Tuesday July 9, 2019

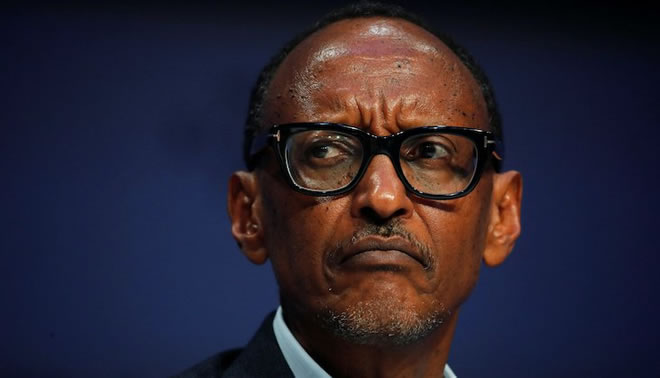

Rwanda's President Paul Kagame granted The Africa Report a long interview following the Africa CEO Forum, in late March. In part one, he gives his views on industrial policy, regional integration and the failure of the Western model of the past two decades. Presented here is a transcript, with light editing for clarity.

The Africa Report: One of the themes that seems to cut across both Africa and Europe in recent years is inequality driving political upheaval.

President Paul Kagame: Everyone is worried about it, and it really is [present] all across the world. In Rwanda, you may also find inequality but we have been reducing this inequality in the past 10-15 years, narrowing it. And I keep telling people, even in our own discussions or in discussions outside, sometimes they think of inequality wrongly or blame things on inequality in a wrong way.

So people may say: “Look at Kigali, the way it is moving so fast. But how about rural areas?”

My starting point is the people at the lowest level. I look back and say: “How many did we have in abject poverty, what was the situation 20 years ago? So looking at numbers, how far up have we gone? Are we making a difference in terms of equality but also numbers of people being affected. Yes or no? Can we move these people out of this level of poverty faster? Yes or no?” So what are the tools we have? What can we do? And then we do that.

So what we have found is that a majority have been moved from the lowest to some [higher] level. Still, even by districts, you will find some districts have done better than others.

And if you look at this city [Kigali] as you move around and make inquiries, the industries here or these buildings you see here are mainly built from within and most of them are Rwandan investments.

We were recently trying to imagine what could be an East African version of Airbus. Tanzanian entrepreneur Ali Mufuruki said: “The problem is you can’t meet Chinese demands in Rwanda. But what about creating an East African coffee brand where you not only have the very best grade coffee but you’ll be able to provide a lot more?” Might something like this be useful, analogous to the coal and steel boards that preceded the European Union?

I completely agree with the assertion. If we built something like that and it benefits East Africa at the same time, meeting the big demand [from China], that would be the ideal situation, absolutely. I mean it’s very clear.

But that only happens if you address many other problems. I have always thought that in most of these cases nothing is so independent of the other – the economics, the business will not be independent of the politics, and the politics is not completely independent of the economics of business, in fact they help [each] other in a very clear way.

We are still stuck in very old politics, if I may say, and we are stuck there even when we are aware that there are more and better things we can achieve together, but still we take this route that’s old-fashioned or archaic. Because integration necessarily means give and take, it means giving away a certain level of countries’ sovereignty. At the same time, the old politics plays on sovereignty as if it’s the beginning and the end of everything.

Trying to fight that way of doing things is what we are trying to do [in pushing] through reforms in the African Union. It’s not just one region, it’s the whole thinking about our continent. And when we are together in the room – 30-40 heads of state and the government, 50 sometimes – you know you tend to say: “Okay like we are here together in this room, why don’t we act together like we are here in this room?” And the benefits are obvious to all of us, but when we separate from the general assembly hall then we continue to be individuals again.

So it’s something not one individual, one country can [do]. You can do your part in your country, like some countries are trying to do, but when it comes to that step where we have to do it with others, [we] fall very short.

But as a national leader – and you’ve had 25 years – you must have had a very strong sense of Rwanda’s national interest. Isn’t your first and foremost obligation to your national population? How you go from there to even within East Africa, let alone the other 55 countries?

How we go from that is, in a way, simple, because I start from a point where theoretically everybody seems to understand that. I’ll give you two examples – there are many more. We have discussed with the Volkswagen leadership that we want to make this investment an East African thing. Let each one of our countries have something to supply to Volkswagen.

One country supplies tyres; another one pieces of the car. And in fact, for us, because Volkswagen are going to provide what they call mobility solutions and they are going towards even building driverless cars and so on – which will need high connectivity internet and stuff like that – and they preferred Rwanda because of the connectivity here, that could be our part we should concentrate on. And we said fine, we are happy to concentrate on this, bring in others to provide other parts of the car, which was the point you are making earlier about Airbus.

A second aspect, slightly different from that but which complements it: as you are aware, we are the first country in Africa that started allowing Africans to travel to Rwanda. We said all Africans. Some of them don’t need a visa, others will just get a visa on arrival. And we said all without exception, and we started campaigning around that and showing our colleagues across the continent that much as you think there are problems associated with this, we haven’t found any problems going this route so far, two years [on].

Isn’t there like a fundamental tension between the industrial policy that a country might want to have and a regional approach? If you start to have an economic federation, those tools of industrial policy get taken away, as we’ve seen in southern Europe – they don’t have monetary policy in the same way with the euro and they are struggling, Greece is struggling.

But I think both Europe and China – but more so with China – they have an advantage of some kind. China is really one entity more or less, it doesn’t have this [aspect of] small independent states coming together. It is one block, so that becomes easier, much as it’s a huge population, 1.4 billion people.

Europe also has an advantage, as much as they may face problems, as we’ve seen. Its systems are advanced, like the European Parliament, for example: you actually have parties of different European countries forming almost one party, one party in Germany collaborates with another party in this [country], there’s conservatives across Europe, liberals, etc.

So that helps, in a way. It doesn’t answer every problem that may arise, but it’s something important. So the building up to the regional parliament is a bit easier than [it would be] if we tried it now, and we have built up to that. Because it allows these conversations, discussions, comparing notes across this geographical space.

In Africa, and let me talk about East Africa for example, the political structures of parties, of parliaments and so on are completely fragmented. So when you bring this number of parliamentarians from one country, then from another, the main commonality has been that you come from Rwanda or you come from Kenya. It’s not that my party and yours are more or less the same and we have these relationships. So when we go to this parliament, it has a problem in the final outlook of what you have to do.

But that’s fine, still it is better than not having it. It’s a step forward. So the failures will come when these paths are not followed carefully. Again, we have our own problems in East Africa, in that sometimes the project of integration has come about as a result of leaders sitting in this room and saying integration is right, but they forget to mobilise their people to be part of it.

So we’ve got this wave – you can see it in Europe clearly, you can see it in America – it’s nationalism, parochialism, ethno-nationalism in fact, across Europe: populists’ policies being pushed for short-term benefits, a lot of finger pointing, blaming minorities. What you were trying to do at the African Union – and now you’re chairman of the East African Community as well – seems to be going against the grain in a way. Do you think Africa is on a different trajectory to Europe? While we have this growing nationalism on a global level, what Africa is trying to do is to bring these countries together, to have a federation that works and create more of an African identity than just a Rwandan or a Kenyan identity. Do you feel you are swimming against the global tide at the moment?

Actually, it’s very ironic in a sense, and the level of cynicism as well. You see what Europe started doing and it went to the level where they thought – let me call it the West actually – they thought this system they have created is the best in the world, everybody should follow. So everybody has been struggling to follow, especially Africa, to cope with the system, the dictates in the system by the West [who say]: “Africa, we measure the progress you are making against what we have created.”

As we try to struggle to follow what has been created, now what has been put before us is sort of crumbling.

It’s crumbling, so that leads us to the other issue which is that for 10-20 years that was the model that worked: the Berlin Wall went down, free market capitalism, liberal democracy was meant to rule the world – [Francis] Fukuyama, The End of History and everything. Now, 25-30 years later, it clearly isn’t ending and there are several other models, competing models.

The industrial revolution stated with James Watt in Britain in the early 18th century. I don’t think you want to spend 250 years industrialising Rwanda. You’ve got a programme, you’re talking about becoming a middle-income country by next year, in fact. So how are you navigating between what you said is the crumbling Western model and – in terms of economics at least – a much tougher, more successful Chinese model?

In fact, that’s a very good point, but it’s also a good point in a sense that we are in an era where there are these difficulties across the world, but they constitute the best opportunities for us, for Africa – the best we’ve ever had.

This navigating is actually the best thing for us. Because you can try to get the best from whichever side you may choose and what you think may work best for you – you are not tied to one thing, whether it is good or bad. You are now having freedom. That navigation, it means freedom, freedom to navigate, making choices between so many things.

Click here to read this article from its original posting