By Robyn Dixon

Monday, September 17, 2012

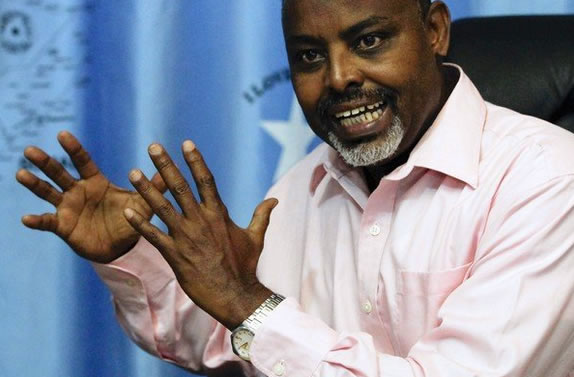

Mogadishu Mayor Mohamed Ahmed Noor looks at threats and an assassination attempt in a different way: They mean he is effective.

MOGADISHU, Somalia — The great part about being mayor of Mogadishu is that you get to reinvent a city so thoroughly taken apart by more than 20 years of chaos and war, it's almost a clean slate.

The hard part: staying alive. Death threats come with the job.

Outside Mohamed Ahmed Noor's office there's a huge sign, "Welcome to Mogadishu." At his entry sits a guard with a machine gun, looped several times with ropes of ammunition.

To get inside, you must squeeze through a hubbub of waiting people so dense you wonder how he gets any work done.

Some are waiting to ask him for jobs for themselves or their children or nephews. Some have no food to give their children. Many are caught up in land disputes, as people, encouraged by a year of relative peace, move back to their houses and property, only to find others have taken them over.

One of those who has come to see the mayor is an old friend from the Somali diaspora who used to play on the same basketball team in Mogadishu, in the good old days, before things went south in 1991.

Noor politely brings a meeting with a large group of men to a close. They stand and troop out.

"They're the district commissioners," he says.

He works with them every day, as do foreign aid agencies. But analysts say many of the district commissioners in Mogadishu are actually warlords with substantial militias, raising fears of a reprise of the terrifying years from the early 1990s until 2006, when warlords divided Mogadishu block by block with roadblocks manned by trigger-happy militiamen.

The mayor, 57, sits behind a modest desk, wearing a black shirt and a trim gray goatee. On his wall are five pen-and-ink drawings of the city. They don't depict the destruction left by two decades of fighting, but an idealized Mogadishu, like something out of a child's storybook, the perspective slightly off.

Noor brims with restless energy, and although his aide (a Somali American from Texas) warns the mayor hasn't much time available for the interview, once he starts, Noor sweeps on exuberantly for almost an hour, regardless of the clock.

After nearly a year of relative peace, Noor brushes aside fears the city could plunge back into conflict. He's concentrating on small things that he hopes will make a big difference: lighting neighborhoods to improve security, fixing roads, cleaning streets and markets and creating the kind of environment that he hopes will encourage businesses to move in, and people to move around more freely.

"I knew if we light [areas] it would reduce fear. I knew if we reduced garbage, it would attract people. I knew if we increased security, people would stay out later at night."

He's introduced traffic police, and has plans for traffic lights and street names.

In days gone by, Mogadishu "was dark, there was fear. It was filthy." And now: "There are high expectations. The markets are full. [The city] is full of opportunity."

Noor ran an Internet cafe and two community organizations providing services to Somali people in London as an emigre. He took part in the upgrading of London's King's Cross, formerly a seedy district, and he sees that as a model to change Mogadishu.

But it's not easy: In Mogadishu's case, funds are scarce.

"We're starting from a Hiroshima city. Where can we start? Where are the resources?" Noor says. "We have to move slowly, like a tortoise."

When he took the job, the Al Qaeda-linked Shabab militant group still ruled the city, and Noor knew it would be dangerous. There have been many death threats. When he moves around the city, he has a hefty security outfit. In August 2011, he survived an assassination attempt, possibly by the Shabab, when attackers blew up his car. He was not in it.

He has a determinedly rose-colored view of the attack.

"It encouraged me, because I was only the mayor. I wasn't the president or the prime minister or a general organizing the military offensive. I was just a mayor who decided to provide services. I said, 'What did I do to become a target? — it's because I'm doing a good job.' It heartened me."