by Hassan Mire

Friday, March 01, 2013

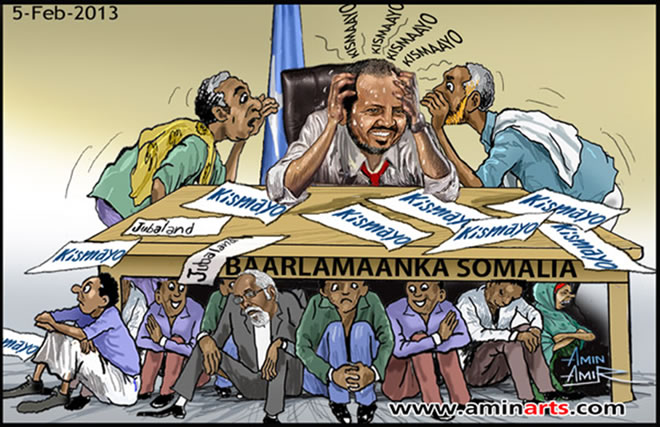

Look, have you ever tried to hear what your friends are saying in the middle of a packed market when it’s bustling with people? In that moment, the market is sending amalgam of voices (noises) and it’s interfering with your ability to hear clearly the message (signal) you want to hear. Now understand that the noise is the unwanted energy that is interfering with the wanted signal. That is what Kismaayo is to the Somali government: too much noise but the government can’t still figure the signal.

Abdi Aynte, the founder and the executive director of the Heritage Institute for Policy Studies, wrote awhile back giving a good picture of the situation of Kismaayo: “At the center of the Kismaayo conundrum is a rancorous clash of two narratives. A Kenyan-backed armed group that recently captured the port city from al-Shabaab fighters wants to unilaterally decide the fate of the city and, ultimately, form a regional administration called ‘Jubbaland’.” Aynte continues, “But the new Mogadishu-based government wants to shape the administration of Kismaayo as well as the future regional state.” However, what happen in Kismaayo this week shows that Aynte’s analysis is half of the picture and the other half is the clannish roots of Kismaayo’s wars (we Somalis know what happen Kismaayo this week has little to do with so-called government forces, and everything to do with Kenya’s influence in the region, and the city’s clannish war history).

In the late 90s and even before Al-Shabaab appeared, Kismaayo comparing to other cities in Somalia, more often was the center of continues turmoil, and it forced many groups in different times, including President Abdi Qassim and Yusuf’s governments to take on sides. The center of the problem was then and still is, who governs the Port City of Kismayo. But now you have to add three more problems in that old equation: Kenya and Ethiopia using IGAD as proxy plus X’s (the unknowns: influence by other characters who have shady agendas that is unknown to most of us). This delicate situation requires a thoughtful thinking, bold, and swift move before it escalates into something far worse, something that will eventually threaten the existence of the current government.

The solution is politics based on practical reality that has no tribal or ideological motives that will use force if it’s deemed necessary for the greater good. Again, there are those who say dividing Somalia between tribal territories is not good, and those others who are proposing Jubbaland State as a comprehensive solution for Kismaayo’s enigma. But what these two groups are proposing is not practical and convenient at the moment for different reasons, the prime reasons being the current unfolding of Kismaayo, and Somalia’s current situation (it is a matter of life and death, and if tribal lines could help, then be it for the time being). Nevertheless, the responsibility and the legitimate authority to make the city habitable and peaceful resides with the central government and the genuine locals.

The late British Colonel George Henderson said, “it’s hardly possible to discuss the spirit of any army apart from that of its commander. If in strategy a wholly, and tactics in great part, success emanates from a single brain [as the case of Somalia, the leadership].” President Hassan and his Prime minister are blinded by the fact that more than 20 countries have deployed envoys to Somalia in the last five months, apparently giving the central government a short reassuring of legitimacy and power. The fact is these envoys come for their own interests, and will soon run away when they smell trouble in the horizon. The ultimate losers will not be these envoys and their governments, but the President Hassan’s legitimacy and his integrity before the Somali people, Somalis, and the new Somali government.

Power, in order to bring a lasting solution, we must understand both its gentle and coercive components. Although these two parts are contrasting, they both are the core of power, and one can’t understand and use power properly without understanding the purpose functional of these two parts. Kismaayo’s solution demands both power components: the carrot (gentle) and the stick (the coercive). For example, in 1870, the Franco-Prussian war broke out between the current modern States of France and Germany -- German’s aim being to use the war as an instrument to waken German nationality and to unify German states (different warlords ruled Germany at the time). Otto von Bismarck, then the Prussian Chancellor, said later, "I knew that a Franco–Prussian war must take place before a united Germany was formed." But here is the master-stroke, Bismarck knew the goal wasn’t to conquer France but rather to take what he deemed as Germanic territories and then offer peace to the French which he did. Decades later, after the WWII and the death of President Roosevelt, Churchill then the Prime minister of England, tried to convince President Harry Truman to wage war against the Soviet Union. But Truman understanding the consequence of such war ignored Churchill’s madness. Both Truman and Bismarck understood the components of power, when to wage and when not to, and the limits of leadership while keeping eye on the big picture: the future of their respective nations. President Hassan isn’t less smart, less courageous, or less pragmatic than those leaders, and he should not forget the forces that are at play covertly before his eyes.

In early 2000s, Somalia’s pirates become a global problem costing billions to the international community to combat piracy and alerting nations to the spillover of Somali problems outside its borders in addition of being a safe-haven for some of the most wanted Al-Qaeda members as was said. In 2005, the CIA turned to Mogadishu’s warlords for help to capture people they suspected of working with/for Al-Qaeda. This plan gave birth to the Alliance for the Restoration of Peace and Counterterrorism, and it backfired by uniting what was later called, the Union of Islamic Courts (the mother of Al-Shabaab). As Western strategists said then, a weak Somali government was inevitable and necessary to combat both what they considered extremists and piracy. Consequently, outside powers started funding more money to Somalia’s cause, changing their policies toward Somalia and forcing local Somali leaders to come to the negotiation table. In 2008, the UN adapted resolution 1816 to combat piracy in and around the Somali coast. Today both piracy and Al-Shabaab extremists are slowly becoming stuff-of-the-past, and soon those countries funding AMISOM mission in Somalia will change their strategies in order to make the Somali government impotent and permanently dependent of their help: more food aid. This will not serve the best interest of Somalia, and that is why Kismaayo problem shouldn’t be viewed as a minor problem but a national security matter that must be solved swiftly even if the action demands ignoring what the constitution says about self-determination regarding to local state establishments.

The reality is, there are many ways to fail and succeed, and there are few cards left on the table that could be used to solve the Kismaayo puzzle. Yet, we have to remember the words of an Italian strategist and historian, Niccolò Machiavelli, who said, “that there is nothing more difficult to plan, more uncertain of success, or more dangerous to manage than the establishment of a new order of government,” thus we have to be prepared to use different tactics when they’re most useful. As the Chinese philosopher and war strategist, Sun Tzu, said long time ago, that “the [leader] who thoroughly understands the advantage that accompany variations of tactics, knows how to handle his troops.” One of the cards is by making the city of Kismaayo itself a city-state while abandoning the idea of Jubbaland completely. Consequently directing Garbahaarey and Dhoobley to start forming their respective governments; otherwise, appeasing those who disregard the nation’s interests will not change a bit if recent Somali history is our guide. It will be foolish, timid and stupid move insisting on appeasing these bloody men.

Don’t let the city of Kismaayo to hold hostage other regions in Jubbaland like Mogadishu did to the rest of Somalia since 1991 with the exception of Somaliland, and Puntland since 1998.

The other card is implicating Kenya for her hand in Jubbaland scheme and expelling its soldiers from the region; finally forcing the combating tribal rivals to submit to the Federal government’s whip by hook-or-by-crook (Al-Shabaab’s power governing style), and thus forming a temporary government for Jubbaland region until later date. Indeed, we could say the assessment of the situation of Kismaayo today by a former Al-Shabaab governor, Sheikh Yakub, is closer to the truth then others would like to admit.

Former US Secretary of the State, Kissinger, remarked during the World Economic Forum in Davos this year that “the challenge is of moving the world from where it’s, to where it has not yet been and that requires vision and idealism.” Somalis, our idealism and vision, at least most of us, as an old Somali elder once told to the late British colonial soldier and author, Gerald Hanley, in his book: Warriors: Life and Death Among the Somalis, when he asked the old man’s wish in early 1940s before Somalia had a government, the old man replied, is “to be well governed and left alone.” Think about it. Isn’t that what we all want? At the end, we all have that nomadic gene within us that thrives on freedom and detests injustice. Some of us view the problem of Kismaayo/Jubbaland on tribal lenses, others under regional microscope, and few from a nationalistic angle. But we all agree that Kismaayo should be left alone to the Somalis to decide its fate, and ultimately, among us, one group will make that call. Not all of us will have a say whether we like it or not, and no group is better positioned than the central government to spear head the process. Somalis, what’s at stake is our own survival and unity, and rules must be bended as situations change for the greater good of the nation: the constitution isn’t higher than the Quran. At the end, we all want to be well governed and left alone, and our challenge is moving forward intact as a nation: everything else is just a noise distracting our leaders from the big picture.

Hassan Mire

Studies Economics and Global Studies at University of Wisconsin

[email protected]