Friday, November 28, 2014

advertisements

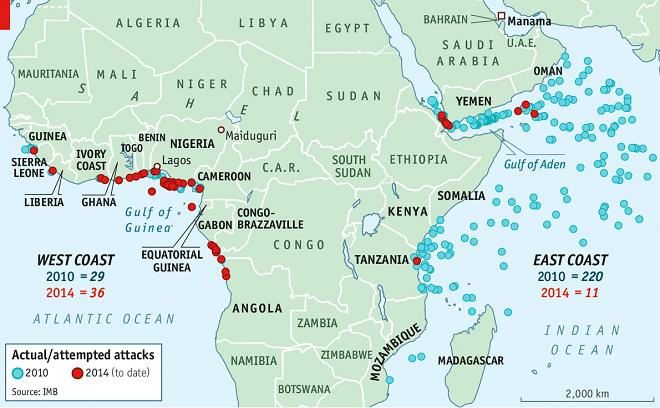

STICK-SLIM and still, Captain Lube sits in Lagos’s commercial fishing harbour, watching his crew clean a rusting shrimp trawler. He used to look forward to guiding them out to the rough Atlantic waters. But nowadays he has grown too afraid to venture far from the coast. Pirates infest west Africa’s seas, and he has seen many fellow captains kidnapped and sometimes killed. He has become jumpy; every approaching vessel might pose a danger. The trawling company for which he works says that attacks last year were “too many to count”.Just a few years ago the most dangerous waters in the world were off the coast of Somalia. But piracy there has fallen dramatically. It is more than two years since Somali pirates last successfully boarded a ship. At their peak in 2011, attacks were taking place almost daily. The number of attempts has fallen to a handful every month. Now it is the Gulf of Guinea that is the worst piracy hotspot, accounting for 19% of attacks worldwide, as recorded by the International Maritime Bureau. It registers an attack nearly every week (see map). The numbers are probably underestimates. America’s Office of Naval Intelligence reckons the real figure is more than twice as large—and growing.

The nature of piracy is quite different on the two sides of the continent. Around the Horn of Africa in the east, Somali pirates seek to seize ships and crews for ransom, and have ventured deep into the Indian Ocean. In the Gulf of Guinea in the west, attackers are more intent on stealing cash and cargoes of fuel, such as diesel, from ships coming in to port. Crews are sometimes kidnapped.

It is a quicker hit than the Somali hostage-taking. It also tends to be more violent because the attackers have little incentive to keep the crews safe. Armed resistance is often met with heavy machine guns and military tactics, says Haakon Svane, of the Norwegian shipowners’ association. Ships are seized for a few days, anchored quietly and cargoes are siphoned off into smaller vessels. The gangs also appear to have good intelligence, security sources say: they often know which ships to attack and they recruit the skilled crewmen needed to operate the equipment.

Frequently the targets are themselves involved in regional smuggling, so they switch off transponders or assume false identities, making it hard for rudimentary anti-piracy forces to keep track of them. Moreover, they do not report attacks.

Incidents have stretched all the way from the Ivory Coast to Angola, but the root of the problem lies in Nigeria. Most acts of piracy are committed in Nigerian seas, by Nigerian criminals. The trouble at sea is ultimately tied to the country’s dysfunctional oil industry and the violent politics of the Niger Delta, where most of the oil is produced. Nigeria is the world’s eighth-largest oil producer; nevertheless, it suffers from shortages of refined fuels.

Widespread “bunkering” (the term Nigerians use for the theft of oil) and a violent insurgency created the conditions for piracy to flourish. Analysts say there tend to be spikes in both bunkering and maritime criminality before elections, which may mean that politicians are using illicit means to finance themselves. If so, expect pilfering to rise as Nigeria’s presidential vote nears in February. “The ransoms are used for the elections,” says Hans Tino Hansen, managing director of the Risk Intelligence consultancy. He points to a “feudal system” in which politicians protect pirates in return for a cut of their profits. An added problem is that elections may divert the attention of the security agencies.

Atalanta on the Atlantic?

Some of the smaller countries in the region have appealed for help from the world’s navies. The success of various task forces, including the European Union’s Operation Atalanta, in dealing with criminality off east Africa leads people to ask why they should not repeat the job off the west coast. After all, about 12% of Europe’s imported oil comes from west Africa.

But years of anti-piracy operations around the Horn of Africa have strained navies. On the plus side, they have led to unprecedented international co-operation: for the first time since the second world war all five permanent members of the UN Security Council have deployed forces on the same side. Among those guarding these sea-lanes are forces operating under national, EU and NATO commands as well as club-like structures such as the Combined Maritime Force (CMF), whose anti-piracy mission is headed by a New Zealander.

Against that, however, officers complain that their crews are missing training for what they see as their main mission of high-intensity warfare. In addition, ships operating around Somalia wear out more quickly than those in other waters—dust and sand in the air damage their engines and the high temperatures harm electronics designed to operate in cooler Atlantic or Mediterranean waters.

Hence the NATO component of the anti-piracy force, which usually comprises four or five ships, is down to two—and securing these was a stretch. The EU force, which was meant to have disbanded this year, will now keep going until 2016. It is currently commanded from the decks of an Italian destroyer, the Andrea Doria.

Western countries are reluctant to get sucked into another commitment on Africa’s western coast. One reason is that attacks take place in territorial waters, where they count as “armed robbery at sea”. Dealing with them is the job of littoral states, not foreign navies (in Somalia, a failed state, UN resolutions authorised force in the country’s waters and on land).

Another is that, despite the oil, sea traffic around west Africa is small compared with the arteries connecting Europe and Asia through the Suez Canal. And although piracy in the east has been subdued for the time being, nobody thinks the problem will end until stable government is restored to Somalia. Indeed, the threat of resurgence may be growing given the thinning numbers of warships and the money-saving risks that shipowners are starting to take (sailing closer to Somalia, at slower speed and with fewer armed guards).

In short, nobody wants to become bogged down in another open-ended naval operation. The success around the Horn of Africa was because of a mixture of factors—intense patrolling by international navies, the deployment of armed guards on ships and defensive action by crews. It may be harder to reproduce that combination in the Gulf of Guinea.

In the narrow Gulf of Aden, for instance, ships were encouraged to sail fast and in convoys to make it harder for pirates to board; passive defences (such as bullet-proof rooms) and guards could buy enough time for warships nearby to come to the rescue. But in west Africa the most vulnerable ships are either at anchor or are lining up to come in and out of port. Nigeria has refused to allow ships to bring armed guards into its waters. Some that have tried have had their crews arrested and charged with arms smuggling.

West African states are trying to strengthen their coast guards with Western help, and efforts are being made to share information on shipping and attacks. But if there is to be a halt to piracy Nigeria will have to take the lead in patrolling its own waters and curbing illegal activity. Given the country’s inability to deal with an insurgency by Boko Haram militants in the north—a double suicide-bombing this week killed scores of people in the town of Maiduguri—there is little reason to think that it will have much success in protecting its waters. The worry is that piracy, itself, is becoming enmeshed with drugs- and arms-smuggling networks linked to violent jihadist groups in the Sahel.