By Miriam Berger

Thursday December 12, 2019

Demonstrators shout slogans during a protest against the arrest of three prominent activists for press freedom, in central Istanbul,Turkey, June 21, 2016. REUTERS/Osman Orsal

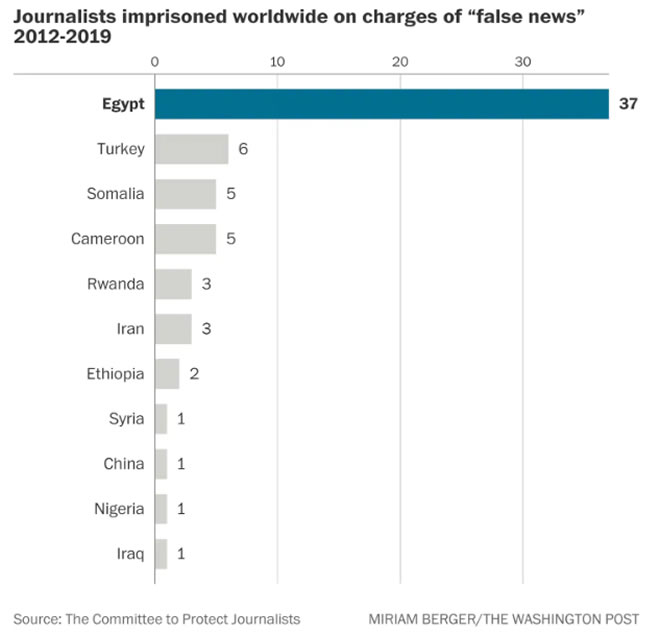

As 2019 draws to a close, there are 30 journalists in jail worldwide on charges of “false news” — or, as it’s also called these days, “fake news.”

It has now become commonplace to throw around fake-news accusations in the United States. But in other countries around the world — like Egypt, Turkey, Somalia and Cameroon — such charges can have very chilling and stifling impacts on the press, according to an annual report by the New York-based Committee to Protect Journalists.

In Egypt — where General-turned-President Abdel Fatah al-Sissi has been overseeing a crackdown that human rights groups say is harsher than any before — there are 21 journalists in jail for allegedly publishing “false news,” according to the CPJ’s data. In practice, press freedom advocates say, these charges stem from a simple fact: The journalists published news that Sisi didn’t like.

In Cameroon, where English-speaking separatists are fighting for independence from the mainly French-speaking government, five journalists are in jail on these charges. Many more have been detained on similar grounds for their reports on the conflict.

It wasn’t this way five years ago, said Courtney Radsch, advocacy director of the CPJ, which tracks these trends.

In 2012, there was just one journalist in jail on fake-news charges. By 2014, there were eight. Then came 2016, when the most dramatic rise began, in which 16 journalists worldwide were in jail on fake-news charges. The number rose to 27 in jail by the end of last year.

Overall, between 2012 and 2019, there have been 65 journalists imprisoned on false-news charges. For comparison, since 1992, when the CPJ started tracking the trend, an overall 120 journalists have at one point been locked up for spreading so-called fake news. That means more than half of the journalists jailed on these charges were in prison sometime in the past seven years.

Radsch attributed the rise in part to the spread of the Internet, which upended traditional means for governments to stifle the press, such as direct censorship of newsprint and controls over media licenses. As a result, many more countries have enacted laws around fake news as a way to exert pressure on and control what information is published and shared online.

In October, Malaysia repealed a 2018 law criminalizing fake news following criticism that it was really a front for curbing dissent. In November, Singapore for the first time invoked its fake-news law to force a citizen to amend a Facebook post claiming that the government invested in a failed restaurant project. Also in November, protests erupted in Nigeria against a draft law that would allow police to “arrest people whose posts are thought to threaten national security, sway elections or ‘diminish public confidence’ in the government, according to the draft text,” as The Washington Post’s Danielle Paquette reported.

Radsch also attributed the spread of these laws and arrests to “the permissive environment created by the rhetoric around fake news” and in particular how “the usage of the term ‘fake news’ by President Trump has reverberated around the world.”

Egypt had laws against false news already on the books “before it became the favorite way of targeting journalists” in the past few years, Radsch said.

Now Sisi — whom Trump called his “favorite dictator” — has overseen the expansion of the law to criminalize commonplace journalistic practices that serve as a check on the state. For example, journalists who publish information about the military other than what the government provides them can now find themselves locked up and branded as “fake news.”

There is a serious global problem of disinformation spreading online and sowing distrust and sectarianism. The problem, say press advocates, is that the laws regulating fake news all too often are a means of stifling the media rather than fostering a more transparent environment online.