Sunday August 20, 2017

By Tristan McConnell

Pressure is mounting against multi-faceted smugglers but the legal case, though strong, is enormously complex

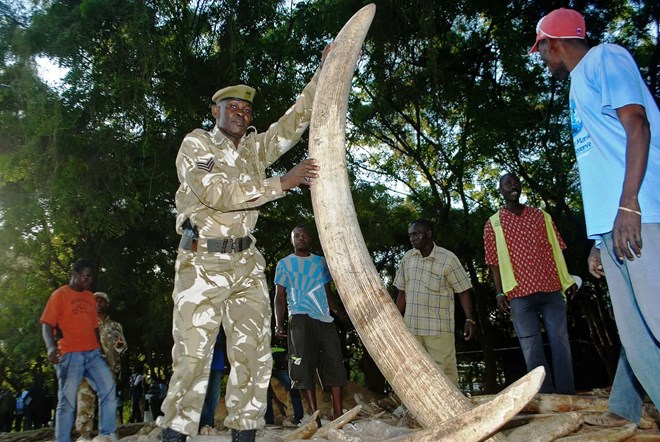

A wildlife service officer holds one of the ivory tusks used as evidence in the case against Feisal Mohamed Ali. Photograph: Stringer/AFP/Getty

Late on 6 June 2014 Kenyan police, acting on a tip-off, raided a used car lot in Mombasa’s industrial area. Inside Fuji Motors East Africa Ltd, in one of the lock-ups, they found two tonnes of ivory.

Days earlier a white Mitsubishi truck, its paperwork claiming “household equipment” but in fact carrying more than 300 elephant tusks secreted beneath a tarpaulin, had pulled into the yard on Mombasa Island’s dirty northern fringe, far from the tourist hotels and beaches for which the city is famous.

The discovery led to one of the biggest, most high-profile trials of an ivory smuggler to date. Five people were arrested, but the key suspect, Feisal Mohamed Ali, disappeared, first to the Kenyan capital Nairobi and then to neighbouring Tanzania. Interpol issued an environmental crime arrest warrant – among the first of its kind – and Ali was eventually found in Dar es Salaam in late December. He was extradited and charged in Kenya on Christmas Eve.

Ali’s trial progressed in fits and starts. Evidence disappeared, judges were replaced, bail applications were denied, consented to, appealed and overruled, pleas for medical treatment were made and then abandoned, death threats were issued to activists observing the trial – but in July 2016 Ali was finally convicted and sentenced to 20 years in jail and a 20 million shilling (£146,000) fine for ivory possession. He is currently appealing. The heavy sentence was exemplary: proof that a recently passed wildlife law worked and that traffickers caught in Kenya would no longer get away with paltry fines for their supposedly trivial crimes.

The conservation organisations, which had kept a close eye on the courts, piled pressure on the government and prevented the case from collapsing through subversion or neglect, cheered Ali’s conviction, as did wildlife advocates and elephant lovers who had watched the case with appalled interest.

But for others – an informal collection of investigators working to expose the wildlife trafficking networks that have been operating with impunity across Africa – this was just a welcome opening to a far far bigger task.

The networks behind the smugglers

“It’s not hundreds of groups involved in ivory trafficking – there are just a handful of networks operating across Africa,” says Paula Kahumbu, a conservationist and elephant expert who runs Wildlife Direct, a Kenyan organisation working to stop the ivory trade and which deploys teams to closely observe trials such as Ali’s.

Close scrutiny of cases – including making copies of court documents and video recording proceedings – keeps courts and judges honest and prevents the disappearance of files that so often scuppers trials. Wildlife Direct’s pressure was instrumental in ensuring Ali’s case went the distance. At the end, says Kahumbu, there was “a phenomenal sense of achievement”.

“It was a huge surprise,” says Ofir Drori, an Israeli wildlife activist and co-founder of the Eagle Network, a group responsible for the prosecution of hundreds of traffickers, big and small, over the years, and who was involved in tracking Ali. “Every Kenyan will tell you: what’s supposed to happen is that if you belong to a strong syndicate, you’re out.”

It was the syndicate aspect that interested Gretchen Peters. A former foreign correspondent in Afghanistan and Pakistan, Peters had become fascinated by the links between drugs and terrorism that she saw in the Taliban’s heroin operation, and by the hidden connections between other forms of criminality. Ditching journalism, she decided to tackle wildlife crime.

Feisal Mohamed Ali has been sentenced to 20 years in jail. Photograph: AFP/Getty Images

Peters set up the Satao Project – named after one of Kenya’s magisterial “tusker” bull elephants, killed by a poacher’s poisoned arrow in 2014 – to investigate criminal gangs in 2015 but quickly ran into the underlying problem: corruption. “If there’s a network that is moving illegal goods from one country to another, there are inevitably government officials involved, protecting them or looking the other way,” she says. “It is impossible for that not to be happening.”

Hired by the US department of state, Peters began by studying ivory supply chains in Tanzania and Kenya, but her investigations quickly enveloped Uganda too and spread into other forms of trafficking. There is in East Africa, she says, “a regional ecosystem moving ivory, drugs and guns … a matrix of different organisations that collaborate to move illegal goods along the Swahili coast.”

The overlap between drugs and ivory smuggling came as no surprise to her. “I’m not aware of any syndicate trafficking ivory transnationally that is only moving ivory,” she says. No illicit commodity is as profitable as drugs, so: “When you get up to the traffickers they’re almost inevitably moving narcotics too.”

Other investigators had come to the same conclusion. Ali is the biggest ivory trafficker to be jailed in East Africa, yet investigators say he answers to others. “Feisal [Ali] is not a kingpin: he is a soldier, an employee,” says Drori.

Peters began connecting Ali and the wider narcotics syndicate for which she was convinced he was working. One of the key pieces of evidence in the trial was Ali’s mobile phone records. “The call logs are what nailed Feisal,” says Jim Karani, the legal affairs manager at Wildlife Direct.

Conservation activists demonstrate during the trial of Feisal Mohamed Ali. Photograph: Tony Karumba/AFP/Getty Images

Among the numbers Ali called in the hours following the raid – and as soon as he arrived in Nairobi at the end of the first leg of his failed flight from justice – was one registered to a man investigators had come across before, in another Mombasa case, involving the Akasha network, a crime family allegedly run by two brothers, extradited to the US to face drugs smuggling charges earlier this year. For Peters and others, this was a crucial link.

While agents from the US Drugs Enforcement Administration (DEA) and Kenya’s Anti-Narcotics Unit were focused on the Akasha network’s alleged heroin operation, and a small group of determined Kenyan conservation groups, including Wildlife Direct, focused on the ivory trade, Peters worked to link the two. “Our investigation involved interviews with dozens of sources with knowledge about the Akasha network and ivory trafficking, including members of the crime community and law enforcement,” says Peters.

Then there were the phone records allegedly linking people involved in ivory seizures with the Akasha network, paper trails showing the shared ownership of trucking companies and vehicles, and shipping records that linked various ivory seizures to one another. “The work we do is very technical,” says Peters, “and most people would find it extraordinarily boring, but it is the piecing together of the little details to show how a criminal organisation moves containers through a port system and inevitably must leave a trace of their activities.”

Peters reckons she has so far connected 13 large ivory seizures since 2013 to the Akasha network, with a combined weight of around 30 tonnes. Given that authorities intercept only a fraction of smuggled ivory, the true figure is likely many times larger, meaning the Mombasa-based network may have been responsible for trafficking a large proportion of East Africa’s illegal ivory.

Meanwhile, as Peters was sifting through company documents, shipping paperwork and phone logs in Kenya and Washington DC, a biologist called Samuel Wasser, at Washington State University in Seattle, was coming to similar conclusions about the fundamental role in the ivory trade of a very small group of crime syndicates.

A container intercepted in Kenya in 2013 that was found to have ivory inside. Photograph: AFP/Getty Images

Back in the 1990s, Wasser devised a genetic map of Africa’s elephants using DNA samples that allows seized tusks to be traced back to their original populations, creating an overview of the ivory smuggling industry. More recently he began what he calls “sample matching” – seeking out pairs of tusks within ivory seizures – and found that more often than not an individual elephant’s tusks are split between different shipments.

“We identified a huge number of cases where the two tusks were in successive seizures, shipped through a common port, close in time, implying the same trafficker packed both shipments,” Wasser says. His research concluded that there may be as few as three major trafficking networks in Africa, running their operations out of Entebbe in Uganda, Lomé in Togo and Mombasa.

When Peters learned about Wasser’s work – published in the journal Science in July 2015 – she had a Eureka moment. “My eyes nearly popped out of my head because I realised he had come to the same conclusion as we had using a completely different methodological approach,” she says. “I tracked him down and we started comparing notes.”

In the case of the Mombasa network, Wasser has so far linked seven seizures of more than 1.5 tonnes since late 2011 and traced the vast majority of the ivory to East Africa.

Further evidence of the Akasha network’s involvement in wildlife crime was buried in piles of recordings made by DEA sources. Among the transcripts was one made on 25 April 2014, in which Ibrahim Akasha, the younger of the brothers, allegedly discusses selling ivory: “I have ivory here from Botswana, from Mozambique, from all over. I have a lot here and it sells,” he says, speaking in Arabic. “I have ivory, rhino horn.”

Members of the Akasha network in court in Mombasa. Photograph: Kevon Odit

It took more than two years to secure the extradition of Baktash and Ibrahim Akasha to the US. The arrests, at a smart villa in Mombasa’s upmarket Nyali neighbourhood on a Sunday evening in early November 2014, were the culmination of an eight-month investigation, but the subsequent extradition case went badly, thanks to a barrage of legal objections, serial absentee judges and an interpreter who refused to appear in court after receiving threats. Even in normal circumstances, Kenya’s courts are notoriously slow: on average it takes almost two years for a criminal case to be heard and there is a backlog of tens of thousands.

But, in late January this year and to the surprise of everyone involved, the Kenyan government suddenly intervened, permitting the immediate extradition of the Akasha brothers and their two co-accused.

“They’re like the mafia in the United States,” says DEA special agent Tommy Cindric, who led the Akasha investigation. “You have a family that is a criminal organisation, they’re not just into drugs, they’re multi-faceted and ivory is just one of their money-making products.”

When the court case begins in New York, likely next year, it is only the drugs charges that the four will face – the DEA chose to pursue an indictment solely related to their alleged narcotics trafficking - but Cindric says the linked investigation into wildlife crime played a part in forcing the extradition. “All the NGOs, Gretchen [Peters] and all the work they do on the ivory side was another facet of why it was important to get the extradition,” he says.

Gretchen Peters. Photograph: Paula Bronstein

Another US administration official said the ivory connection Peters made “helped elevate the consciousness of the Kenyan government to clear the judicial blockages”.

For Kahumbu, the revelation of the criminal linkages is fundamental. “The exposure of Ali’s links to the Akashas has pushed courts and police to take these cases more seriously,” she says. “It gives us a lot more confidence, in going after wildlife crime, to be able to say they are involved in other forms of criminality.”

There are other organisations attempting similar work. Satao, Drori and Eagle work across Africa; anti-trafficking group Freeland collaborates with Africa’s intergovernmental Lusaka Agreement Task Force; the Wildlife Justice Commission has had high-profile success against rhino horn smugglers in South Africa; and the PAMS Foundation worked with Tanzanian authorities to arrest Chinese national Yang Fenglan, the so-called “Ivory Queen” charged with smuggling more than 700 tusks from Tanzania to the far east. Sadly Wayne Lotter, co-founder of PAMS, was shot and killed by an unknown gunman earlier this week; it is not clear yet whether the attack was related to his work.

They have had some notable successes. Kahumbu says that after Ali was arrested “trafficking slowed down dramatically for some time” out of Mombasa. But the investigators are out-numbered and out-resourced by those they target, and their complicated, secretive and often dull detective work is hard to market to donors. So it remains a specialist, minority area of work. “The biggest challenge is getting these criminal actors put away. It’s very satisfying when it happens, but there’s a lot of frustration along the way and it can take a very long time,” says Peters.

The next step, she says, is a repositioning for Satao, away from a narrow focus on wildlife crime and towards corruption. That, after all, is the root of the problem. “The projects I’m planning for the future are almost all focussed on anti-corruption and not on fighting crime syndicates, because if you can get a clean system in place the crime syndicates can’t function. The elephant’s greatest threat is corruption, not poachers.”

Activist Ofir Drori. Photograph: Eagle