Friday June 23, 2017

By Ibrahim Hirsi

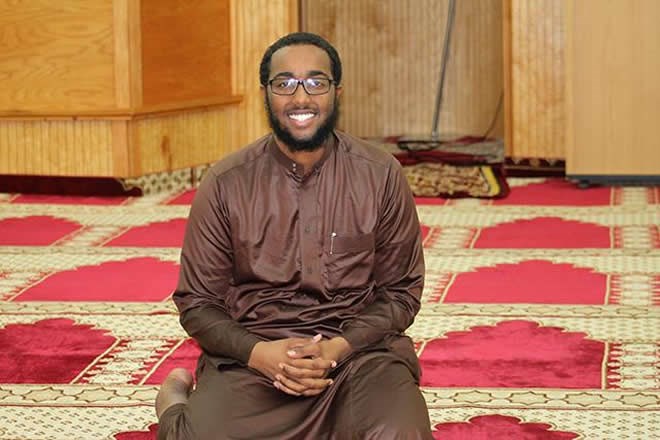

Mohamed Jama Hassan, 19, shown at Masjid al-Rawdah in south Minneapolis. MINNPOST photo by Ibrahim Hirsi

Most days, when 19-year-old Mohamed Jama Hassan concludes his summer internship at Augsburg College, he does something most people his age don’t do: He goes straight to the mosque.

That routine is even more important during Ramadan, the month in which observant Muslims fast from dawn to dusk. Around this time of the year, one Minneapolis mosque, Masjid al-Rawdah, becomes more like his second home.

On a recent afternoon, when Hassan woke up from a nap at the back of the mosque, a man signaled him from the other corner of the mosque to make the adhan, a call to prayer.

It was 5:10 p.m., and Hassan — wearing the long-sleeved garment known as a thobe — rose from the carpeted floor and poured his voice into the microphone, announcing the day’s third prayer, Asr. “God is most great,” he recited in Arabic. “Come to prayer. Come to success.”

Ten minutes later, the empty mosque became half-full. But one thing stood out among the faithful: Nearly all of them were gray-haired men aged between 40 and 70 — a reality that’s also common at most Somali-run mosques in Minnesota.

“Young Somali-Americans don’t feel welcomed at mosques,” said Hassan. “The imams can’t relate to them because they don’t speak the same language; they don’t know how to connect with young people. There is a big cultural divide, unfortunately.”

The growth of Somali-run mosques

Before the Somali community began their journey to Minnesota almost three decades ago, there were only a small handful of mosques in the state.

Then, in 1998, the first Somali-run mosque, Dar al-Hijrah Islamic Civic Center, was built in Minneapolis’ Cedar Riverside neighborhood, an area that now has the largest concentration of Somali-Americans in the U.S.

At the time, only a couple of thousand Somalis lived in Minnesota. So each Friday, most of the congregation streamed into Dar al-Hijrah for the day’s special prayers and lecture. To accommodate the worshippers, the center organized multiple services, where the crowd sometimes spilled into the parking area, said Sharif Abdirahman Mohamed, the imam of the mosque.

As the population of Somali-Americans and other Muslim communities in Minnesota grew, however, so did the number of Islamic centers in the state. Since 1998, says Mohamed, the number of mosques in Minnesota increased four to nearly 50 today.

And while a few are operated by the African-American, Middle East and Oromo communities, Somalis have established the vast majority of those mosques. Most are concentrated in the Twin Cities metro area, though a growing number of the Somali-American community in St. Cloud, Rochester, Faribault and other Greater Minnesota cities has opened several mosques and religious schools.

A cultural divide

Hassan, who was born and grew up in Minneapolis, has been an active member and a volunteer at several different Minneapolis mosques. Throughout those years, Hassan noticed one recurring trend in the Somali-run mosques: Young people generally don’t feel welcome.

There are several reasons why they feel isolated, but the main one has to do with a deep cultural divide between the community’s older generation and younger Somali-Americans, especially millennials. For the most part, religious leaders and older mosque-goers often expect younger people to speak Somali, Hassan says, dress “properly” and cut their hair as if they have an important job interview.

Many younger Somali-Americans, however, live in a different world. Some are big fans of the NBA players and pay attention to hip-hop culture, from which they take their fashion cues. That often means that the young men may come to the mosque with hairstyles that often draw negative attention from older worshippers and religious leaders. “They will ridicule you because of your hair, your appearance,” Hassan said. “There’s a lot of judging at mosques. It’s what makes a lot of young people not want to come near.”

But even if young Somali-Americans — most of whom were born or grew up in the U.S. — follow the proper mosque etiquette, the cultural and language barriers still force them out of the congregation, said Masjid Al-Rawdah Director Mohamed Farah.

That’s because imams at most Somali-run mosques in the Twin Cities offer important Friday lectures in Arabic or Somali, languages most young Somalis don’t understand. “The sheiks like to speak in Arabic and Somali,” Farah said. “They don’t know English. But even if they try [speak English], our youth don’t understand them. It’s funny to them to hear the sheiks’ broken English and the way they pronounce the words.”

It’s not only the language or cultural divide that young Somalis can find off-putting, however. Many also find the lectures imams deliver as irrelevant to the day-to-day lives of the Muslims living in America. “They talk about what a Muslim should do when slaughtering an animal,” Hassan said. “That’s good to know, but how many of us really slaughter animals on a regular basis? I mean, we’ve got Whole Foods here.”

A lack of activism

Since 2014, when the Black Lives Matter movement rose to national prominence after the shooting of the 18-year-old black teenager, Michael Brown — young Somali-Americans in Minnesota have become increasingly involved in social justice issues.

Over that time, most of those activists have seen leaders from other faiths — priests and pastors and rabbis — on the frontlines of demonstrations, protesting in solidarity with black victims of police shootings or against the Trump administration’s plan to ban some Muslim refugees from entering the country.

What young Somali-Americans don’t see during such events, Hassan and Farah say, are imams and other mosque representatives. Nor do they often see them participating in political discourse — or taking public stands on policies that affect Muslims and communities of color. “The reason the mosques aren’t involved in the Black Lives Matter isn’t because they don’t want to be part of it,” Farah said. “It’s because they are not aware of what’s going on when it comes to social justice issues or politics.”

Mohamed, the imam of Dar al-Hijrah, agrees with Farah’s sentiment. Most of the mosques and imams want to partake in social justice activities, he said, but are often reluctant because they aren’t familiar with the system. “Social activism isn’t just something you do,” he added. “It’s learned. The churches have been part of social activism for centuries. It’s very new to us. Somalia never had social activism before. … We’re still learning.”

All that said, Mohamed noted, mosques haven’t been completely absent from advocating for certain causes. When Jamar Clark was shot and killed in north Minneapolis in 2015, he said, about 20 mosques wrote a statement in support of the victim, with Dar al-Hijrah being one of them. “But I understand we haven’t done as much as we should have done,” Mohamed said. “About a year ago, I talked to Islamic scholars about that and the need to be more involved in social justice issues.”

Training future faith leaders

Some young Somali-Americans are trying to do their part to fill the divide between Muslim millennials and mosque leaders.

Hassan, a sophomore at Augsburg College, has been a faith leader even when he was a student at Minneapolis’ South High School, where he founded a Muslim Student Association and advocated for a student prayer room in the school.

He’s also part of The Brothers Club, a group of young Somali-American Muslims who produce weekly YouTube talk shows in English. In one video, published in May, aimed at high school students, Hassan and two other men talked about the importance of education.

“Those who are going to school, be grateful that you’re going to school,” he said in the clip. “Be grateful that you’re waking up. Be grateful that you’re in peace, not in war.”

In another The Brothers Club YouTube video, uploaded on Thursday, Hassan discuses “seven common mistakes” to avoid on Eid al-Fitr, the Islamic celebration marking the end of Ramadan — information most Somali mosques would likely give in Somali.

Aside from providing Islamic lessons in English via social media, young Somali-Americans are traveling to the Middle East for Islamic studies. Several have recently returned to Minneapolis, and are often invited to speak at youth conferences cross the state.

Moreover, many Somali-American millennials are also attending the Twin Cities-based Islamic University of Minnesota, which provides religious education of all levels, including associate, bachelor’s, master’s and Ph.D. degrees.

Some mosques are also doing their part to train aspiring young Somali-American faith leaders. Farah, for example, said he’s been encouraging young people to pursue education in Islamic studies to become the future leaders of the growing mosques in Minnesota. Beyond that, Farah provides young Muslim Americans with opportunities to get involved and even give the Friday lectures.

“We need to prepare people like Mohamed Hassan to become the future leaders of the community,” he said. “They understand and can relate to our young generation. I hope that’s a step other mosques will also take.”