Wednesday June 12, 2019

By Abdi Latif Dahir

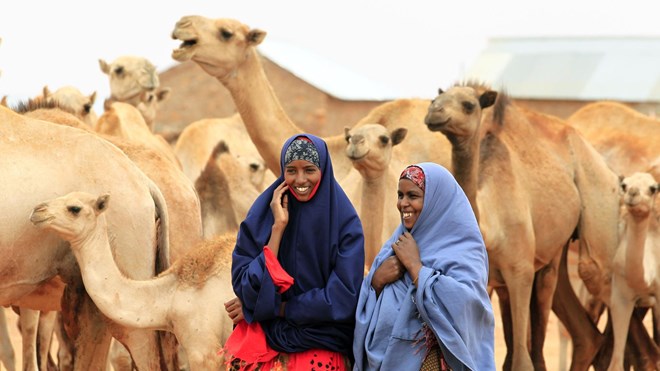

Supplying from camel to cup./REUTERS/THOMAS MUKOYA

For the first time ever, residents of Glasgow were in late May treated to a cuppa with a twist: cappuccinos made from camel milk. The Willow Tea Rooms in the Scottish city introduced the new coffee drink as part of a project to support Kenyan female milk traders who are battling climate change in Wajir county located in the nation’s northeast.

With more than 12.2 million heads of camel, East Africa is home to some of the world’s largest camel populations. Rich in iron, vitamin B and C, and low in fat, the frothy milk produced by the hunched mammal is valued in the region and across the world for its medicinal value—particularly against diabetes and allergies—and is even used as an aphrodisiac. It’s also prized as a source of nutrition especially in hot and arid zones where climate change is exacerbating drought conditions and decimating food chains.

As such, camel dairy products ranging from baby milk to chocolate bars, pizzas to frappuccinos have been launched all across the world. In Africa, enterprises like Mauritania’s Tiviski have been successful in disrupting the milk industry, ensuring they buy from local camel herders instead of relying on milk imports. In Chad, milk bars are helping popularize the consumption of the slightly salty milk, while Egypt’s Tayyiba Farms offers a range of products including camel white cheese, kefir, and yogurt.

Yet across East Africa, the camel dairy business remains rudimentary with much of it being sold and consumed in domestic markets or guzzled by young camels themselves. This underutilization of the creamy liquid, some say, undermines its potential to grow into a multi-billion-dollar business that could change the lives of herders and milk traders alike. Given its benefits for health and well-being, camel milk could grow to become the next global superfood attracting health-conscious consumers.

“No one’s talking about it,” says Bashir Warsame, whose camel processing firm Nuug opened in Nairobi last year. Warsame sources from herders in the southern and central towns of Voi and Isiolo respectively, delivering both camel milk and yogurt in various flavors to supermarkets and homes in the Kenyan capital.

“The camel industry is very virgin from the milking stage to the delivery.”

Pouring camel milk in Mogadishu, Somalia.

Warsame is one of a new crop of entrepreneurs who are tapping into what some have called the “white gold.” Using a blend of direct marketing, social media, and word of mouth, their aim is to bring the desert animal into cities and realize the commercial value of camels. They are also changing the consumption of camel milk from its usual smoked and boiled usage and introducing it in pasteurized and powdered forms.

These include companies like White Gold, which kickstarted operations in the central town of Nanyuki after the giant camel milk firm Vital faced financial woes and ceased operations in 2017. In Wajir, non-governmental organizations like Mercy Corps have also helped install refrigerated ATMs, allowing traders to keep the milk from going sour and deliver it fresh. To boost the camel population and enhance food security, Kenyan officials have also distributed camels to pastoralists in arid and semi-arid areas.

Camels being exported from Somalia to the Middle East.

In Somalia, which has one of the highest numbers of camels worldwide, camel dairy production is also being looked into as a profitable business that can integrate pastoralists into the formal economy.

“I do truly believe camel milk to be a superfood and more importantly the milk of the future,” says the founder of the Sweden-based startup Agrikaab, Mohamed Jimale.

From Ethiopia’s teff to Senegal’s fonio, the baobab, tamarind, and dried hibiscus, Africa has contributed to the global explosion of superfoods which have drawn many Western customers due to their high content of nutrients and antioxidants.

As a former nomad himself, Jimale started his firm in a bid to improve Somalia’s livestock and agricultural sectors—both hampered by recurring droughts and water scarcity. Besides using cash to sell camels to both locals and foreigners, Agrikaab also accepts cryptocurrencies in a bid to attract more customers.

Barack Obama as a senator in 2006 visiting Wajir town in northeastern Kenya.

With six active farms across Somalia, two of which are dedicated to camels, Jimale says they hope to strike partnerships that could help them manufacture products like camel milk cheese, ice cream, and soaps.

Nuug’s Warsame says he’s looking at the possibility of making camel milk cosmetics—a beauty regimen possibly first realized by Egyptian queen Cleopatra who is reputed to have bathed in camel milk to maintain soft and clear skin.

Before this is attained, a number of barriers related to sourcing, infrastructure, and marketing will have to be resolved. Warsame says one way to mainstream camel milk is to marry it into the local coffee and tea scenes—which is being exported worldwide from countries like Ethiopia. Governments, he says, should also integrate the camel and pastoralist culture into the tourism industry.

“It’s all about being creative with this raw material that’s abundantly available,” he said.