Friday January 12, 2018

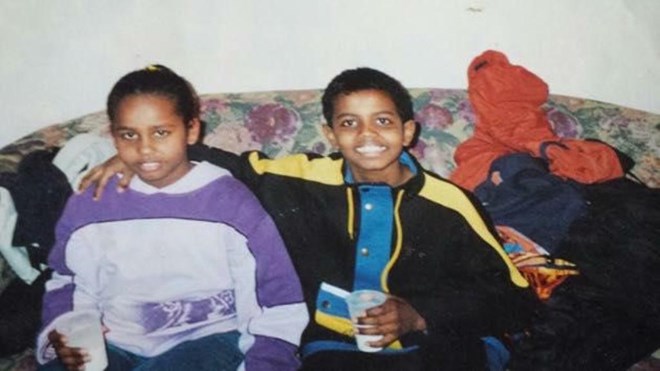

Abdoulkader Abdi, who grew up in government care, could be deported because Nova Scotia officials never applied for his citizenship

After finishing a prison sentence for crimes he committed as a young adult, Abdoulkader Abdi hoped to be released last week to a halfway house in Toronto and on his way to being home with family. Instead, he was re-arrested by Canadian border officials and thrown into immigration detention.

Now the 23-year-old former child refugee from Somalia, who is a product of Nova Scotia’s foster care system is facing deportation back to a country he hasn’t seen since he was six and where members of his family were murdered when he was a child, according to his lawyer.

The Canadian government often tries to deport refugees back to their home countries after they’ve been found inadmissible because they’ve committed serious crimes. What makes Abdi’s story unique, though, is that he’s been in government custody since he was seven years old, and his citizenship application fell through the crack at the hands of government workers.

Unlike Canadian citizens who are free after they’ve served a sentence, Abdi is facing what immigration experts call “double punishment” — also being deported from home — because the government actively prevented his family from including him on their own citizenship application and also failed to apply on his behalf.

The case has drawn strong criticism from refugee advocates and youth protection workers across the country. Justin Trudeau was asked about Abdi at several recent town halls and Nova Scotia’s premier is promising to review not only Abdi’s case, but also other similar cases in the province.

FROM FOSTER CARE TO PRISON

With no translator to explain the situation, his aunt Asha Abdi had no choice but to surrender the children that day, she told VICE News. She and Fatuma now believe the siblings were apprehended because their aunt took too long to register them for school after the family moved from Sydney to Halifax, although the rules were never properly communicated, they said.

“All that time, we were communicating by dictionary and translator over the phone,” Asha told VICE News.

While the Nova Scotia Department of Community Services wouldn’t speak to the specifics of the case, they said they “adhere to a standard of practice that includes taking whatever immigration steps are needed, particularly as children in care transition into adulthood.”

The standard is now being developed into a formal policy, the department said in a statement to VICE News.

POLITICAL FALLOUT

Speaking with reporters on Wednesday, Nova Scotia Premier Stephen McNeil said there would be a complete review of Abdi’s case, along with “any cases that would require the kind of support that I’m hearing about with this particular gentleman.”

“I’ve asked... what are the options that we are providing and laying out to all children in care,” he said. “Then it is up to those children as they grow into [their] teenage years to decide whether or not they take advantage of those options.”

“The province can’t force you to take out citizenship,” McNeil added. “The province can provide you the support and provide you the options to gain citizenship, but it is up to the individual to determine whether or not they want citizenship.”

In a town hall on Tuesday in Sackville, N.S., Fatuma demanded an answer from Prime Minister Justin Trudeau.

“Why are you deporting my brother?” she asked. “If it was your son, would you do anything to stop this?”

Trudeau called Abdi’s story “an important one,” and admitted that the care system had “failed” him. While he didn’t speak directly to the details of the case, he assured Fatuma that Canada’s immigration minister Ahmed Hussen, who also came to Canada as a Somali refugee, “understands the challenges and the situation [her] family is facing right now.”

“Any time the government has to issue a deportation order… it’s something we take very seriously,” he said, adding that no final decisions had been made.

Canada will “do what Canada always does and try to do the right thing based on both rules and compassion not just for your brother but for everyone who comes to this country,” Trudeau said.

'TERRIBLE IRONY'

After he and his sister were placed in foster care, Abdi was “terrified,” he wrote in an affidavit. “I did not speak English. Shortly thereafter, we were transferred to the children’s hospital in Halifax, where we were held for examination for what seemed like an eternity.”

While his aunt tried repeatedly, without success, to regain custody of the children, Abdi was bounced around between a total of 31 different group and foster homes. He was never adopted and only finished school up to grade 6.

"The terrible irony in this case, or one them at least, is that children that are apprehended because they’re deemed in need of protection are done so on the assumption that they’re going to be better off in state care than with their family,” said Benjamin Perryman, the lawyer representing Abdi in the federal court case that presents charter and international law arguments on his status. Abdi now faces the greatest danger he’s faced in his life, Perryman added — being deported to Somalia

Canada currently doesn’t deport people to Somalia, which it considers to be a country in the midst of a “humanitarian crisis,” unless they’ve been found inadmissible to Canada because they've been convicted of a crime. But even in those cases, the government has been struggling to send people back because Canadian officials can’t accompany them and most airlines won’t travel to the country.

“I don’t even know my culture no more,” Fatuma said, adding that because they didn’t grow up with their Somali family, her brother also has no relationship with Somalia. “They stripped me from my culture. They put me in group homes where I wasn’t allowed to speak my language. I can’t speak two sentences to you in my language.”

CONFLICT WITH THE LAW

Abdi was born in Saudi Arabia to a Saudi father and a Somali mother. After his parents got divorced, the family left Saudi Arabia for Djibouti as refugees because of the ongoing civil war in Somalia. Abdi’s mother died in the refugee camp, and his aunts Asha and Hawa went on to raise him.

All of Abdi’s family is in Canada—his daughter, sister, nephews, and aunts — and Abdi considers himself Canadian. Fatuma didn’t even realize she wasn’t a citizen until her brother got in trouble with the law.

When he was nine or 10, Abdi and his sister were placed with a foster family who he describes in his affidavit as a “physically and emotionally abusive” because they yelled and beat him for not being able to read. While his sister was eventually taken out after making allegations of sexual assault and attempting multiple times to run away, Abdi was afraid to complain, believing no one else would take him in. He also tried running away repeatedly. Once, when he took the family’s car and drove around Halifax trying to find his sister, the police found him and brought him back home. “It was at this point that I started having conflict with the law,” he wrote.

FEARS FOR CHILD

Fatuma blames Nova Scotia’s youth protection system for her brother’s troubles, saying he was left for years in an abusive situation and provided with no therapy or parental guidance throughout his childhood, but “thrown into the jungle.”

Throughout his time in care, Abdi never realized he wasn’t a Canadian citizen. When he was 14, he was told that staff were trying to get him a passport and that they retained a lawyer to help with the case. He was also granted a social insurance number. But somehow, the citizenship application never materialized.

In 2014, Abdi pleaded guilty to aggravated assault and assault of a peace officer with a weapon, as well as theft and dangerous operation of a motor vehicle. He’s also been convicted of a number of offences committed during his time in jail and has a prior record of other adult crimes, ranging from failing to comply with conditions to carrying a concealed weapon.

“As a teenager, I did not understand the negative implications that being a non-citizen would pose for me down the road,” wrote Abdi. “While I am ultimately responsible for my criminal convictions and am serving my time for the choices I have made, I am not responsible for the fact that I am a non-citizen.”

Abdi, who is a young father to a three-year-old girl named Farrah, recently learned that the Department of Community Services has taken steps to apprehend his daughter from her mother. His sister Fatuma says she also had a child who was apprehended and subsequently died in care. The baby, which was born premature and was recovering from jaundice, was taken after police raided her home in search of the weapon Abdi allegedly used in an assault, she said.

“I would do anything for Farrah not to go through the experience I had of growing up in care,” Abdi wrote in his affidavit about his daughter. “I want to be there for her and support her once I am released from jail. If I had to work three jobs to help her have a different life than me, I would do that.”

'FACING DEATH'

The Canadian Council For Refugees (CCR) has recommended to the government that criminal inadmissibility not apply to people who are permanent residents or protected persons who have been in Canada for three of the last five years.

The organization is also concerned about youth protection agencies that fail to pay proper attention to non-citizen children under their care and their status.

Janet Dench, executive director of CCR, said one factor is that youth protection is a provincial responsibility, while immigration is federal.

“But in too many cases, there’s a complete breakdown in terms of understanding of the situation, where the children in care obviously and rightly assume the adults are looking after their best interests,” said Dench, adding that it’s “unfortunately well established that children who have been through youth protection disproportionately end up in the criminal justice system.”

He's currently incarcerated in Toronto, Adbi's lawyer said on Thursday. Abdi’s next detention review is on January 15, while the date for his next deportation hearing has not yet been set.

“I really just want people to see we were just kids coming here,” said Fatuma. “The government had every right over us, and because they failed on our behalf, my brother is facing death.”