Reviewed by Liban Ahmad

Book: The Suicidal State in Somalia: The Rise and Fall of the Siad Barre Regime, 1969–1991

Author: Mohamed Hagi Ingiriis

Hardback: 363 pages

Publication year: 2016

Publisher: University Press of America

Several days after a group of Somali military and police officers had overthrown the last civilian government of Somalia on 21 October 1969, Seynab Hagi Ali ( aka Bahsan ) sang a song from which following lines are drawn: guushiyo barwaaqada, gugeygaygu simay ( I am lucky to live to witness victory and prosperity ). Sentiments in the song are not less sanguine about a future than those of William Wordsworth on the French Revolution: "Bliss it was in that dawn to be alive". When the rebels ousted the military regime in January 1991, Radio Mogadishu played Waa baa baryay ( The beginning of a new dawn ), a popular Somali song sung by the late Mohamed Ahmed to jubilantly celebrate the 1969 coup d'etat. Is it easy for Somalis to escape the legacy of the Somali Revolution ( 1969-1991 ) and habits of mind associated with it to be able to write about it? Can a historian write about the revolution without adopting the revolution's demonological attitude to history?

An attempt to answer this question has come in the form of a new book by Mohamed Haji Ingiriis, PhD candidate in history at the Oxford University. Written 25 years after the overthrow of the military dictatorship, and forty years after the formation of the now-defunct the Somali Revolutionary Socialist Party, The Suicidal State in Somalia, which consists of eleven chapters, is based on interviews with Somali Army officers, politicians, businessmen as well as an archival research.

advertisements

The author implicates the KGB of the former Soviet Union in the untimely and sudden death of Commander of the Somali Army, General Da’ud Abdulle Hersi, to back the Deputy Commander, General Mohamed Siad Barre. Ingiriis blames Sharmarke-Egaal administration (1967-1969) for unwittingly speeding up Barre's plan to topple the civilian regime. Egaal's selection as a Prime Minister in 1967 was bankrolled by the CIA, argues Ingiriis, who relies on a paper published in 1974 but declassified in 2004. One conclusion that can be inferred from the paper in question is that the former USSR was betting on one man: the incumbent President. Ingiriis doesn't discuss why Moscow found a reliable ally in General Barre, who was then not known to have leftist sympathies. Clues to General Barre's preparations for the coup, Ingiriis writes, included his founding of the army troupe ( Xoogga ) after the death of General Da'ud, who was in favour a civilian oversight of the army and against the politicisation of the army.

For twenty-one years Somalis lived under what Wole Soyinka calls militaricians — "military in power"— whose leader's obsession with the presidency for life reversed early achievements of the Revolution and culminated in a reign of terror. The military regime executed by firing squad counter-revolutionaries in 1972 and 1978. Eleventh-hour efforts by business leaders, former civil servants and politicians through what came to be known as the Manifesto to persuade the dictator to relinquish power fell on deaf ears. The author posits a theory on the longevity of the regime: Barre rewarded loyalist clans by breaking up existing regions to create new regions on the periphery such as Gedo, Sool and Awdal. Those three regions were least developed compared to Banadir, Lower Shabelle, Middle Shabelle and Bay, where major development projects such as Lib-Soma and Bay Project were based. Of those four "centre" regions, Banadir belatedly produced armed opposition outfit — United Somali Congress — that, along with SNM and SPM, had succeeded to bring to an end a brutal military dictatorship. The core thesis in The Suicidal State can be summarised thus: Just as Barre plotted in the second half of 1960s to overthrow the civilian regime, he had plotted to deny Somalis the opportunity to produce leaders capable of effecting the post-Barre political change Somalis yearned for.

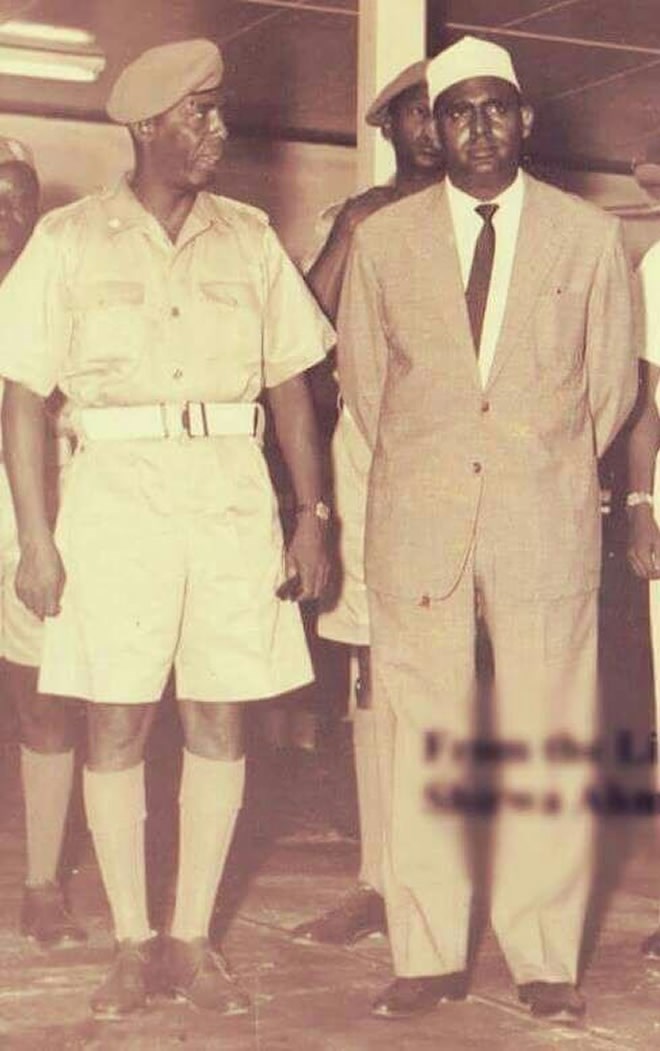

President Sharmarke (left) with Siad Barre

Allegations in the book include the former Somali Police Commander of the civilian regime General Mohamed Abshir Mussa, whom an informant describes as a mole for the CIA. The informant, Omar Salad Elmi, was the Chairman of the Party's Organisation and a member of the Central Committee before joining Somali Salvation Democratic Front based in Ethiopia. Mr Elmi is the source of the allegation that the late Omar Mo'allim "was an agent for the CIA". Another top-ranking member of the Supreme Revolutionary Council (SRC) whom Ingiriis describes a spy for Mossad, Israel's spy agency, is the Lieutenant General Mohamed Ali Samatar. The source of the spy allegations against Samatar is Brigadier General Mohamed Nur Galaal. Ingiiris has not labelled the former Somali Ambassador to the USA, Abdullahi Addou, a spy for confiding in "senior American diplomats that Somalia had 'virtually lost its independence' to the Soviet Union."

On the 1978 abortive coup in Somalia, Ingiriis writes: "... former senior military officers mentioned that Siad Barre visited Yusuf in a Somali-Ethiopian border town shortly after the war. Yusuf did nothing because he reasoned that, if he killed or captured [ Barre ] ... politicians... [ from a rival clan ] in the capital would seize the State in his absence" ( page 158). Ingiriis has misquoted Ahmed's account on President Barre's visit. Ahmed wrote that he had objected to the idea to assassinate Barre in Doolow for two reasons: (1) members of the SRC would take over and introduce a state of emergency (2) the assassination of the president could lead to uncontrollable intra-clan feuding.

When a soldier assassinated President Abidirashid Ali Sharmarke in Las Anod in 1969, "Lieutenant Colonel Abdullahi Yusuf Ahmed Ahmed, the deputy [ commander ] of the Northern sector of the the Somali Army 'impudently' asked a regional Police Commissioner 'which clan the assassin belonged' [to]". Ingiriis cited Ahmed's memoirs but, again, misquoted Ahmed's account of the assassination. Ahmed wrote: "I asked ‘ And who killed [ the President?’" . Ahmed did not say “yuu yahay?” ( who is he?/ which clan does he belong to?” The military government investigated the assassination of President Sharmarke but made confessions of suspects "confidential... [ and ] blocked the possibility of running a risk in case the case would return to them" ( p.53). The message got lost in the literal translation of a Somali sentence which, in correct translation, should read: ... in case they get implicated in the case.

Ingiriis quoted a source who alleged that Brigadier General Ismail Ali Abokor, a former member of the Supreme Revolutionary Council ( SRC) had been "Siyaad Barre's spy on Egaal's activities" ( page 67). Ingiriis communicated with Abokor by telephone to verify if Abokor had overheard a fellow SRC member "exhorting his clansmen to defend their regime...” Ingiriis denied Abokor the right of reply on the allegation that he had spied for Siyad Barre before the coup. Ingiriis has used an indirect quotation of Abokor's without verification.

He discusses nepotism during the military dictatorship but cites documents that have no historical significance for arguments he is advancing. "Acting similarly to a State within the State, [Abdi] Hoosh and other clan cronies were granted legal power to monopolise import and export business singlehandedly", Ingiriis writes. The source he cites to back up the cronyism allegation against Hoosh is Law Number 61 issued in 1975. The word tolayn was used in the Faafin Rasmi ah (The Official Bulletin). Tolayn (nationalisation) was used before the Somali government adopted qaramayn due to the clan connotation of tolayn.

The author uses a proverb as an epigraph for chapter ten. The proverb ( Been Fakatay run ma gaarto ("A propagated lie can never compete with a simple truth") succinctly conveys the task before Ingiriis to expose what he views as lies disseminated as scholarly works on Somalia. In Hubsiimo hal baa la siistaa ("To know something for sure, one would part with a she-camel"), Dr Giorgi Kapchits discusses the correct version of the proverb — Been fakatary runi ma gaarto (" the truth will not catch up with a runaway lie" ). In The Historian's Craft, Marc Bloch agreed with Somalis that truth is on the trail of a lie: "...the experience of life teaches, and that of history confirms, that any offence against the truth is like a net and that almost inevitably every lie drags in its train many others, summoned to lend it a semblance of mutual support."

Those shortcomings do not detract from the strengths of the book to revive interest in the Somali historiography. In a keynote speech at Harvard University in 2015, Professor Ali Jimale Ahmed of the City University of New York argued that legitimation crisis has affected Somali Studies. Epistemological inadequacies in the book — misquotations, misattributions and mistranslations — should leave no one in doubt that Somali Studies can be " de-ghettoised" if researchers engage with each other critically and empathically. The Suicidal State in Somalia will prompt reflections and discussions on the challenges facing a new generation of Somalists.

Liban Ahmad

[email protected]