Mohamed Omar Hashi

Monday, 26 September

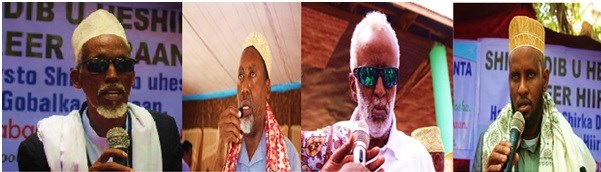

Ugaas Cismaan Ugaas Cilmi, Ugaas Cali Ugaas Xasan, Ugaas Xasan Ugaas Khaliif Ugaas Cali Ugaas Muxumed

Ugaas Cismaan Ugaas Cilmi, Ugaas Cali Ugaas Xasan, Ugaas Xasan Ugaas Khaliif Ugaas Cali Ugaas Muxumed

Based on a voluntary decision, two or more regions may merge to form a Federal Member State.

The Somali Provisional Federal Constitution

Article 49 (Clause 6)

Ugaas Cismaan Ugaas Cilmi, Ugaas Cali Ugaas Xasan, Ugaas Xasan Ugaas Khaliif and Ugaas Cali Ugaas Muxumed are prominent figures with noble-looking countenances, calculated to impress the beholder with other than resistance feelings towards characters who have been so much dreaded by the Federal Government. They have become national warriors, their names etched in all corners of the country. They represent the vast majority of the Hiiraan population, have stood up to the undemocratic and unconstitutional process spear-headed by certain individuals, who currently hold outdated public offices cloaked under the umbrella of a rather precarious legitimacy and the supposed support of the IGAD regional trade block. The traditional leaders directly opposed what seemed to be a deeply flawed process, on behalf of the people of Hiiraan, the supposed Hiiraan and Middle Shabelle state formation conference, held in the city of Jowhar, advocated for by the federal government, as defying the aspirations and challenging the political representations as well as the participation of their people towards the nation’s post-conflict reconciliation and reunification process. The reaction, in what appears to be a federal tug-of war, the central government officials have again and again pulled the rope very hard in the opposite direction. The traditional leaders understand the needs of their people as well as the root causes of division, oppression and injustice, and have devised calming and peaceful methods to counteract highly corrupt members of the federal government, who have been very adamant on enforcing their own vision of governance, non-reconciliatory, manipulative, point scoring, and aggressive mechanism, under the pretext of federalisation so as to further cement their grip on power and establish the right platform to win the upcoming general election/selection. The struggles the traditional leaders are leading are commonly held up as examples of social resistance at work.

From a theoretical perspective, this nation has adopted a federal system, in an attempt to end Somalia’s internal conflict and deep divisions, thus, as consequence satisfy the political needs of every clan. However, in practical sense, there is a significant adverse opinion, among the people, towards the design of the federal system. The bulk of the Somali public agree that the prevailing system has not been developed in a manner that would enhance the prospect of state rebuilding, in political terms, and that has failed to promote the concept of inclusivity to end the clan conflict and, more threateningly, the prospect of secession. Indeed, the opinion of the masses and evaluation of the federal system are crucial to the functionality and vitality of the Somali system. Yet, very little research is carried out towards the opinion of the Somali people in terms of whether a federal system of governance in this country would usher in a positive political trajectory towards stability and would accommodate the interest of the nation, considering all the barriers associated with the transition into a federal system, whilst at the same time being a fragile state. The case of Hiiraan and middle Shabelle sheds some light on the difficulties and complexities of the tasks ahead. A process that is fairly designed and transparent is required, so that federalism can take root amongst all the regions of Somalia. Certainly, some barriers appear to be rather inherent and somewhat inevitable in the course of moving away from the previous dictatorial and centralised system of governance, as well as the present clan power sharing arrangement towards a system of federalism. This country’s constitution permits the formation of federal member states, though it seems to apply stringent requirements that are tremendously challenging and complex for those assigned to build the various states that would make up the Somali federal system. Furthermore, the creation of federal member states may appear as a straight-forward process with relatively few obstacles, if any, it is very important to take into account the fact that of all the different regions of Somalia, there are very few clans, who are sole occupants of a particular region, let alone beyond two or more parts of the country. Hence, for any future member state to work, it would require incredible amount of reconciliation efforts in order to establish a state that transcends clan boundaries. Representatives of the Hiiraan population assert that prior to any decision to voluntarily move towards any state formation regarding Hiiraan and Middle Shabelle, the people of Hiiraan, first and foremost, must be given the opportunity to reconcile so that internal grievances within this region can be healed.

Furthermore, one critical issue that seems to make the division far more complex has to do with the mistrust between the people of Hiiraan and members of the federal government. One of the key reasons for this has to do with how leaders of the federal government appear to have clearly opted for, contrary to the voluntary norms and practices stipulated in the Somali federal constitution, rather top-down non-reconciliation coercive and bullying tactics, which are, in some instances, reminiscent of Siad Barre’s dictatorial regime. As stipulated in the Federal Government constitution, “Based on a voluntary decision, two or more regions may merge to form a Federal Member State” (Somali Constitution Article 49, Clause 6). The term ‘voluntary’ is used here, however the current government strategies are completely the opposite, suppression, alienation, division, manipulation, intimidation, etc. - further dividing an already polarised nation and embracing non-reconciliation tactics.Further, if one observes article 48 (clause 2) of the Somali federal constitution, it unequivocally stipulates that any region which decides not to join a state are to be administered by the central government for no more than two years. Because of the failure of the consultation, as well as virtually any form of agreement, some officials of the federal government have resorted to a number of non-constitutional means and, thus, by-passed representatives and aspirations of the Hiiraan population and rushed in to hold what is visibly regarded as a mock state formation conference in the city of Jowhar. The hopes and desires of the people, in this region, appear to be subordinated carelessly to the pursuit of federalism through an elite-driven political intervention, governed by widespread corruption, intimidations and marginalisation, which has alienated a large number of people in this significant region. Indeed, the rationale behind the prevailing process is in theory to establish new governance structures in Somalia, however in reality offers an opportunity to fatten the influence of political elites whose core motive is to reinforce their grip on power.

Out in the wilds of federalism policies, the citizens of Hiiraan region overwhelming rejected the prevailing federal state formation, yet those who lead the current federal government regard this as nothing more than a nuisance, to be massaged, contained or bullied; or, if these do not work, ignored. Rather than acknowledging the broad and uncontainable disapprovals of the people of this region, this government has chosen to stick with its failed strategic objective and because of this, it has accomplished the creation of a sort of pseudo-consent, the illusion of consultation, objectivity, as well as changed circumstance. Deeply embedded inside the Somali government’s federalism approach appear to be clusters of subjective driven meanings, values and assumptions. The problem with this is that it is very problematic in an ethical and moral sense, yet also seems to lack nationwide appeal, or relevance, for that matter. As numerous observers have suggested, the actual structure of the term federalisation vision does indeed encode a false sense of post-conflict reconciliation, as well as unification. The debates surrounding the Somali case expose the limitations of the approach and the lack of a clear language that encompasses the complexities of federalism as a subjective, which holds serious contradiction, inconsistencies as well as shifting processes marked by feelings of uncertainty, vacillation and the paramount need to contextualise. Rooted within the realms of federalism, the concepts of reconciliation and unification discourse are essential categories which do not, in all cases, accommodate the multidimensional experience or circumstance of participation. For example, the ongoing federalisation process, which in theoretical terms is conceived of as a process concerning two regions: Hiiraan and middle Shabelle, in the face of the overwhelming rejections of the targeted beneficiaries, the currently failed approach, appears to be firmly entrenched in the federal government’s practices and strategic setting, and because of this, hardly any attention was given to more complicated degrees of complicities like that found amongst recipients – the population of Hiiraan. These people are key stakeholders who have questioned the authenticity of the so-called inter-regional state formation conference in the city of Jowhar. The people of this region have not only rejected the conference entirely, but also indicated that they will not recognise any outcome from Jowhar. Moreover, the prevailing federal government vision, in Somalia, to create this inter-regional state, introduced serious questions as to whether this new political system, in this country, is capable of creating the stability that the people of this nation need and can it meet the governance as well as reconciliation desires in the medium and long term.

In order to overcome the unending cycle of internal conflicts and the urgent need to empower a legitimate system that embodies the will of the people, there must be a bottom-up approach. Keeping in mind that the very definition of legitimacy depends on whether the contractual relationship amongst the state and its population is working in an effective manner or not. The deeply worsening relations between the central authority and the traditional leaders and the people of Hiiraan as a whole, if not solved would undoubtedly precede a new long term political crisis, which would certainly represent a serious setback for this nation’s reconciliation and state-building process. The voices of this region have altered the political environment of Somalia and are proving to be an important force to be reckoned by questioning the significance of political participation. The political landscape in this region is set to be different from the one that existed up to this point, in which the demands and aspirations of the people of Hiiraan have, to a large extent, been disingenuously overlooked, ignored and ridiculed. Stakeholders’ competition in this country for either power or resources, social resistance, and the mixture of formal, as well as informal institutions in power-building policies suggest the significance of the concept of legitimacy. The concept of legitimacy is central, for there to be success in this process for the reason that, as for any specific set of decisions, the principle of an institution must be first accepted. In other words, legitimacy in this context can be described as a condition of the strength of federal member state institutional capacities and the paramount condition of the term stability. Paradoxically, this fundamental factor happens to be a managerial method to the state. The apparently ‘forced’ importation of exogenous political institutions in various regions of Somalia, particularly in the cases when there is clear failure to adapt it to local realities, introducing questions about the intention of such strategy. Clearly in the Hiiraan case, decisions are imposed and thus dramatically reduce legitimacy and nurture a deep social contestation and resistance. So as to tackle this stalemate and, therefore, create a sense of empowerment and a serious dialogue, as well as peace structures, the central government in Somalia must change its unsuccessful top-down hard-line state formation policy, in order to reach a long-lasting solution to the grievances of the people of Hiiraan.

The central government must work with both the Hiiraan traditional leaders and the grain of the people in the Hiiraan region, instead of imposing them. In this manner, the federal would help uncover much greater legitimacy, which in reality is a sine qua non for the establishment of an effective, capable and legitimate state in what is an extremely vulnerable setting. The concept of legitimacy becomes grounded if the system of government and authority begins to flow from it and is tied to local realities. The notion of grounded legitimacy highlights the normative feature of leadership and governance, which enables an association with and response to citizen’s values or beliefs on the ground. Somalia’s federal government has persistently attempted to create a Hiiraan-middle Shabelle state with hardly any grounded legitimacy. As a consequence, the government has completely failed to take into account the vulnerable environment and has thus resorted to predatory, or rather a coercive fashioned governance system, which is disconnecting and disempowering for many, consequently undermining the resilience and problem-solving capacity of the people of Hiiraan. So as to reinforce the legitimacy and effectiveness of the federal government, it is absolutely paramount to tackle non-state, informal, “traditional” kin and community sources of authority. In other words, it is important to find a way to somehow blend and hybridise legitimacy in order to create organic bridges concerning the past, present and the future. The significant point here is that organic grounded legitimacy would flow from the bottom-up, instead of top-down.

If political elites lack grounded legitimacy, then certainly, the rule will always be a rather precarious one. Internal, as well as external political actors, thus, need to engage with hybrid institutions with the intention of bridging Hiiraan and the federal government by opening ways to utilise community-level legitimacies for the purpose of state formation. Simply put, obstacles with the federalisation and the process of implementing it reflect the top-down concept of institutional building. This rather top-down concept is hitting up against the realities that virtually all Somali regional political processes, such as that of Hiiraan, are, in fact, more substantive. The idea of reaching consensus on its own is an untenable objective for anyone concerned with reconciliation efforts. In numerous instances, the perceived need for agreements towards how reconciliation can be achieved as well as what it could consist of, have hindered efforts toward that objective. The federal government needs to understand the prevailing problems with the failing federalisation policies and should take steps to address them. Failure to do so would lead to continued problems with any future federal state formation in this region, which could eventually usher in, or ignite deep tensions between rival regions within the member state. Heading into the last days of the government’s mandate in 2016, our traditional leaders’ voice and the Hiiraan people’s undisputed opposition cannot be overlooked simply as a political inconvenience.

______________________________________________________________________________________________________

Mohamed Omar Hashi was a Member of the Transitional Federal Parliament of Somalia from 2009 to 2012, and holds a Postgraduate Certificate in International Studies from the University of Staffordshire and an M.A. in International Security Studies from the University Of Leicester.

E-mail: [email protected]