Monday, December 12, 2016

By Mohamed Omar Hashi

Somalia filed a case with the International Court of Justice (ICJ) in 2014, requesting the court to review the maritime boundary in the Indian Ocean, between Somalia and Kenya. The country argued that diplomatic resolutions concerning the territory had failed and asked for a proper determination of the maritime boundary between the two countries. The maritime area spans beyond 100,000 sq. km, and it is thought to encompass huge oil and gas deposits. Somalia claims that Kenya desires the maritime borderline between the territorial seas to be a straight line from the parties’ land periphery, along the equivalent of latitude where the land borderline sits, through the territorial maritime - Somalia’s proclaimed exclusive economic zone, and the continental shelf. According to Somalia, the straight line infringes UNCLOS Article 7 and UNCLOS Article 15 and, therefore, Somalia claims the boundary between the two countries to be a median line as specified in UNCLOS Article 15 and the border of the exclusive economic zone and continental shelf to be determined in the three-stage procedure outlined in UNCLOS Articles 74 and 83.

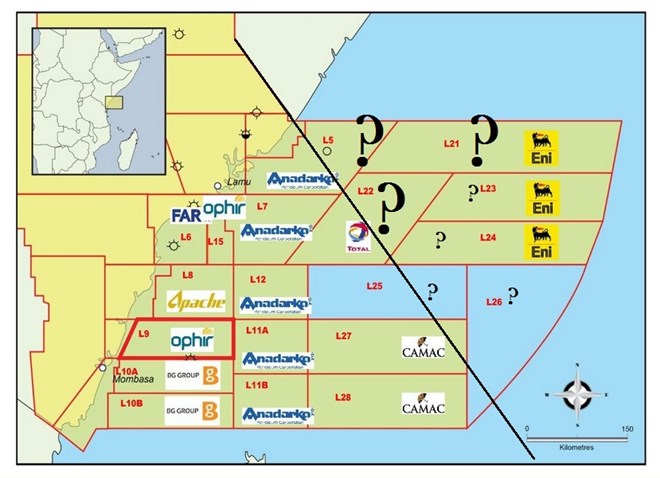

On 7th October 2015, Kenya submitted preliminary objections - challenging the admissibility of Somalia’s case and the ICJ’s authority to hear the application. According to Kenya, the two nations drew up a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) on 7th April 2009, which required them to handle their differences through the United Nations’ Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf (CLCS), and not through the ICJ. The MOU signed between the two countries was carefully assessed by the Transitional Federal Parliament of Somalia and the members of Parliament, who unanimously rejected its ratification on 1st August 2009. This rejection was communicated to the UN Secretary General, requesting to take note that the MOU was non-actionable for Somalia and from a legal perspective, non-actionable means NULL and VOID. The UN noted Somalia’s point on the MOU, when it published on its webpage the following note: “By a note verbale dated 2 March 2010, the Permanent Mission of the Somali Republic to the United Nations informed the Secretariat that the MOU had been rejected by the Parliament of the Transitional Federal Government of Somalia, and is to be hence treated as non-actionable”. The Somali legal team argued that the MOU only covered the outer limits of the continental shelf; however, this did not prevent the two nations from implementing other approaches to determine their borderlines. Even if Somalia was in breach of the MOU, which it is not, this will not preclude it from coming to the court. Therefore, Somalia argues that it determinedly defends its territorial sovereignty and maritime rights. In the meantime, considering the broader interests of peace and stability with its neighbouring country, Somalia has exercised great restraint and remains devoted to a peaceful resolution. However, diplomatic settlement has been exhausted and Somalia accuses Kenya of using the memorandum as a way of avoiding the case being taken to the United Nations' highest judicial organ. Somalia claims “deadlock has been reached” and that negotiations have proven futile, especially considering Kenya’s on-going annexation. For instance, Kenya spearheaded and deepened its expansion doctrine and annexation policy by opening eight new offshore blocks for sale to corporations, including L-5, L-21, L-22, L-23, L-24, and L-25 within the Somali maritime territory.

| Date | Martime Area | Kenya Awarded To |

| 2010 | Block L-5 | Anadarko Petroleum Corp (though subsequent reports appear to indicate that Anadarko gave up its interest in late 2012 or early 2013. |

| 2012 | Block L-21, L-23, L-24 | Italian company called Eni S.p.A. |

| 2012 | Block L-22 | French company called Total S.A. entered into a production sharing contract with the Kenyans to operate L-22 with a 100% interest and holds a 40% interest in the Anadarko- operated L-5. |

Kenya’s exploration of these blocks demonstrates its dishonesty toward genuine diplomatic engagement and a peaceful settlement of the dispute. This strategy, which violates Somalia’s territorial sovereignty, signifies that the future for interstate peace now hangs in the balance. Kenya’s expansionistic policy is predominantly governed by hegemonization of the Somali maritime at any cost. This is a risky political doctrine and deliberates transgression, which exemplifies why the Somali government decided to take the case to the United Nations' highest judicial court under the right circumstances. And as such, on 5th February 2016, Somalia submitted a response rejecting Kenya’s bid for an out-of-court settlement and proclaiming that it would seek justice only at the ICJ. Somalia argues that the Kenyan government is attempting to enforce its political power to justify its actions, that it is reluctant to change its hard-line strategy of demarcation, and that efforts to engage in dialogue are of no value to Somalia. The latter further argues that Kenya does not have any historic or other special circumstances that validate its claim. Somalia’s sovereignty and maritime rights have historic relevance, and are firmly governed by history and law. Kenya has invented numerous justifications to side-line this fact, and pursued its territorial pretension.

In the latest spiral, Somalia has secured a hearing on its case before the ICJ. The diplomatic agreement over unsettled maritime borders is essential for the avoidance of regional conflict. Somalia’s pursuit of peaceful settlement through the ICJ and its legal position is governed by a policy position that puts emphasis on national interest and a strong sense of entitlement connected to historical concerns over maritime sovereignty. Kenya’s strategy of intimidation has been undisputable, and it is unclear if this is part of a long-term vision and intended strategy; however, there is no doubt that Kenya has adopted an expansionist doctrine that is at odds with international law. At the core, intellectual penury is linguistic in nature. The propensity of Kenya is to divert discussion away from legal issue concerning the case to subjective based political spectrum. To do this, the mainstream media is capitalised. As with all metaphor, a pejorative term, of diseases when applied to society, Somalia is characterised as failed state and its internal conflict and migration are overpoweringly used as a political machine in order to divert the debate concerning the legal loophole surrounding Kenya’s expansionist strategy. Nor can these metaphors be condensed to mere popular descriptive embellishments, benignly ornamenting otherwise objective analyses. Closely interwoven with political, economic and sociological languages, metaphors of decay, collapse and illness are constitutive fundamentals empowering Kenya to take advantage of Somalia’s fragility – presenting itself to the international community as the helper of the needy Somali migrants, participants of Somalia’s counterterrorism, and securitisation efforts. These metaphors become the most potent legal and political allegory of Kenya’s strategy. Attorney General Githu Muigai who is leading the Kenyan delegation to the International Court of Justice (ICJ) used these metaphors to justify Kenya’s claims.

According to Mr Muigai, “There is a Swahili proverb that the person who helps you in need is truly your friend. Kenya played a decisive role in defeating Al-Shabaab forces and capturing Mogadishu. It has made significant contributions to both the civilian and military components of the United Nations mandated African Union Mission (AMISOM) in Somalia. Hundreds of Kenyan soldiers have lost their lives defending the Somali Government.” As such, these metaphors are widely echoed on Kenya’s mainstream media and public discourse, empowering idealistic, subjective and distorted narratives and by using such metaphors as a means to justify the ends. However, it is widely known that Kenya came to Somalia with its own strategic vision governed by creation of a buffer zone and is keen to work with Somali proxies to establish a more controlled along its frontiers. Kenya’s military has actually been accused of taking a cut of the illegal sugar and charcoal trade in Somalia that provides the bulk of funding for terror group al-Shabaab which it is meant to be fighting. Despite Kenya’s ill intentions, Somalia has maintained the channel of diplomacy open and welcomes the two countries’ cooperation and partnership in relation to interstate human security, counterterrorism, peace-building, trade, migration and developmental issues and so on. However, the country opposes any form of intervention and the widespread of politically constructed and fabricated metaphysic, and idealised depiction of Kenya as saviours of the Somali people out of tyranny - the maritime case is a legal matter that should be left to the ICJ to deliver its verdict.

To conclude, Kenya’s resistance to the peaceful settlement of case, and its objection of the case under the ICJ, suggests that it is willing to purse its expansionist strategy at any cost. Thus, if Kenya’s maritime coercion reaches a chronic stage and it persists to push forward the prevailing strategy, the Somali people, intellectuals, civil societies, women, youth, traditional clan elders, elites and statesmen must unite and stand together, rather than allowing the violation and demarcation of the country’s maritime sovereignty. This might include recalibrating our government’s policy on sovereignty pursuit. If there is an uptake in aggression, Somalia should consider this change in position, and implement it, if the ICJ’s final decision is not respected. One way of doing this could be the implementation of the Somali version of the Monroe Doctrine to protect its people, territory, livelihood, natural resource and common pool of resources for its current and future generations. With the Somali presidential election set before the end of this month, the new government vision and long-term strategy should be based on reviewing what actions by Kenya would force Somalia to revise its position on the peaceful resolution of the maritime dispute, and it may do so in a detailed and tailored manner, for the objectives of strengthening deterrence.

Mohamed Omar Hashi was a Member of the Transitional Federal Parliament of Somalia from 2009 to 2012, and holds an M.A. in International Security Studies from the University Of Leicester.

Contact: mohamedhashi74@gmail.com