Saturday March 31, 2018

Ryan Devereaux

Guled Muhumed and his daughter Aysha Guled Ahem. Photo: Courtesy Laila Jama

When Guled Muhumed boarded his flight from San Antonio to El Paso, Texas, on Monday, he noticed something unusual. The 32-year-old Somali national and longtime U.S. resident was en route to his 10th immigrant detention facility since Immigration and Customs Enforcement officers arrested him on the streets of Rochester, Minnesota, on September 29, 2017, as he drove his 17-month-old daughter to day care.

During his six months in custody, Muhumed estimated that he had been a passenger on about a half dozen ICE flights. Typically, he said, those flights featured one ICE officer and a handful of contractors. Monday was different.

Inside the plane, Muhumed noticed approximately seven men in uniforms bearing insignia that read, “SRT.” The so-called Special Response Teams are an ICE tactical unit. Described on the agency’s website as elite, highly trained operators, SRTs are tasked with taking into custody and deporting “hardened criminals, such as drug cartel and violent gang members,” ICE’s “highest priorities for arrest and removal.”

Once Muhumed’s plane touched down in San Antonio, he and the dozens of other African immigrants he was flying with began exiting the aircraft. On the runway, they were greeted with another contingent of SRT officers — except these ones, Muhumed says, were decked out in what he calls “military gear: helmets, guns, bulletproof vests.”

Shackled in chains, Muhumed and the other detainees shuffled off the plane and were passed by their hands from one heavily armed SRT officer to the next. There was no doubt in Muhumed’s mind what the ramped-up security was all about. “Whatever they told you, it’s not true,” he recalled telling one of the SRT officers before his flight landed.

Muhumed is one of 30 Somali men who say they were subjected to a horrifying week of abuse at a for-profit immigrant detention center in Texas last month. Their allegations, which included claims of physical and sexual abuse, as well racial slurs, were detailed in a chilling report published last week.

As The Intercept reported last weekend, those allegations resulted in complaints filed with the Department of Homeland Security and the Justice Department, accusing ICE’s contractors of multiple violations of federal law, including hate crimes, which were forwarded to the FBI.

ICE has refused to confirm whether it has opened an investigation into what happened at the West Texas Detention Facility, a for-profit operation run by LaSalle Corrections. Similarly, ICE has refused to address the ramped-up security Muhumed described witnessing during his transportation on Monday. In response to a series of questions sent Wednesday, a spokesperson for the agency instead pointed to general ICE policy on a range of issues without clarifying if, how, or why those policies were being implemented in the case of Muhumed and his fellow detainees specifically. LaSalle Corrections has not responded to requests for comment since the allegations came to light.

In the week since the reported abuse was made public, advocates for the men told The Intercept that oversight officials from DHS conducted interviews with the individuals named in the report.

In interviews this week, Muhumed recounted his experiences in West Texas, and the terror he has been living through, faced with the serious possibility of being separated from his wife and children and dropped off in a war-ravaged nation that he has not seen since he was a child.

Muhumed also described the anguish of watching mistakes he made when he was a young man come back around more than a decade later to wreak havoc on his adult life. As a high school administrator and youth counselor, Muhumed spearheaded a program in his community to turn refugee children, particularly young Somalis, away from drugs, crime, and radicalism. He has spoken out publicly against the terrorist groups that wield considerable power in Somalia, making the fact that the U.S. government has treated him like some sort of national security threat, while working hard to drop him off on the very turf where those groups operate, all the more ironic and terrifying.

Laila Jama, Muhumed’s wife, who also came to the U.S. as a refugee child from Somalia but eventually won her citizenship, is pregnant with twins and due to give birth in the next two weeks. She described to me how, over the last six months, she has made herself an expert on immigration law. That education, she said, has led her to conclude that the U.S. system of detention and deportation, when applied without discretion, is unfathomably harsh, especially if you come from an African country like Somalia.

The family’s account, bolstered by legal records and testimonials on Muhumed’s behalf, as well as prior reporting, suggests that ICE and the Trump administration may be taking a particularly hardline approach against immigrants of African descent, especially Somalis. Fraught with logistical challenges, that effort has resulted in men like Muhumed being shuffled from one disaster of a detention center to another as they await their banishment from the only country many of them have ever known.

Arrested on the Way to School

Early one Friday morning, last September, when Muhumed was driving his daughter to day care, he noticed what appeared to be three unmarked law enforcement vehicles tailing him. He was approximately one block from home when he was pulled over.

Muhumed recalled one of the officers approaching his vehicle with his gun drawn. His mind raced with the stories of black men shot dead during traffic stops. It had been just a little over a year since a Minnesota police officer shot and killed Philando Castile during one such stop. Castile was Muhumed’s age and, like Muhumed, was a beloved figure at the school where he worked. Muhumed immediately placed his hands on his steering wheel and awaited orders from the officers.

Unlike Castile’s fatal encounter, Muhumed said he could tell the officers stopping him were not local cops. Dressed in khakis, something told him they were with ICE. Once out of the car, Muhumed was placed in handcuffs. It was then, he said, that his daughter began to cry. He pleaded with the officers to allow him to sit in the backseat to calm her down while they waited for his wife.

By the time Jama arrived, Muhumed was already being loaded into a van. He claims he had asked the ICE officers for 15 minutes to say goodbye, and they had agreed to do so, but when Jama got there, they reneged on the request.

As the van drove off, leaving his wife and daughter behind, Muhumed saw more than 20 years of life in the U.S. slipping away. “At that moment, I left my wife crying and my daughter crying,” Muhumed told me. “It was heartbreaking.”

Muhumed and his family were admitted to the country as refugees in 1996, after fleeing the devastating civil war that broke out in Somalia in 1991 and after years living in refugee camps in neighboring Kenya. They first landed in Atlanta, Georgia, where Muhumed attended elementary, junior high, and high school before moving to Minnesota. Growing up, Muhumed says, he assumed he was an American citizen. The truth was, that while a majority of his family members were, or became, citizens, Muhumed did not.

In 2005, when Muhumed was 19 years old, he learned how fragile his status as a refugee actually was. That year, he was convicted of a third-degree drug sale. He was convicted of a second-degree drug sale two years later. As a result of those convictions, Muhumed was taken into custody by U.S. immigration officials in 2010 and spent six months in detention.

Muhumed listened as government officials told him that efforts to appeal his case would mean more months locked up. Meanwhile, fellow detainees told him that even if he accepted deportation, the U.S. would not remove him because there was no Somali government to send him to. He signed his own removal papers and was ordered to be deported to Somalia on June 15, 2010.

In both his criminal and immigration cases, Muhumed operated without a lawyer, a decision he now regrets. “I didn’t understand what that meant, signing that paper,” he said. “I didn’t know the consequence of it.”

Guled Muhumed, center, with Somali community activists in Minnesota.Photo: Courtesy Laila Jama

A Community Leader

It was a familiar American story: a young, black man from an immigrant family gets caught up on drug charges, takes a plea deal, and finds himself navigating the byzantine world of immigration courts and detention alone and without counsel. In the years that followed, Muhumed worked to turn his life around, in hopes of never finding himself hemmed up like that again — and, by several accounts, he succeeded.

Under the terms of his removal orders, Muhumed was permitted to remain in the country as long as he attended regular ICE check-ins. So for seven years, that’s what he did. “I never missed a check-in,” Muhumed said. “Either I was on time or I was very early.” Muhumed stayed out of trouble following his convictions. He paid his taxes and, he thought, his debt to society. Whenever he would move, Muhumed would update ICE with his new address. They had “everything about me,” he said. “I wasn’t someone that was hiding from them.”

In 2011, Muhumed found work at the STEM Academy, where he rose from a classroom paraprofessional to a leadership adviser overseeing and directing students on initiatives aimed at giving back to the community.

“I was made aware of Mr. Muhumed’s criminal record by one of our school board members,” wrote Dr. Bryan Rossi, the school’s director and Muhumed’s supervisor for the last four years, in a letter urging ICE to release him. “The board and the community and parents at large were supportive of giving Mr. Muhumed a ‘second chance’ and he has honored that ‘second chance’ with grace, dignity, humility and loyalty to our mission.” Rossi added that Muhumed was a “person of irreproachable character,” who showed a real skill for “being able to impact students who have trouble in school and/or the community and have difficulties being successful academically and socially. He has been outstanding as a role model especially to young men.”

Students, too, sung Muhumed’s praises in letters to ICE following his September arrest. “Thanks to Mr. Muhumed’s indomitable encouragement and motivation, it is because of him I am a proud advocate for other students who don’t have a voice,” wrote a senior at STEM Academy. “Mr. Muhumed is like a rock that holds us together and if you were to remove that, we wouldn’t be the same.” A second student added, “If his mistakes are what this is about, that doesn’t really define who he is. Everyone makes mistakes. … He is needed in our lives. His words of advice and his wisdom are needed in our community. He is loved by so many people you’d be surprised by it. I just hope you’ll reconsider things.”

Along with other Somali community leaders, Muhumed started an organization called the Somali American Youth Association. Later changed to AIM High Academy, Muhumed described the initiative as focused on service learning, sports, and mentorship, all of it part of a broader effort to provide support for refugee youth and push back against the recruitment of young people by the terrorist groups al-Shabab and the Islamic State, which Minnesota’s Somali community has struggled mightily with in recent years.

Muhumed had “worked tirelessly in the past five years to ensure our youth understands the true meaning of Islam and denounces distorted ideology,” wrote Hassan Jama, executive director of the Islamic Association of North America, in a letter calling for ICE to exercise discretion in Muhumed’s case. “Because of his work and dedications, Mr. Muhumud became a target to extremist groups, such as ‘Alshabab’ and other terror organizations.” Hassan added that he “strongly” believed that if Muhumed were deported to Somalia “he would be killed” by those groups.

Ahmed Ragab, writing on behalf of the board of Rochester’s Masjed Abubakr Al-Seddiq, echoed those concerns. “Fighting radicalization of youth in the Somali community as well as the Muslim community as a whole was one of Guled’s main areas of focus. Mr. Muhamed has organized more than six seminars in Rochester and the Twin cities by inviting Muslim scholars from around the globe,” he wrote. “Mr. Muhamed’s work in the area has made a great impact, but with that impact came the negative press.”

“The terrorist organization Al-Shabab deemed Mr. Muhamed’s views and work ‘un-Islamic.’ Mr. Muhamed received multiple threatening messages and death threats because of the seminars he has led with well-known scholars locally to fight radicalization,” Ragab added. “Sending him to Somalia will not only put his life in jeopardy, but the lives of many Muslim Minnesotans.”

FLORENCE, AZ - FEBRUARY 28: Immigration detainees stand behind bars at the Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), detention facility on February 28, 2013 in Florence, Arizona. With the possibility of federal budget sequestration, ICE released 303 immigration detainees in the last week from detention centers through outArizona. More than 2,000 immigration detainees remain in ICE custody in the state. Most detainees typically remain in custody for several weeks before they are deported to their home country, while others remain for longer periods while their immigration cases work through the courts. (Photo by John Moore/Getty Images)

Immigration detainees stand behind bars at the ICE detention facility on Feb. 28, 2013, in Florence, Ariz.Photo: John Moore/Getty Images

Immigration detainees stand behind bars at the ICE detention facility on Feb. 28, 2013, in Florence, Ariz.Photo: John Moore/Getty Images

The Immigration Gulag

Muhumed and the other detainees arrived at the West Texas Detention facility on February 23.

By that time, Muhumed had already experienced detention at the Carver County Jail in Chaska, Minnesota; the Kandiyohi County Jail in Willmar, Minnesota; the Sherburne County Jail in Elk River, Minnesota; the Alexandria Staging Facility, a for-profit detention center ran by the GEO Group in Alexandria, Louisiana; the Pine Prairie ICE Processing Center in Pine Prairie, Louisiana (also run by GEO); the Freeborn County Jail in Albert Lea, Minnesota; the Nobles County Jail in Worthington, Minnesota; the Freeborn County Jail (again); and Alexandria (again).

The signs that West Texas would be the worst of them all were evident on the bus ride in, Muhumed said. He described the guards who were watching over them as being in their late 20s and early 30s. “Buff guys that work out,” he said, “muscular looking,” the kind of guys that “want to punch someone around,” the kind of guys that do — and did.

Located in Sierra Blanca, roughly 30 miles from the U.S.-Mexico border, the detention center has space for more than 1,000 bodies. Muhumed and the others arrived on a Thursday. The following day, they had their first meeting with ICE.

“The ICE officer kept being agitated when someone asked him a question, but he came there to answer questions,” Muhumed said. “Some of the inmates were concerned about their legal documents, including myself, because a lot of us applied for asylum.” The reason they were concerned, Muhumed explained, stemmed from a fear that U.S. officials would recklessly turn over sensitive case files to dangerous actors in untrustworthy foreign governments. “You are facing a high risk of being tortured because the government will get ahold of it,” Muhumed said.

Rather than listening to those concerns, Muhumed claimed, the ICE official spent most of his time texting while the men asked questions. “He was saying respect me, and then at the time when we were speaking, he was texting, and so some of the guys got mad and then he left. He didn’t come back for a couple of days,” he said.

It was not long after that, Muhumed explained, that a fight broke out between two detainees. The response on the part of ICE’s contractors, Muhumed said, was an indiscriminate pepper-spraying of everyone in the vicinity, himself included. From there, the situation deteriorated rapidly.

For reasons that remain unclear, because ICE won’t say why, Muhumed and a number of the other men seemed to be treated as “high custody” detainees, the most restrictive category applied to individuals in ICE custody. In theory and in law, individuals in immigration detention are not being punished. It is supposed to be detention, and there is supposed to be some sort of difference between the two. This is, of course, largely a fiction, especially in the case of high custody detainees.

According to ICE’s detention rulebook, high custody detainees “are considered high-risk”; “require medium- to maximum-security housing,”; “are always monitored and escorted”; and “may not be co-mingled with low custody detainees.” The book indicates that a single fight between two men would not be sufficient to broadly apply the harshest detention standards available to all, or most, of a group made up of nearly 80 individuals. “The system identifies and isolates the detainees whose histories indicate the characteristics of the ‘hardened criminal’ and who are most likely to intimidate, threaten or prey on the vulnerable,” it notes.

For Muhumed and the others, the apparent threat they posed in the eyes of detention center officials translated to being housed in moldy cells, cut off from other detainees, where the heavy smell of pepper spray lingered. “We didn’t go outside until maybe, like, five days into our stay,” Muhumed said. “I started noticing everyone else was getting sick.”

Muhumed had already experienced his own brush with dangerous medical circumstance while in ICE custody. Back in February, he and number of other detainees he was with at the time, were told they had been exposed to tuberculosis. Through the endless shuffling from one detention center to another, Muhumed never received the medical care ICE and its contractors continued to promise. The abysmal medical care continued in West Texas, Muhumed said. “My throat was closed. I couldn’t speak properly. I was catching a cold, bad.” Muhumed put in for medical care but didn’t get a response until the men were preparing to leave the facility.

Three days into their detention, Muhumed said an official with ICE appeared again. He spoke to the men and, as he was leaving, tapped an official working at the facility on the shoulder. “Let’s go,” Muhumed recalls the ICE official saying. “On his way out, he cursed and said ‘F’d up,’” Muhumed recalled. “That created a problem, that created an anger from the detainees.”

The ICE official left, Muhumed said, and the men were left in an area enclosed by fencing, behind a locked gate. It was then, he said, that a squad of guards in riot gear moved in on them. “Helmets, everything, fully ready for war,” Muhumed said. Muhumed claims the squad included men with shotguns. “I can’t tell the difference in guns but I know it was a shotgun,” he said. “A long one. There were two of them that had it. And a couple of them had Maces and paintball guns.” Muhumed explained, “The entrance is like a square fence that comes in, there’s a little walkway. Then they have a little lock. They lock it from the outside. And they were inside that little bubble. In no way were they or their lives in danger.”

Some of the detainees were angry, Muhumed said, and he was trying to calm them down when the guards let loose a wave of pepper spray aimed at the penned-in men. “One of the guys fell to the ground and had a seizure,” he recalled.

“Please, this guy is dying!” Muhumed recalled pleading. “Can you help him?”

“Back up!” came the response. “All back!”

Muhumed says he and another man picked up the convulsing detainee and pulled him towards the gate. When they reached the front of the enclosure, one of the officers “cocked his shotgun and pointed it at me,” Muhumed said, adding that he will never forget the sound. “I have nightmares about it,” he said.

“No way was that guy under any threat from me or from anyone else, because one, the door was locked, and two, I was helping bring a detainee who was sick out of a seizure. I was bringing him to the front,” Muhumed went on to say. “There is no way that I, or anyone, if we got out of line, could attack them. They were safe.”

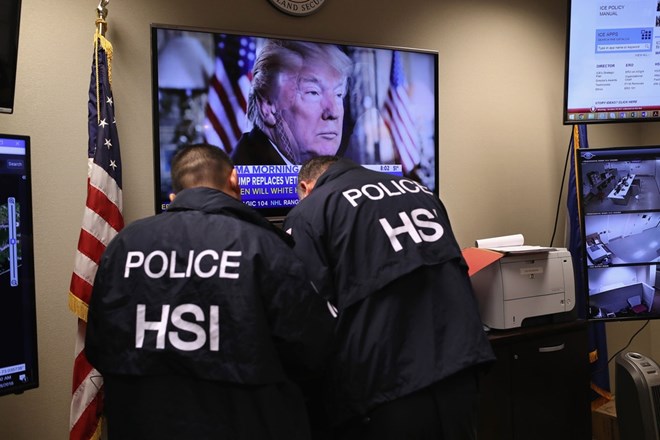

CENTRAL ISLIP, NY - MARCH 29: Homeland Security Investigations (HSI) ICE agents work in a control center as field agents arrest suspected immigrant gang members in Central Islip, New York. Overnight and into the morning, U.S. federal agents and local police detained suspected gang members across Long Island in a surge of arrests. The actions were part of Operation Matador, a nearly year-long anti-gang effort targeting transnational gangs, with an emphasis on MS-13. (Photo by John Moore/Getty Images)

Homeland Security Investigations ICE agents work in a control center as field agents arrest suspected immigrant gang members in Central Islip, N.Y. Photo: John Moore/Getty Images

Homeland Security Investigations ICE agents work in a control center as field agents arrest suspected immigrant gang members in Central Islip, N.Y. Photo: John Moore/Getty Images

“It’s Like Torture in America”

While they were locked up, some of the men managed to contact family members and lawyers and described the conditions they were facing inside the facility. When they were released on March 2 and transferred to the Coastal Bend Detention Center in Robstown, Texas, 30 of the men, all of them Somalis, including Muhumed, sat for interviews with legal advocates from the Immigrant Rights Clinic at Texas A&M University School of Law, the Immigration Clinic at University of Texas School of Law, and RAICES, a Texas-based legal organization.

Their testimonials were compiled in a 23-page report that painted a profoundly disturbing picture of ICE contractors drunk on power. All of the men reported having been pepper-sprayed during their week in detention, and nearly half described physical abuse. One of the men claimed the warden of the facility punched him in the face repeatedly while he was in the nurse’s office. Another said guards repeatedly fondled his penis while he was pushed up against a wall.

Several men recalled seeing detainees thrown to the floor and, in one case, a witness described seeing a guard slamming a man’s head against the concrete “even though he did not resist.” The Somalis said men were tossed into solitary confinement for asking for socks and underwear, for talking too loudly to the warden, and for asking to be sent back to Somalia. Racism was rampant, the men claimed, with officers calling the men “boy,” “nigger,” and “terrorist.” Muhumed told me he personally heard a guard call one detainee a “monkey.”

For Jama, Muhumed’s wife, the entire experience — from her husband’s arrest, to the abuse in Texas, to the looming possibility of deportation to Somalia — has been utterly disorienting. “I feel like it’s like an ongoing nightmare,” she told me.

“Leading up to it, it’s not like we were completely oblivious to things,” she explained. “We know what was going on. We knew Trump was the president.” Still, at the same time, Muhumed was confident that the U.S. government would not come after a guy like him, somebody who had done everything asked of him for the last decade. “We’ve been trying to work on his status but then he kept saying, ‘I don’t think they would prioritize someone like me,” Jama said.

“I don’t understand how you could let someone stay for this long, and not have them be any threat to society — in fact be an asset — and then you just want to destroy his entire life,” she said.

The travel days are the worst, she explained. “When they’re transporting people, they don’t tell you where they’re transporting them to,” she said. “So you’re constantly worried. You have to call multiple agencies. The system doesn’t get updated right away, so you go days without talking to them and not knowing if they got deported or if they’re being just transported because of logistics.”

The men are often told that they can’t sleep during the transportation, Jama explained. So they sit, shackled in a bus, and wait. Just this week, Jama said, her husband sat in a bus, in chains, from 11 p.m. to 4 p.m. the next day. Immigration detention is not supposed to be a prolonged, never-ending experience, Jama noted. “It’s supposed to be because they have your traveling documents, they have everything ready, so now they have you detained, so maybe in a matter of a few days you leave,” she said. “That’s not what happens with Somalis, or Africans.”

As much as ICE and the Trump administration appear intent on deporting people back to Somalia, the actual process is easier said than done. In December, an ICE-charted flight to Somalia returned to the U.S. with its 92 passengers still on board. As The Intercept reported in early March, the men who returned described being shackled on board the aircraft for 40 hours, forced to pee in bottles and on themselves, and said they were beaten by ICE employees. ICE denied the allegations. The logistical challenge of deporting people to Somalia, and countries like it, has meant men like Muhumed are effectively subjected to indefinite detention.

“It’s like torture in America,” Jama said.

TOPSHOT - A man and woman look at the damages on the site of the explosion of a truck bomb in the centre of Mogadishu, on October 14, 2017.A truck bomb exploded outside a hotel at a busy junction in Somalia's capital Mogadishu on October 14, 2017 causing widespread devastation that left at least 20 dead, with the toll likely to rise. / AFP PHOTO / Mohamed ABDIWAHAB (Photo credit should read MOHAMED ABDIWAHAB/AFP/Getty Images)

A man and woman look at the damages on the site of the explosion of a truck bomb in the centre of Somalia’s capital, Mogadishu, on Oct. 14, 2017.Photo: Mohamed Abdiwahab/AFP/Getty Images

A man and woman look at the damages on the site of the explosion of a truck bomb in the centre of Somalia’s capital, Mogadishu, on Oct. 14, 2017.Photo: Mohamed Abdiwahab/AFP/Getty Images

Deported to a War Zone

Muhumed said he had no idea what he would do once he was on the ground in Somalia. “I have no one there that I can contact, that I can call,” he said. His entire family fled the country, and most are in the U.S. “I have no number. I don’t even know who would be picking me up if I did get deported.”

Last October, a month after Muhumed was arrested, terrorists detonated a truck bomb outside a hotel in the capital city of Mogadishu. Nearly 600 people were killed and hundreds of others were wounded, making it among the deadliest bombings in the nation’s history. “I’m afraid to go to a hotel,” Muhumed said.

Muhumed is certain he would be a marked man in Somalia, both because he’s from the U.S. and because of his public denunciations of the terrorist groups operating in the country. Growing up, he told me, he never learned what tribe his family belongs to. “I can’t tell the difference between this tribe and that tribe,” he said, and in Somalia, not being able to tell the difference between tribes can have serious consequences.

What gnaws at Muhumed most is the fact that all of this stems from mistakes he made when he was young. “I’m in this situation for something I did years ago, a decade,” he told me. “Whatever you did in the past haunts you.”

Thursday, March 29, marked six months since Muhumed was arrested. By law, ICE cannot detain a person who has final order of removal for longer than six months if it’s unlikely they will be removed in the reasonably foreseeable future. Muhumed and his family had planned to file a claim to make that argument, but early Thursday morning, at approximately 3 a.m., he and his fellow detainees were loaded onto a plane — bound for Somalia.