only; women were allowed to join as members and pay subscriptions following the Party Congress of 1950. Upon joining, new members were required to take a solemn oath to abide by the objectives of the party: “I swear by Almighty God that I will not take action against any Somali. In times of trouble, I promise to help the Somali. I will become the brother of all other members. I will not reveal the name of my tribe. In matters of marriage, I will not discriminate between the Somali tribes and the Midgan, Yibir, Yahar and Tumal.” Nothing is said with regard to persons of Bantu descent. Whilst no one would doubt the good intentions of the person or persons who composed these slogans, one would be incorrect in concluding from this that tribalism and personal ambition no longer flourished within the party. Combinations of good intentions and tribally divided societies have never had a happy outcome.

The Lega differed from the other political parties in two important aspects: firstly, it was led by the best educated elements of the time, and secondly, its financial resources came from monthly contributions from members throughout the territory. The party had undergone structural reforms and expanded its scope and political programme; however by 1947, of the 13 founding members of the Club, only Haji Mohamed Hussein was actively engaged in the party’s business. Yassin Haji did not live long enough to see the evolution of the Club into a political party – the creation of which he had greatly contributed to. The remaining 12 ‘founding fathers’ did not play any significant role in the party’s business, being overshadowed, as later events were to prove, by relatively better educated and more active elements who took over the control of the party. A good number of the 13 ’pioneers’ had repudiated the Club before it became a fully-fledged political party in 1947. For instance, Dere Haji Dere, one of the founding members of the Club, appeared before the Four Power Commission of Investigation in January 1948 as member of the Hamar Youth Club49. Abdulkadir Sakawaddin, the President of the Club, had publicly denounced and repudiated the Club for reasons which remain to this date shrouded in mystery and subject to different interpretations. Some suggest that Sakawa-din was expelled from the party on grounds of alleged contacts with the Italians, the nature of which, however, has never been fully disclosed. Mohamed Awale, a Central Committee member, is reported to have informed the British Police that Sakawaddin had allegedly been coerced “at the point of a pistol” by an Italian medical doctor to sign a pro-Italian declaration, but failed to disclose the contents of the declaration. However, according to British intelligence sources, Abdulkadir had repudiated his former party on the grounds of disagreements over policy: his Islamist teachings clashed with the secular policies of his colleagues. During a religious sermon he delivered at Shingani Mosque, he is reputed to have told his listeners that at its inception, the Lega had laudable aims, but that it had since resorted to violence, and for this reason he had left the party. By the limited evidence available from credible sources, the allegations of betrayal leveled at Sakawaddin call for reserve. The man was very influential in the party and was not only highly respected, but also considered a martyr by the other members of the Club. Apart from Haji Mohamed Hussein, none of the 13 founders played any significant role in pre-independence Somali political life. With regards to the Administration Service, only Dahir Haji Osman and Ali Hassan ‘Verdura’ held any posts of responsibility in the civil service after independence. Dahir became a top civil servant at the Ministry of Interior and Ali became a top diplomat in the Foreign Service.

The structure of the party included a unit named ‘Horseed’ (roughly meaning ‘action squad’). The organization, founded on February 7, 1947, was mainly composed of young activists, chiefly responsible for maintaining discipline at party meetings. Virtually a private militia, Horseed was tasked with using any form of intimidation, including physical attacks, against their political adversaries.

By 1956 the party had begun to show signs of strain already pointing to its subsequent disarray. The antagonism and competition between the Darod and Hawiye tribes risked on more than one occasion bringing government activities to the brink of collapse.

In the central committee of the ruling party, the difficult working relations and the often violent open confrontations between Darod and Hawiye elements cast a shadow over the future of the Territory as a united entity. In his detailed diaries, Aden Abdulla convincingly describes how, day by day, the ruling party was derailing from its founding principles and the risk of the country sliding into chaos was looming ahead.

Towards the end of the Trusteeship period, many historical party figures, for different and often personal reasons, started quitting the party. The first to leave was one of the founders, Haji Mohamed Hussein, followed by a score of other party leaders, the best-known being Sheikh Ali Giumale, Haji Farah Ali and Abdirazak Haji Hussein. All of them formed opposition parties as alternatives to their former party. The loss of high-profile figures was further evidence of a movement crumbling from within. The party also lost the wisdom and guidance of one of its most prestigious members, Aden Abdulla, who was elected President of the Republic. The position required him to be above the parties but he never shied away from playing the role of moderator among the feuding, power-hungry clan leaders present in the National Assembly and in the government.

By 1969, as a result of changes of leadership brought about by continuing internal divisions, what remained of the old guard of the party was merely symbolic. The party had lost much of its original nationalistic zeal, values and prestige and reduced itself to a Mafia-like organization in the hands of unscrupulous elements whose main drive was the lust for power and greed for wealth. The party’s popularity had hit rock bottom and, perhaps most importantly, the Somali public at large felt enervated by the behaviour of the political class and incumbents, who through electoral manipulation and corruption were squandering the nation’s economic resources for their own benefit. The party’s nationalistic values were hijacked by factionalism and sectarian division within the party itself, a circumstance that unfortunately paved the way for the military to seize power.

Mohamed I. Trunji

E-mail; [email protected]