'Rain in a Dry Land' documentary follows Somali refugees as they begin new lives in United States

By MICHAEL LONG, Entertainment editor

Sunday, September 02, 2007

|

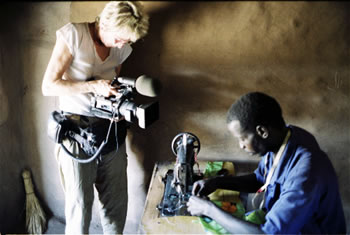

| Cinematographer Joan Churchill films Abdulkadir Ali Yunye as he works at a refugee camp in Kakuma, Kenya. The scene is among the 300 hours of footage that generated "Rain in a Dry Land," a documentary about displaced Somalis. |

Years of pouring her time, emotions and capital into "Rain in a Dry Land," a thoughtful account of two Somali refugee families who relocate to the United States, had crystallized into less than an hour and a half of celluloid.

The film, which earlier this summer opened the 20th anniversary season of the PBS "P.O.V." documentary series, has a back story as compelling as the finished product.

In March 2003, Makepeace read an article in the New York Times about a cultural-orientation class for Somali Bantu refugees. The group of ethnic Africans consisted of illiterate subsistence farmers who had been driven from their fertile homeland and were living in a refugee camp in Kakuma,

advertisements

Kenya. They were Moslems, and the thought of thousands of these refugees relocating to a post-Sept. 11 America captivated Makepeace."It's the stories that just take you by storm and sweep you away that you feel you have to do. You sweat blood for them," Makepeace said in a telephone interview from her home in Lakeville, Conn. "I'm very happy with the way this film turned out and with all the serendipitous things that made it work."

"Serendipity" is a kind term to describe the problems and occasionally harrowing events that shaped this film.

First, Makepeace spent eight months "diplomatically harassing" the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees and the International Organization of Migration, which organized the orientation classes and arranged for the refugees to travel to America. Winning the support of these organizations was the key to moving forward, she said.

Once Makepeace was inside the country, the language proved a formidable task. She unwittingly hired a translator who had made bitter enemies among the people she wanted to film (think death threats) before she employed the head of a literacy program who was himself a Somali Bantu and a trusted member of the community.

When shooting scenes in the literacy classroom, the translator would sit in a separate room with headphones and a microphone, translating for the cinematographers as the teacher introduced his charges to exotic appliances, such as a refrigerator and stove, and informed them of cultural differences. For instance, in America, he said, men are not permitted to force women to have sex.

Makepeace and her crew also had to contend with 6 p.m. curfews at the U.N. compound where they were staying (it's not safe to venture out after dark) and a general lack of simple technology on location (lights, for instance).

During the year and a half of shooting the refugees in their American homes, she often found herself without a translator, "shooting from the gut."

"We would just keep shooting and try to sense what was dramatic, and we didn't find out what was going on until months later," she recalled. "I was fortunate, through the network of people I got to know who work in refugee resettlement, to find a guy in Boston — he's Somali, not Bantu, but he had grown up near the Bantu, so he knew the dialect really well — and he was a brilliant man, fluent in English."

At first, she just sent her Boston translator footage that had been shot stateside, but after hearing the nuances he uncovered in the Bantu dialect, she had him retranslate the footage shot in Africa. Suddenly, observations such as "When I get to America, I will take my children to school" became "When my eyes and ears arrive at a place where the breeze is blowing, I will take my children to school."

"Talk about lost in translation," Makepeace said.

Documentary films have long been the chosen format for rooting out basic humanity, and by poring over footage and parsing translations, filmmakers uncover the most luminous elements of their stories.

"You're bringing into the foreground the most moving, most compelling moments that move the story forward," Makepeace said. "You have to have the material there in the first place, but it is an artful arrangement of that material that makes or breaks the film."

When she considers what she wants people to take away from "Rain in a Dry Land," Makepeace thinks about a shot at the end of the film: The camera pulls in tight on Arbai, a female refugee. Close up, it's hard to tell what she's doing. Then the camera pulls back to reveal the vast warehouse in which Arbai is operating a floor-scrubbing machine. She is an American janitor.

Makepeace, who won an Emmy for her cinematic portrait of famed war photographer Robert Capa, hopes "Rain in a Dry Land" will change people's attitudes toward immigrants and refugees and encourage tolerance in communities and in the halls of government.

"[I hope] when we see immigrants, whether African or Hispanic or whatever, doing these kinds of jobs that have generally been invisible to most of us, that they will become visible in our midst," she said. "And that when people see them, they'll realize that there's a whole incredible story behind them, of suffering, loss, resilience, courage and hope and the success of bringing their families to safety."

Ephrata Public Library, 550 S. Reading Road, will show "Rain in a Dry Land" at 7 p.m. Monday, Sept. 10, as part of the Reality @ Your Library documentary film series. For more information, call 738-9291 or visit www.ephratapubliclibrary.org.

Source: Lancaster Online, Sept 02, 2007