Tuesday January 2, 2018

Eight years ago, Khadija Abdi fled the fighting and chaos in Somalia that killed her father and brother and made it across the border to a refugee camp in southern Ethiopia.

Life isn’t so bad here, she says. Tents have gradually been replaced by huts. She is safe, and her daughter goes to school.

The problem: There’s not enough food.

“Three times this year, rations have been cut,” Abdi, 40, said of their monthly allotment of grain, pulses, cooking oil and salt.

Beset by funding shortages, the U.N. World Food Program has reduced the daily calorie intake for the 650,000 refugees it feeds in Ethiopian camps by 20 percent, leaving them with an average allowance of just 1,680 calories a day. According to the U.S. Department of Agriculture, men need on average about 2,500 calories a day, women about 2,000.

If new funds do not come by March, the refugees will see a further drop, to about 1,000 calories a day. Meanwhile, nearly 10,000 new refugees, mostly from war-torn South Sudan, arrive every day.

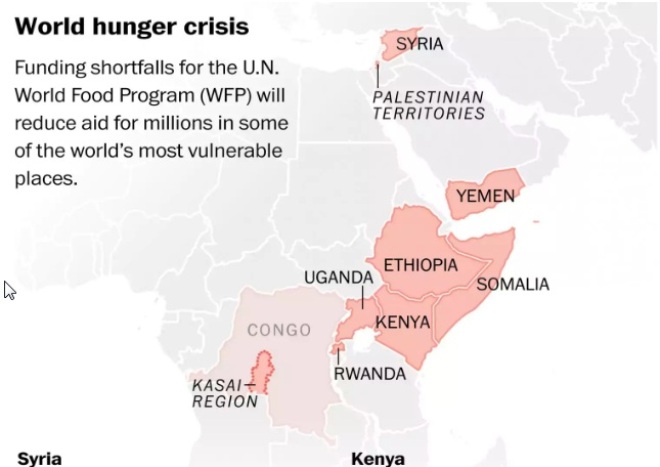

“It’s the huge demands that have outstripped donors’ ability to keep increasing funding,” Smerdon said. With near-famines in South Sudan, Yemen, Nigeria and Somalia, as well as a string of protracted conflicts and refugee crises in places such as Syria and Ethiopia, the need is simply too great.

In 2016, the WFP needed $8.84 billion and received $5.92 billion, including the United States’ $2 billion. A year later, the need rose to $9.6 billion, but funding was just $5.96 billion — a slight uptick but a bigger shortfall. There is no reason to expect 2018 needs to shrink as conflicts continue unabated.

“The donors are giving more, but I am concerned and worried that this cannot continue,” Smerdon said. “It’s only development that’s going to fix the problem. We are just the Band-Aid.”

A Band-Aid, however, that is everywhere. The WFP funding cuts will affect a staggering number of people.

In Syria, where a six-year-old civil war is slowly winding down amid massive devastation and displacement, the WFP has been able to feed fewer people every month, dropping from 4 million in November, to 3.3 million in December and an expected 2.8 million next month.

In Yemen, where a civil war and a foreign blockade make it hard just getting food into the country, half of the 7 million people fed by the WFP are on 60 percent rations (1,260 calories a day). Similarly in Somalia, where 3 million people receive assistance, the WFP has had to suspend rations for many and reduce them for others.

In Kenya’s sprawling Dadaab refugee camp, the ration cuts have put many of the more than 200,000 Somali residents into debt and forced them to go back to precarious lives in conflict-ridden Somalia in return for money to pay off their loans.

so far in Ethiopia, in contrast, there has been no pressure from the government to repatriate Somalis, and what little most refugees hear about what’s going on there — including a truck bomb in Mogadishu in October that killed more than 500 people — keeps them from wanting to return.

“I think about my father and my brother, and I don’t want to go back,” Abdi said. “When I heard the story of the bomb in Mogadishu, my mind went back to what happened eight years ago.” Before she made it to Ethiopia, Abdi and her family fled from city to city to escape the fighting that eventually claimed her father and brother.

Lately, the camps in this area have been receiving U.S.-donated white sorghum, a grain used for food and animal fodder in many parts of Africa — but not in Somalia. The Somali refugees abhor the taste, and worse, can’t sell it to the local community. Most camp residents try to sell some of their monthly allotment of grain to buy things aid agencies don’t provide, such as milk, sugar and clothing.

“The white one makes the animals sick when they eat it, never mind the humans,” said Mohammed Isak Hassan, who fled Somalia’s al-Shabab militant group nine years ago and now teaches children with developmental disabilities in the Bokolmanyo camp, not far from Melkadida.

He also lamented that the ration of enriched CSB+ flour, popular with his five children, had been cut from three pounds a month to one.

He eyed with suspicion the dried kidney beans now being distributed in place of the more familiar lentils.

“It’s not just food for them, it’s income to meet the needs for what we don’t provide,” said George Woode, head of the U.N. refugee agency’s local office, about the ration. “It’s a bartering system.”

As the cycle of conflict and refugee flows continues around the world, there is a glimmer of hope at least for those in Ethiopia, where in 2016 the government pledged to boost ties between the refugees and the host communities and help them initiate their own income-generating activities, including partnership ventures.

The government has also promised to reserve some jobs for refugees in new industrial parks.

These southern Ethiopian camps are among the best suited for this experiment in making refugees more self-sustaining because the members of the host community, Ethiopians of Somali origin, speak the same language as the refugees and in many cases are from the same clans.

“What we are looking at more and more is a shift from basic services and basic assistance to self-reliance,” Woode said as he detailed plans for micro-credit schemes and vocational training.One of the most ambitious projects involves taking 24,700 acres of land donated by the Ethiopian government and irrigating it, letting both refugees and locals farm it.

The project, already underway, could ultimately sustain much of the drought-stricken area’s population.

For now, there are many mouths to feed.

“When you have the same pot of money to support a growing number it just means everyone is going to get less,” said Leighla Bowers, the WFP’s Ethiopia spokeswoman. “The fact of the matter is refugees just keep coming in.”