Thursday December 14, 2023

By NATASHA HAKIMI ZAPATA

Uganda’s role as a co-convenor of the Global Refugee Forum in Geneva this week should raise urgent questions about the interests behind its much-lauded open-door refugee policy.

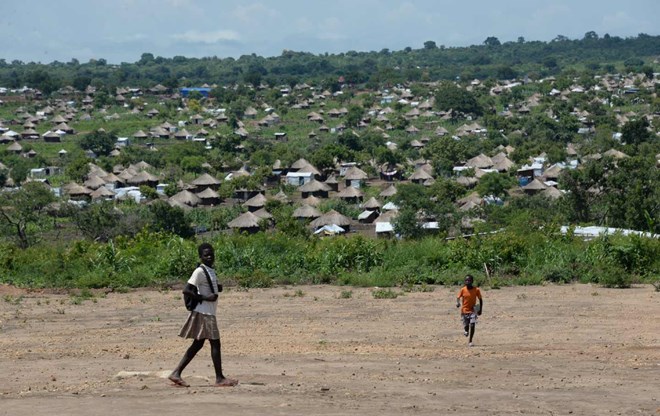

Children walk along a road in the Bidi Bidi refugee settlement in northwestern Uganda. (Gioia Forster / Picture Alliance via Getty)

KAMPALA—“I’m barely surviving in Uganda, but I am still alive,” says a refugee from the Democratic Republic of Congo whom I’ll call Joseph, as goats and chickens scuttle through Kampala’s informal settlements. Over several weeks, refugees from the DRC, Somalia, South Sudan, Burundi, Rwanda, Eritrea, and Afghanistan, among other countries, each told The Nation their stories of displacement to Uganda, a co-convenor of the United Nations’ upcoming 2023 Global Refugee Forum. Most ended on a similar note: We are struggling, even starving, but we are safe.

At the Geneva forum beginning December 15, this East African country and temporary home to 2.4 million refugees will be showcasing what is known as the “Uganda Model” for refugee-hosting based on its 2006 Refugee Act—hailed time and again by the United Nations and Western media as the most progressive in the world. And yet, while humanitarian and refugees groups recognize that Uganda’s approach is indeed progressive, the refugees’ increasingly dire circumstances amid aid cuts and failed strategies should be raising urgent questions about why the West is so invested in holding up Uganda as a model to the rest of the world. So, too, should President Yoweri Museveni’s growing authoritarianism. Could it be, as some critics have suggested, that the West is willing to overlook both poor conditions in settlements and Museveni’s dangerous power grabs in order to prevent refugees from reaching our own shores?

Uganda’s refugee status adjudication process is also far more straightforward than most—and has been expedited for those fleeing neighboring South Sudan or Democratic Republic of Congo thanks to prima facie designation that recognizes the ongoing conflicts in both countries as the source of displacement. As for its “open door” approach, Ugandans say this is grounded in a Pan-Africanism that even their president for the past 37 years espouses. Like many of his fellow Ugandans, Museveni himself was displaced during Idi Amin’s rule, an experience that, to many in East Africa, drove home the fact that anyone can become a refugee.

“Sometimes the West lacks a humane approach,” says Refugee Commissioner Douglas Asiimwe, using the ancient African term ubuntu, meaning “humane.” “These are our neighbors; they are running away. What do you do? Close the door? No.”

Unlike most refugee-hosting countries, Uganda practices a settlement approach rather than a camp or detention model. As such, refugees can move freely around settlements as well as in and out of neighboring towns and cities.

In Bidi Bidi—the largest refugee settlement in Africa and second-biggest in the world—it’s difficult to tell where the town of Yumbe ends and the refugee settlement begins. Teetering on the border with South Sudan and just a few miles from DRC, Bidi Bidi has practically become a city in its own right, hosting markets brimming with stalls run by Ugandans and refugees selling street food like rolexes (the street food, not the watch), cleaning products, and other essentials. It is also peppered with dozens of schools and health centers—many of which are being turned into permanent structures—all of which serve the hundreds of thousands of residents living in clusters of round mud houses with grass-thatched roofs built by refugees themselves on the 30m by 30m (98ft by 98ft) plots they were allocated for housing and subsistence farming.

In 2016, turmoil in South Sudan put Uganda’s refugee policies to a test no one in the country had foreseen. The East African nation of under 39 million went from hosting half a million refugees in 2016 to 1.3 million in a matter of months. South Sudanese radio journalist Christine Onzia Wani, who’s lived in Bidi Bidi for the better part of a decade, says that as civil war broke out again in South Sudan that year, she and her husband refused to believe their eyes.

“The war started like a joke,” the 34-year-old tells The Nation as her son feeds their goat nearby. “By the time we decided to leave, we almost [had to make] the journey on foot, but we took a very difficult decision to sell one of our most valuable possessions just to get a barely functioning car to take us to Uganda.”

Most South Sudanese refugees fled to the underserved West Nile sub-region, where many still remembered their own displacement to modern-day South Sudan and elsewhere due to Uganda’s own decades-long civil war. The United Nations Refugee Agency scrambled to provide refugees with white tarpaulins, solar panels, and other basic equipment and urgently set up infrastructure with partner agencies and Uganda’s Office of the Prime Minister. But more often than not, locals became the first responders, opening their homes and lending out the land Bidi Bidi is built on—owned by local Aringa tribes—to house their neighbors in their time of need.