Thursday, January 24, 2013

By Hassan Muse

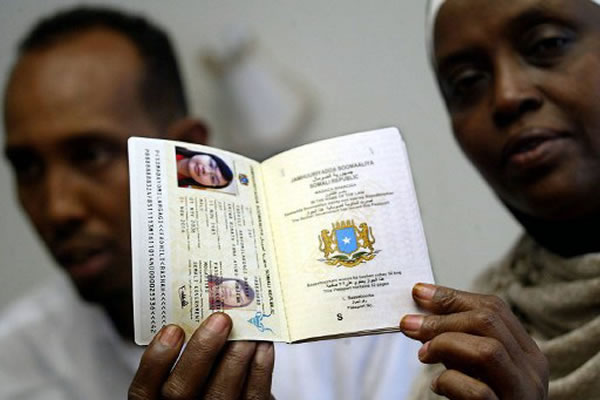

Officials from Somalia's Transitional Federal Government show a copy of the country's biometric passport in November 2006. The state-of-the-art passport replaced the older document that was easier to forge. [Tony Karumba/AFP]

Hassan Mohamed Jama, 53, has made a living as a counterfeiter in Bosaso and Garowe for the past 20 years.

He makes the old green passports used under the previous regime, red diplomatic passports, university diplomas, birth certificates and property deeds. Jama, who still works in the trade, said that without the forged documents life would have been difficult for many Somalis.

"When we were starting this work, the country did not have a place for people to obtain documents and Somalis were traveling every day because they were receiving scholarships," Jama told Sabahi. "We were serving as the local government and the Ministry of Education, we filled all those gaps."

"We make the old green passports for up to $100. We charge $300 to make university certificates such as one for the Somali National University, even though it is hard to procure the original stationery. Certificates for universities that were created after the collapse of the country cost $60," he said.

Even though the old passports and school diplomas are no longer officially recognised as valid by the federal government and regional administrations, people still depend on counterfeit documents. Jama said he sees about 20 people every day who want forged certificates and the old green passport, which can be used to travel to some countries that do not enforce the ban.

"People are used to our services that enable them to obtain a passport, a university certificate or a high school certificate within 20 minutes," he said. "That is what they find indispensable and we are dependent on it to provide for our children."

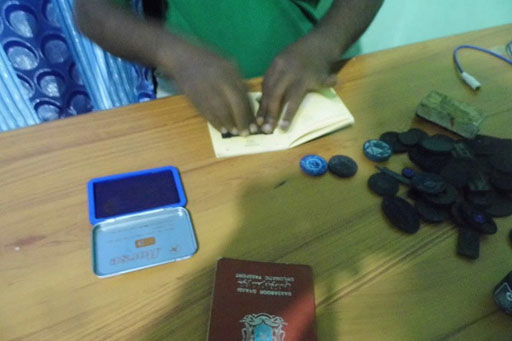

He said Somali forgers have all the stamps used by previous government agencies, and utilise many of the signatures of former government officials which has created confusion in foreign countries.

"We were forced to learn how to forge those signatures to produce documents that look legitimate because many countries around the world kept the signatures of government officials on file [to verify]," Jama said.

Hassan Mohamed Jama stamps counterfeited Somali passports using materials stolen from government offices after the central government collapsed in 1991. [Hassan Muse Hussein/Sabahi]

Steps to prevent forgery

Although the forgery system has flourished in Somalia for over two decades, there are some indications that the government is taking steps to combat the problem.

For one, Somalia's Transitional Federal Government created a new biometric passport in 2006 and changed the colour to blue. The government set up a passport printing facility in Mogadishu in 2010, moving it from the United Arab Emirates, to expedite passport delivery services.

In 2011, the government officially outlawed the use of the old green passports for international travel or business activities, however some countries do not enforce it.

"The forgery perpetrators were obstacles to the country's [progress] by creating a bad reputation for the country's passport," said Ali Abdi, an official at the federal passport bureau in Galkayo. "They were found making passports for foreigners in the markets."

"The federal government has now asked other countries worldwide to reject the former Somali passport and to accept the new one," he told Sabahi. "This change is visible because every day we register about 100 people seeking the new passport."

In 2010, the Puntland regional Ministry of Education also instituted a programme to prevent forgery of its university diplomas, the ministry's director of training Ali Farah told Sabahi.

He said the ministry has contracted a company in Malaysia to create diplomas printed on special paper with security marks in the middle that cannot be forged. The diplomas were forwarded to all the local universities and countries in the region where Somali students seek scholarships to further their education, he said.

"We decided to do that after we saw our diplomas being fabricated domestically and were even forged in Sudan," Farah said. "We decided to combat the problem and we even refused to announce the company that made [the new diplomas] to prevent contact with them that might lead to further forgery."

"In 2012 we found out that forgery incidents in the country have gone down according to local universities that worked with us to combat the problem," he said.

Demand for forgery must be eliminated

"During the chaotic period, [the forgers] provided services the government used to provide for people. People would have been lost if the services were not available," said Abdi Abdullahi Sheikh, a 24-year-old Garowe resident who attends Gambol High School.

"For example, passports were easily obtainable without many problems or travel delays," he told Sabahi. "They facilitated the number of Somalis that have travelled around the world for trade and education in the past 20 years."

It is difficult for the government to fully combat the forgery business that has been going on for over 20 years, said Garowe-based political analyst Saleban Jama. The government can change the culture and make Somalis understand that is it time to move beyond forgery, he said, but it has to provide an alternative.

"For example, birth certificates, marriage licenses, driving licenses and all those things are not issued in Mogadishu currently," Jama told Sabahi. "Therefore, anyone who needs them or is required to have them to travel abroad gets them from the [forgers]. The government has to fill that role because forgery sprung from demand [for services] and if they are provided, then people will not want forgery."