Tuesday December 11, 2018

Foreign navies have played a key role in curbing piracy off Somalia's coast, writes the BBC's Anne Soy.

On a beach in Hordeia on the northern coast of Somalia, I asked a former pirate what attracted him to piracy in the first place.

The man, who wanted to remain anonymous, told me he was originally a fisherman and that was his main source of income but things changed when an illegal trawler destroyed his net.

"I had a boat and a net on it, then a trawler cut our fishing nets and pulled them away. I was left with an empty boat," he recalled.

He and a fellow fisherman tried to shout and call the trawler crew, but it was in vain. It angered them.

"They passed over our nets and pulled them away. Our fishing equipment was destroyed."

Fishermen are being encouraged to resume their trade

The former pirate's story was not unusual.

In the second half of the last decade what began as a defensive act against big trawlers, quickly morphed into a lucrative illegal business that raised global concern.

As he and other fishermen lost their trade, they turned to piracy, hijacking ships and passengers for ransom.

Dramatic cliff

It also drew in former militiamen who fought with warlords during Somalia's long civil war.

I wanted to know more about his days as a pirate but he became unsettled and ended the interview abruptly.

What appeared to make him uneasy was a Spanish Special Forces soldier who had wandered over.

Security around the beach was tight as a helicopter hovered in the sky. The helicopter was part of the European Union Naval Force (EUNavfor).

The presence of foreign warships has made the coast safer

It gave a clue as to what has changed in recent years that has dramatically reduced the threat from piracy.

A decade ago, pirates operated freely and there were plenty of hideouts for them along the coastline, like Eyl, a small, scenic port town in Somalia's semi-autonomous region of Puntland.

As I approached Eyl, I saw the town by the beach right in front of a high, dramatic golden-brown cliff. The cliff seemingly shelters the town from wind and dust blowing from the mainland.

Dangerous sea passage

Locals told me about the time years ago when pirates flooded the market with money, causing the cost of living to rise sharply.

Armed, they also terrorised the local community, but they rarely killed anyone.

They also held some of the sailors they captured hostage as they demanded huge ransoms, sometimes of hundreds of thousands of dollars.

The possibility of huge riches seemed to have been the main driver of piracy off the Somali coast.

But it was the lack of an effective central government since the collapse of the Siad Barre regime in 1991, and the subsequent disbandment of the Somali navy, that enabled it to happen.

Somali territorial waters saw a rise in smuggling, illegal fishing by foreign trawlers, illegal dumping and later piracy.

The route through the Indian Ocean past the Somali coast became known as one of the most dangerous sea passages in the world.

But 10 years ago, the European Union, Nato and others began to deploy naval forces to the region shortly after the UN Security Council allowed warships to enter Somali territorial waters.

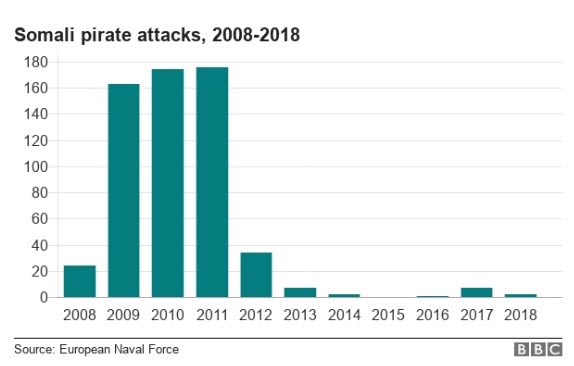

Pirate attacks have now all but stopped, after reaching a peak in 2011.

I wanted to see how this change had come about and spent seven days on the ESPS Castilla, a Spanish naval ship that is part of EUNavfor.

On the second day onboard, breakfast was cut short and we were guided to the ship's bridge. A boat had been spotted in the distance.

"We don't think it's anything suspicious but we carry out 'friendly approaches' as part of patrolling the sea," explained an officer.

After a quick briefing, five or so marines geared up and descended from the warship onto a waiting boat. We followed on a second boat, keeping our distance.

Rich fish stocks

As soon as the Spanish boat had pulled alongside the fishermen, a quick search was conducted.

"The vessel is from Yemen but the crew are mostly from Somalia," the officer on our boat explained after listening to the radio communication.

Finally, we were allowed to board the fishing boat.

The fishermen, about eight of them, were by then relaxed and making jokes as they drank water from bottles given to them by the special forces.

"There's a good market for fish in Yemen that's why we sell our catch there," explained Osman Ali.

Fishermen say security has improved since the deployment of the EU force

He said he used to fish off the coast of Tanzania, but was attracted further north because of the rich fish stocks in Somali waters.

"But I have not seen pirates," he said nervously and quickly changed the subject.

All the fishermen operating here know each other and if there is a security problem they quickly alert their colleagues and move to safer waters, he added.

"Sometimes we meet bad people who steal our tools and fish, but the presence of the warship has made things better," Mr Ali said.

Boat blown up

On another day, news came through that a freight ship came under attack 300 nautical miles east of Somalia's capital, Mogadishu.

A small boat, or skiff, got within 50m (164ft) of the ship and fired. But the onboard security returned fire, scaring off the small boat.

Back to fishing

Eyl Police Commissioner Mohammed Dahir Yusuf exuded confidence about the town's ability to deal with any resurgence.

"Any illegal boats are dealt with by the marine forces who catch them and bring them here, where they are dealt with."

He was referring to the Puntland Maritime Police Force, around 800 men strong, and the largest such unit in the country.

But its abilities are limited.

"We don't have enough boats to take to sea," Mr Yusuf said.

Puntland's maritime police force is small

He added that the force only had two small boats, hardly enough to adequately patrol the vast sea and apprehend suspects.

This is not the only challenge.

Marco Hekkens, an adviser on maritime security to the EU's civilian mission in Somalia, said illegal fishing is continuing.

EUNavfor can report suspicious fishing vessels to the authorities, but given Somalia's limited capacity to deal with them, hardly anything is done.

Rear Admiral Alfonso Perez de Nanclares is also cautious despite the success in quelling piracy.

"When the mission started we had about 40 hijacked ships, and more than 700 hostages," he told me.

"Piracy has been contained but I really think the intention of going back to this business is still there. I think by working together [with the authorities] we'll be able to suppress and eradicate it."

Back in Hordeia, before the reformed pirate got cold feet, he told me that he had gone back to fishing.

But there continues to be a danger that the piracy cycle could be repeated.