Sunday March 18, 2018

By Joanne Hayden

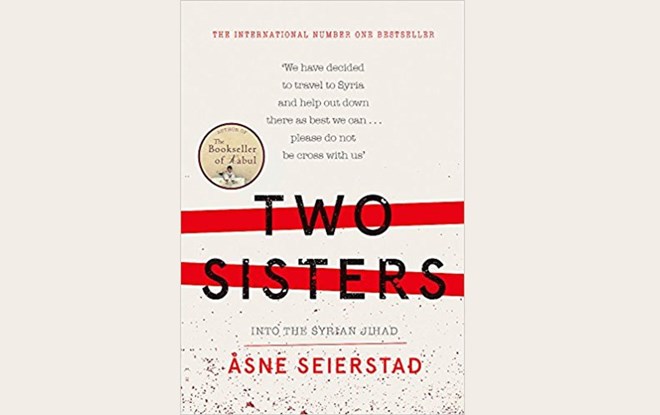

Non-fiction: Two Sisters: Into the Syrian Jihad, Åsne Seierstad, Virago, hardback, 399 pages, €14.40

In Two Sisters, Norwegian journalist Åsne Seierstad uses her considerable investigative prowess to trace how Ayan and Leila - resourceful young women with seemingly bright futures - came to embrace the ideology of Isis. She paints a comprehensive portrait of their parents - their mother Sara, who never fully adjusted to life in Norway, and their father Sadiq, more liberal than many of his peers, encouraging his daughters to play sport and deeply unhappy when they first began to wear the niqab or face veil.

It's a complicated, expansive story with multiple locations and a large cast of characters. Seierstad does an excellent job of weaving the different strands of her narrative together, moving backwards and forwards in time and jumping between Oslo, Somalia and Syria so cohesively and so strategically that the book often reads like a thriller.

Determined to get his daughters back, Sadiq travels to the Turkish-Syrian border and, with the help of a middleman, makes it into Syria. The sisters are tracked down and he is allowed five minutes with Ayan, who is already married to an Isis fighter. Sadiq asks her to come home; she refuses. He is imprisoned, interrogated and tortured, cellmate after cellmate is taken away, but he gets out.

Like in The Bookseller of Kabul - Seierstad's hugely successful account of daily life in an Afghan household following the fall of the Taliban - Two Sisters adopts a novelistic form. The writer does not appear on the page. Instead she tells the story in a third person voice, entering into the minds of her subjects as though they are fictional characters.

The form has plenty of literary forebears - not least Truman Capote's seminal In Cold Blood - and is partly what makes the book so compelling. Nevertheless, it's a distinctive and unsettling choice, as Seierstad knows.

Published in English in 2003, The Bookseller of Kabul generated almost as much controversy as fame for its author when the book's central figure objected to how he and his family were portrayed; his second wife sued Seierstad for defamation. In a chapter at the end of Two Sisters, Seierstad emphasises that Sara and Sadiq reviewed the finished manuscript. She details her research methods and her copious sources. She also asks a question that will be in many of her readers' minds.

"Is it ethically defensible to focus on the lives of two girls when they have not granted their consent?"

Her answer is yes. "The entire world is trying to understand the reasons for radicalisation among Muslim youth," she says. She believes that as a journalist, it's her task to put her finger "on problematic aspects of society".

This same sense of purpose informed One of Us, her 2013 book about Anders Breivik's 2011 terrorist attacks in which 77 Norwegians were murdered, and in many ways - in its investigation of the relationship between public and private spheres for example, in how it contextualises the war in Syria as adeptly as it captures the realities of the Juma's domestic lives - the book realises the breadth of its ambition. But although Seierstad opens a window on to different worlds, the fact that Ayan and Leila are simultaneously present in, and absent from, the narrative is problematic.

The story can't really end. By necessity, several questions are left unanswered. Do the sisters still endorse Isis? What will happen to them and their young children? Seierstad goes as far as she can to get at the truth but despite her exhaustive efforts to understand the sisters' departure, it's still not fully clear why they went.

Indo Review