The Sun

Friday October 1, 2021

When Shugri Said Salh was six years old, she was sent to live with her grandmother. This would not be so unusual, except that Salh’s beloved grandma, or ayeeyo, was a nomad. Salh was pulled out of school and made to leave the city life of Galkayo in Somalia behind.

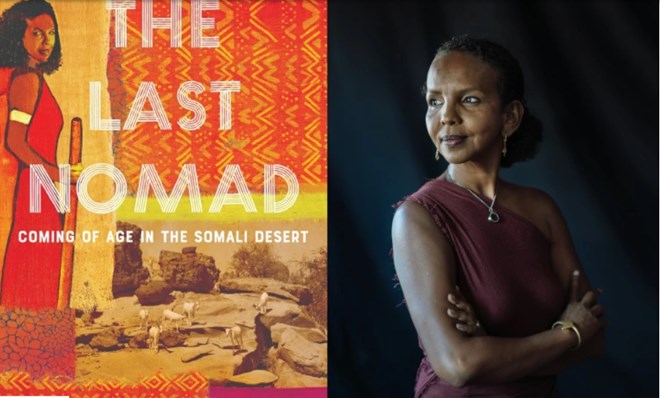

Salh, now a successful infusion nurse in Sonoma County with a stable marriage and three children, uses this moment as the jumping-off point for her memoir, “The Last Nomad,” out now from Algonquin Books.

“I always knew I had to tell my life story, which is unusual even for Somalis,” says Salh, who is warm and friendly in conversation.

It’s a unique story of an unusual life — one that taught Salh about the beauty and the perils of the nomadic existence before she returned to the city and her domineering and abusive father, who had abandoned the wandering life to build a home and become a teacher. Even after leaving her grandmother behind, Salh remained a nomad for years, living in orphanages and with different relatives, fleeing during Somalia’s civil war, first to a refugee camp, then to Kenya and finally to Canada. But even there, life was unsettled due to her physically abusive older sister, whose violent outbursts forced Salh to resume wandering.

The book recounts the parts of her childhood she savored, from her relationship with her wise and poetic grandmother to her explorations of the natural world. Today, she still revels in nature, frequently finding her peace in hiking, whether alone or with friends or family. It also, she says, made her a “mean mom,” who strictly limited everything from TV to social media for her kids.

That said, she acknowledges that her current lifestyle means she could not go back to being a nomad. “I’m a nurse and would freak out and want to scrub everything,” she says. “That world was filled with risk and life was dispensable there. Now I’m a different person. I’m loving my children, my husband, my community. So life is no longer dispensable.”

The book digs deeply into the parts of the Somali culture that she found dark and destructive.

“The clan system is really bad in Somalia,” she says. “Somalis can extend great kindness but will also kill each other in the name of clan. Even now on Facebook, it can get to be too much where people get so intense and obsessed with who is from what clan.”

She also pushes back against nationalist sentiments. Salh’s husband is Ethiopian, “supposedly our enemy.” She says her willingness to see beyond those boundaries has stirred up trouble in her family since childhood.

Salh also addresses the issues of female genital mutilation, which she describes in detail in the book, explaining the horrors and the long-used justifications. “If I don’t give you those insights into that world, how can you understand,” she says.

Salh, who underwent the excruciating procedure, emphasizes that doesn’t see herself as a victim nor does she blame her grandmother for doing it, given the culture of the country at the time. Had she resisted, Salh says, she would have been abused and ostracized.

“My grandmother was doing me a favor — and I would not have been this confident woman you see now,” she says, though of course, she is glad that her Californian daughters grew up free of the practice, not even knowing such a thing exists. “How beautiful that is when they say, ‘What are you talking about, mom?’”

While she would like to return home, Salh says the violence of the Somalia-based extremist terrorist group Al-Shabab prevents her from returning to her homeland to find closure with her past.

“I feel the loss of my people and my culture and the disenfranchisement of my people,” she says. “I know that it’s very risky to go back especially if I don’t cover myself. The idea that Al-Shabab could get a hold of me and decide my fate leaves a visceral, physical pain in my body. Do I need to spend $20,000 for my safety or go incognito and wear a burqa?”

Still, despite the real danger, she longs to return. “My yearning to return is so deep that it may overcome my fear.”

Salh has found some measure of peace by confronting her past in a more intimate way, by breaking with Somali tradition and airing her family’s darker secrets in the memoir, especially the abuse she suffered at the hands of a family member.

“Somalis never talk about these things and the book took longer to finish because I deleted that section nine times,” she says, before adding that she also left out other incidents that were equally awful.

Salh is glad that she told her truth. “Writing this memoir was very cathartic,” she says. “I used to have nightmares all the time about all the traumas that happened to my body. Now the nightmares have gone away.”