Saturday, December 08, 2012

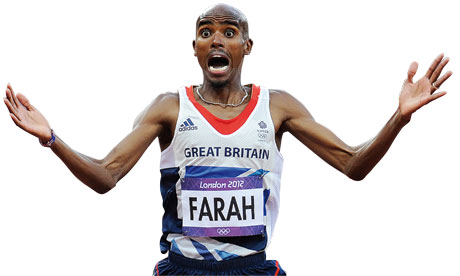

Mo Farah: 'I said to myself, I don't want to be coming sixth or seventh, and being the best in Britain. I want to be the best in the world and race against these Kenyan guys.' Photograph: Harry Borden for the Guardian

Once, he spent time playing computer games and eating curry. So how did Mo Farah become a man driven enough to win double gold at the Olympics?

Mo Farah is strolling around the lush grounds of a Middlesex hotel. His huge eyes are darting everywhere. He spots potential locations for the pictures, tells us he used to be a photographer himself, admits it might be a bit of an exaggeration but he was given a camera to document the 2008 Beijing Olympics, wants to know about the people I've interviewed, asks if it's true Stevie Wonder could have got his sight back but didn't want to. Then he stops. He's jumping up and down outside a glass-fronted cafe, banging on the window, grinning, making a strange gesture with his hands.

Farah is actually Moboting to catch somebody's attention. It's as if he's convinced nobody will recognise him unless he pulls his signature pose, hands on head to form an M. Andrew Triggs Hodge, Olympic gold medallist in the coxless fours, runs out of the cafe to meet Farah, who Mobots again just to make doubly sure Hodge knows it's him.

Farah and Hodge have just competed in the Superstars Christmas special, that great test of sporting strength and versatility.

Farah: "You well, mate? You recovered?"

Hodge: "Mate, I'm in pieces. My quads… I'm still completely in awe of your javelin, mate."

I look at Farah, all skin and bones. Can he really be a good javelin thrower?

"This guy is a monster. Absolute monster," Hodge says. He turns to Farah. "If you're doing anything fun, give me a shout. I never do anything fun, so I'll just come to your fun stuff. Hahaha!"

There are many wonderful images to take from London 2012, but perhaps none quite as inspiring or visual as Mo Farah in his moments of glory. There he is, surging ahead on the final lap of the 10,000m on Super Saturday, driven by the loudest chant I have ever heard: "Mo, Mo, Mo." There he is, eyes on stalks, as he realises he's won. There's his daughter Rihanna running on to the track, Mo sweeping her into his arms and throwing her into the air. There's Mo kissing the ground, Mo slapping his head in wonder, Mo kissing his wife Tania and dedicating his two gold medals to the twins she was carrying. Even events that had nothing to do with Farah were tinged with his golden glow: Usain Bolt celebrated breaking the world record in the 4x100m relay by doing the Mobot as he crossed the finishing line.

It is impossible to overstate Farah's achievement in winning double gold in the 5,000m and 10,000m. No Brit had ever done it. Ethiopians had won the 10,000m at the past four Olympics, and until recently Farah's best was two minutes slower than the great Kenenisa Bekele's world record of 26 minutes and 17 seconds. He is the first Brit to win Olympic gold at 10,000m, the first to win gold at 5,000m in world or Olympic championships, and on it goes. By the end of the Olympics, Farah was cited as the symbol of a newly proud and inclusive nation – the Somali-born Muslim who grew up in London, trains in Kenya, lives in America and represents the best of modern Britain.

The most astonishing thing about Farah's story, though, is just how far he has come. When he was English schoolboy champion, nobody believed he'd go on to be English champion. When he made it to that level, nobody believed he'd go on to be the best in Europe. And when he won double gold in Barcelona in 2010, nobody dared dream, let alone believe, he could go on to repeat it at the Olympics.

Farah, 29, was born in Somalia and moved to Britain when he was a young boy. There are numerous stories about his early life, many of them untrue. "It's like Chinese whispers," Farah says. The most common myth is that he came as an asylum seeker. In fact, his father Muktar was born in Hounslow and went to work as an IT consultant in Mogadishu, where he met his wife Amran. They lived in a big stone house, had six children and, when civil war tore Somalia apart, Amran and the children moved to neighbouring Djibouti, while Muktar returned to London. When Mo was eight, he and two siblings moved with their mother to England, to be with their father. Three children, including his twin brother Hassan, were left with their grandmother in Somalia, because Muktar couldn't afford to bring them all. The twins didn't see each other for 12 years.

Farah winning the 5,000m final: 'Yeah, it's definitely sunk in. It's over now. Done. On to the next thing. Move on.' Photograph: Tom Jenkins

Has Farah ever wondered how life might have turned out if he had stayed in Somalia and Hassan had come here? He shrugs. "All my life, pretty much, I've lived here. I don't know any different. Hassan has lived all his life in Somalia, so for him it's different." He and Hassan, a mechanic, are now in regular contact, and Mo visited him last year. Is he a good runner? "No, he's rubbish!"

Farah remembers little about the early years – just running up and down the streets, kicking a ball. In a way, he says, life began when he moved to London. After years away from his father, he was thrilled when they were reunited: "Seeing Dad was more exciting than anything else."

Farah couldn't speak English when he arrived. The first words he uttered in the playground were, "Come on, then." He doesn't know where he got the expression from, but he remembers the black eye the hardest kid in school gave him. "This lad kicked a ball away and I went, 'Come on then' and that was that." Did he ever say it again? He grins. "Yeah, I said it to everyone." Was he tough? "I wasn't a fighting kid or a causing-trouble kid. I was just one of those cheeky, crazy kids running around." You can still see that mad energy today.

Farah, an Arsenal fan, was desperate to be a footballer. As a boy, he didn't care much for running, and his PE teacher and mentor, Alan Watkinson, had to bribe him to compete on the track. "The only way he could get me going would be to say, come half an hour early and I'll let you have a kick-about." Watkinson has been a huge influence on Farah's career, and was best man at his wedding. You need somebody who believes in you, Farah says, somebody who'll make sacrifices and push you. Watkinson has always been there for him, as has Paula Radcliffe, not only supporting his running but also funding driving lessons so he could get to training independently.

When Farah talks about his career, the same words come up again and again: discipline, sacrifice, graft, pain, selfishness. He seems the ultimate example of the uncompromising athlete. But, he says, it used to be so different. Even when he was studying athletics at St Mary's University, what he really wanted to do was muck about. "I was one of the lads, having a good laugh, doing what normal 18-year-old boys do." Such as? Well, there was the time he jumped off Kingston bridge naked. Why did he do it? "Because I was mad when I was younger. I just had too much energy."

Was he drunk? Course not, he says – he's a good Muslim. "No. I was with my mates and if somebody dared you, you'd do it, wouldn't you?" He looks at me, a pleading tone in his voice. "At that age?" Was there anyone around? "Yeah!" Any police? "Well, somebody shouted, 'Police' and I had to leg it down the street and hide in the bushes." That footage would be worth a fair bit today, I say. "Ha! I don't know if I want to see that, to be honest."

For a long time, Farah says, he didn't push himself enough. In 2005, aged 22, he moved into a house in London with the Australian runner Craig Mottram and a group of Kenyan runners, including the 10,000m world number one Micah Kogo. Farah had already come second in the European under-23 championships and run for Great Britain, so he was no slouch. But watching Mottram and the Kenyans made him feel like one. "They were sleeping, eating and training, sleeping, eating and training. And I said to myself, if I'm ever going to have any chance of beating these guys, I'm going to have to change something."

How was his lifestyle different? "I was out with the boys, playing computer games, going out for a curry. I thought as long as I run, that's it. I didn't know any better." Did they say anything to him? "No, but they'd try to wake me at 6am and I'd say 'OK, OK' then just go back to sleep."

So what changed? Farah says he just got fed up with himself, and with settling for relative success. "I said to myself, I don't want to be coming sixth or seventh, and being the best in Britain. I want to be the best in the world and race against these Kenyan guys." They invited him to train with them in Kenya, and while he was there he did get up at 6am and follow their routine. In 2006, he won the European cross-country championships. Then he had to step up another gear. So he spent more time in Kenya, running at altitude, building up speed and stamina, eating sensibly, resting and sleeping.

In 2008 he got together with Tania. They had met at school in west London, when Farah was 12, and her first memory of him is as a little boy with a bleached-blond afro. They went to the same athletics club and lived round the corner from each other in Hounslow; Farah was initially friends with her brother. When they became a couple, Tania had a daughter, Rihanna, who was two.

By now, Farah was training for months on end, away from Tania. He was clear in his head, and made it clear to her, that running had to come first. In 2010, they married and went on honeymoon to Zanzibar. When they were due to return, the ash cloud erupted and their flight was indefinitely delayed. Farah turned to his new wife and said he would have to leave her, to resume training in Kenya. She'd have to make her own way home.

Bloody hell, I say. "Well, I hadn't trained for a week," he says as if it's a no-brainer. So what did he say to Tania? "I'm like, 'We've already had our honeymoon, we've had time to rest. I've got to get back training.' Then I just left her in Nairobi."

Was that a hard thing to do? "It wasn't an easy decision. We'd just got married. The sort of person she is, she understood. She didn't like it…" He pauses, struggling to explain. "Would you do that?" For a work deadline? You're joking. His agent, Mike Skinner, a former 10,000m runner for Great Britain, is listening. I ask if he'd leave a honeymoon to train. He laughs. "No. That's the difference between us and these guys who get there."

Farah spent six weeks in Kenya. Did he phone home every night to apologise? He grins. "Yeah, I rang up and went, 'I just called…'" and breaks into Stevie Wonder's I Just Called To Say I Love You. What mood was Tania in when he got home? "She was excited to see me. Then I won double gold at the Europeans, so it was like, yeah, it was worth it."

Actually, Skinner says, a better example of his uncompromising approach came a few months later, when Farah decided he needed a new coach. "When Mo won the European double in Barcelona in 2010, he was riding the crest of a wave, but in his own mind he thought he was 1% or 2% away from how good he could be. So he decided to move everyone from London to Portland, Oregon, to train with Alberto Salazar. It wasn't as if somebody said, go to Portland and you'll win Olympic gold."

"Yeah," Farah says, "it wasn't a guarantee."

Was that an easy conversation to have with Tania? "That was one of the hardest." Harder than the honeymoon? "Yeah, because there's a kid involved and you're changing her school. Everything she knew was taken away from her. Her friends, her nanny. She was five." Did she resent him for it? "No. You have to make it exciting for her; it's how you sell it to her. But at the same time she had no choice." Would the younger Mo have made such ruthless decisions? "No. No. No."

In America, Salazar introduced him to radical training methods such as underwater treadmills and cryogenic chambers. He worked on his upper body strength and eradicated a tendency towards bobbing arms. After 18 months in America he returned for the Olympics and, on 4 August 2012, he concluded the greatest night British athletics has ever seen with victory in the 10,000m. That was when he knew it had all been worthwhile. "There's a time in everyone's career where you go, 'Ah, this is hard – how long am I going to have to do this?' But the rewards are so great. Who gets to go on the podium and hear the national anthem? The whole nation singing! Money can't buy you that." A week later he ran himself into the record books, winning the 5,000m.

I mention that, a few weeks ago, Bradley Wiggins told me his Tour de France victory will never sink in. Farah looks baffled. "Why not?" His victory has sunk in all right. Sure, he couldn't sleep the night of Super Saturday. He tossed and turned. He looked at the gold medal he'd just won and asked himself if it had really happened. But that was a long time ago. "Yeah, it's definitely sunk in. It's over now. Done. On to the next thing. Move on."

Many athletes say that, after winning an Olympic medal, there is an anticlimax. Farah says it's inevitable, especially in his case. "It can't get any better than that, can it? You've done it. You've still got to train as hard, but that cannot be topped." Now, he says, he has to remotivate himself. "You've got to forget about it, focus on something new. Learn to be the best – as well as dealing with the pressure." His immediate target is the world championships. "I can't afford to go, 'I'm an Olympic champion, I'm all right, I can lie back.'"

It's been suggested his next challenge will be the marathon. He nods. "I'd like to see myself doing that." Maybe he'll do the marathon in Rio 2016? "No, I'll be running it before that. You've got to train hard. The Kenyans train hard all the time."

He's not exactly been taking it easy since the Olympics. A few days after winning his second gold, Tania gave birth to twin girls, Amani and Aisha. With his new-found celebrity, the births were splashed across the front pages of Hello! magazine and the twins were on breakfast telly within weeks. How are they coping? "It's tough," he says, "changing nappies, getting involved." And there are bound to be times he's not there for them. "Sometimes the family has a problem and you have to block it out. If your kid's sick, are you going to get a flight back from Kenya? You have to know your wife is taking care of them, but at the same time concentrate on the training."

In the few weeks he's been back in the UK, he's made a Mobot dance record he'd love to see top the Christmas charts, competed in Superstars, worked with his foundation to provide clean water in Africa, and is now campaigning to win Sports Personality of the Year. He says he's having a great time, but you sense he can't wait to get back to the peace of America. "It's a lot easier than being here. Training, and nothing to worry about."

As we leave, I see what he means. We walk out and somebody shouts, "Mo!" In seconds there's a swarm of fans around him. They all say the same thing: "I never normally ask for autographs, but you're different – just one picture, one Mobot."

As the crowds disperse, I find myself trying to explain just how much he means to us; how his victories were rare moments of pure, ecstatic emotion; how many of us still feel a surge when we think back to those August days. Does he? "Yes, I get emotional. Course I do. It was amazing. I'm never going to experience anything like that again." Now you can really see what it means to him. His sentences come out in a rush, and suddenly he's not even talking about his victory, but the moment Usain Bolt celebrated his own win with a Mobot. "He did that for me as he was breaking the world record. When's somebody ever going to do that again breaking a world record?" Never, I say. "Exactly," he says. "Never."