Tuesday August 4, 2015

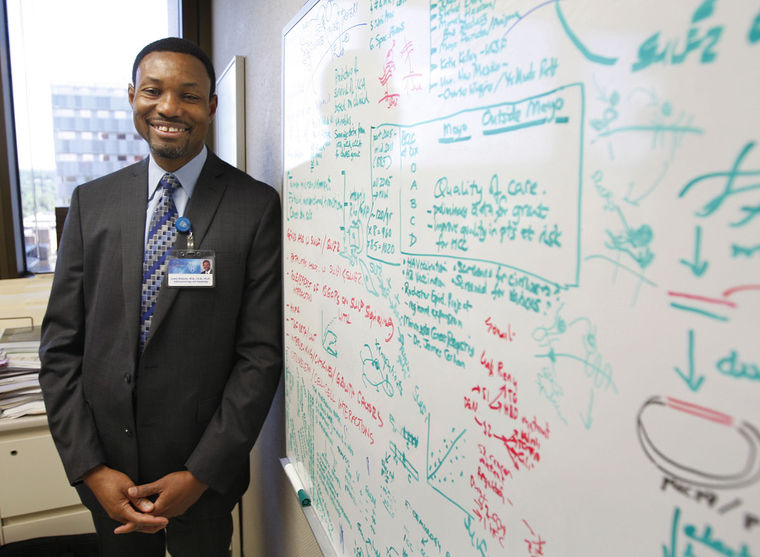

Dr. Lewis Roberts has been a driver behind a hepatitis testing and vaccination program within the Somali community.

A soccer championship halftime show isn't the most likely place to see a presentation on hepatitis awareness from a Mayo Clinic researcher, but one doctor's team is doing what it takes to get the message out to the local Somali community.Dr. Lewis Roberts' research shows that Somalis are much more likely to have certain types of hepatitis, which can lead to liver cancer. He wants them to get checked out before it's too late."A lot of people have no awareness, and they feel well. They don't realize they are ill until they reach the end stages of liver failure because of the liver's ability to regenerate itself and compensate. So by the time they begin to have symptoms, it is way too late to intervene and save the liver," said Roberts, a clinician and researcher in the gastroenterology and hepatology department at Mayo Clinic, said.

Roberts grew up and attended medical school in Ghana, and after coming to the United States for a Ph.D. program at the University of Iowa, decided to stay to pursue research opportunities since Ghana was in the middle of a recession.

He was accepted to the highly selectiveClinical and Translational Science program at Mayo Clinic, during which he received training to both practice as a clinician and do robust research work. After completing his training, he decided to specialize in treating and researching liver cancer because of its prevalence in Africa.

According to the American Cancer Society's 2008 counts, liver cancer is the leading cause of cancer deaths in men in Africa, and the third highest cause of cancer deaths in women after cervix and breast cancer. Roberts said this number may in reality be much higher, as many deaths may be attributed to other diseases of the liver due to incorrect diagnoses.

Once he started on staff, Roberts said he noticed that a disproportionate number of his patients were Somali. Several years later, Abdirashid Shire, who received an undergraduate degree in Somalia and a doctorate degree in London, came to Mayo Clinic in the clinical and translational program and began working with Roberts. Then, Somali community members began reaching out to Shire directly for help with liver cancer-related problems.

"That's when I began to think that there was more to this than face value, and that we needed to involve a community perspective," Roberts said.

After digging through medical records in an attempt to identify every Somali immigrant who had ever visited Mayo Clinic, Shire unearthed that Somali individuals were 10 times more likely than non-Somalis to have chronic hepatitis B and three times more likely to have hepatitis C. Both cause inflammation in the liver and are risk factors for developing liver cancer.

Hepatitis B can be sexually transmitted or passed on through different bodily fluids and from mother to child, while hepatitis C is transmitted through blood and needles. Genetics does play a role in the likelihood to develop chronic hepatitis versus the acute version, and these factors are part of Roberts' research.

Roberts said the environmental risks for the Somali immigrant population include blood transfusions, the use of needles, dental procedures, sharing razors within families, and traditional practices of circumcision and scarification if they were not practiced with properly sanitized instruments.

The risk of developing cancer from a chronic hepatitis infection can be reduced by early treatment, which can only occur if patients are properly screened and identified as having the virus.

"Clearly, the message is it's important to screen people to know the risk," Roberts said. "Screening and surveillance can find cancer at the earliest stage, and when we can do that, people's survival rates or much higher."

That led Roberts to collaborate in creating community health advisement committees to strategize in outreach to the Somali population in the area. That's where Shire's presentation at the soccer game comes in. The advisory committee organizes screening recruiting and education efforts including visiting faith organizations for screening, presenting at community events like the soccer game, visits to clinics in the Twin Cities and in Mankato, and educating school-age children about hepatitis.

So far, 700 Somalis have been screened. Around 15 percent of those screened tested positive for hepatitis B, and eight for hepatitis C. If the results are positive, they are referred to their primary care providers for further treatment.

The screening effort is currently funded in part by the Clinical and Translational Science program at Mayo Clinic and in part by Gilead Sciences, with funding to expand services to other immigrant communities from Kenya, Ethiopia, and Liberia and southeast Asian countries from Mayo Clinic's Office of Health Disparities Research (ODHR). However, Roberts pointed out that most insurance companies would cover the screening if health providers decided to administer it.

"We need to have recognition by health providers about individual risk since hepatitis is a major causes of illness and death in certain communities. We are just jump starting the process by doing free testing," Roberts said.